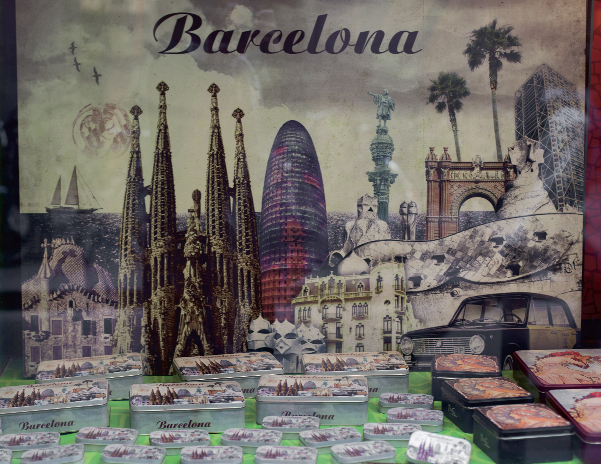

Photo: Camilla de Maffei.

The window of a patisserie on Carrer Princesa, with Barcelona souvenirs and merchandising.

Barcelona is currently the scene of a battle between its exportable symbols, the ones that make it a consumer product, and its communitarian symbols, which are threatened with extinction due to from the impact of tourism. A colonial past and international image also play a part in the debate.

This battle is a place where the iconographic symbols that make up the image of the city and give it its symbolic identity live, multiply, die and come back to life. Some of these symbols, the ones that suit the official discourse of the day, are obvious and extraordinary: those that show up on postcards, t-shirts and selfies, recognisable the world over. But then there are other more silent and conventional symbols that are woven into daily life and reveal the different ways in which Barcelonians make the city their own.

On Sunday 21 February 2016, Mark Zuckerberg uploaded a series of photographs on his social media pages while going for a run in Barcelona. “Good morning, Barcelona! We kicked off our visit with a run around the city, from La Sagrada Familia up to Castillo de Montjuïc. Best way to see a city before meeting with partners on our journey to connect the world”, he wrote. In between jokey comments about whether he was visiting the city “because of the ham” or the Mobile World Congress, he made public (and viral) a 16 km route that took him around picture postcard Barcelona, the city that is seen – and sold – in souvenir shops and on TripAdvisor.

Zuckerberg’s run got more than 421,000 likes from his 61 million Facebook followers. All the locally-sold newspapers (El País, La Vanguardia, El Periódico de Catalunya, Ara, El Mundo, El Punt Avui, Vilaweb) ran the story on their websites or in print the following day. What do Zuckerberg fans around the world see in the backdrop to this young American’s route, and what are they looking at? How do Barcelonians themselves see and look at this backdrop? And, above all, why did Zuckerberg use the verb to see?

Nowadays visitors recognise cities before they have even visited them, and when they do experience them they broadcast them as a series of selfies, visual captions written in the first person. These selfies, which are almost always uploaded on the Internet, differ only in the faces that appear in the foreground: a Japanese man, a Danish family, a group of French people. Everything behind them is always the same. Giandomenico Amendola, professor of Urban Sociology at the University of Florence and Director of CityLab, a multidisciplinary urban research centre, commented the following in La ciudad postmoderna (The Postmodern City): “We travel, attracted by these images of cities and places, often only to find in these experiences the confirmation of the familiar image and the opportunity to give an account of the city that has already been written.”

This symbol-filled narrative creates a scenario – partly political, partly private and partly the product of the local government marketing machine – that sets in stone a particular way of understanding the city and dilutes the vast range of narratives that could result from each person’s own experience.

Exportable symbols versus communitarian symbols

Photo: Camilla de Maffei.

The cat sculpture by Fernando Botero, a landmark of the Rambla del Raval, both a tourist sight and a meeting point for locals.

Barcelona is currently witnessing a struggle between its exportable symbols, the ones that make it a consumer product, and its communitarian symbols, which are threatened with extinction in a city whose neighbourhoods are undergoing gentrification. This battle is a place where the iconographic symbols that make up the image of the city and give it its symbolic identity live, multiply, die and come back to life.

Some of these symbols, the ones that suit the official discourse of the day, are obvious and extraordinary: those that show up printed on t-shirts, rulers, bags and posters and give a selfie or postcard-like reading of the city that is one-sided in nature.

On the revolving postcard racks at any stall on La Rambla the selfie backdrops, the official symbols, are on sale: La Sagrada Familia, the Collserola tower, the Agbar tower, the Calatrava tower, the Columbus monument and the Hotel Vela (all together, a nice skyline). To these we can add Park Güell, Montjuïc, Camp Nou and the Boqueria market. In the postcard-shop windows of the museum gift shops, the symbols change but they are still a series of separate, public and private objects that now make up the physical features of the slightly more “cultured” Barcelona: Rebecca Horn’s sculpture L’estel ferit (The wounded star) on the beach at sunset; the flower-patterned paving stone (one of the five winning designs in the competition held by the City Council in 1906 to decorate the pavements) as the sole subject of a postcard; the Hotel Vela once again, but this time as a Polaroid; Fernando Botero’s Gato (Cat) among the palm trees of the Rambla del Raval; Keith Haring’s graffiti at the Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art (MACBA).

These are isolated objects: L’estel ferit could be in Palma de Mallorca, but it is obvious (and well known) that it is in Barcelona. Haring’s mural is obviously on a wall of the MACBA, but no mention is ever made that it was once on a dirty wall in Plaça Salvador Seguí, in El Raval, and that Haring’s assistants were the lads of the Barrio Chino, some now dead because of the devastating effects of heroin in Barcelona in the 1990s.

To these hypervisible symbols that are official, exportable and recognisable the world over, we must add others that are more silent and conventional. The latter form such an intrinsic part of the identity of the city and its residents that they owe their existence to local residents and become visible when they disappear or are conquered by some official monument: the squares of Barcelona, the grid-like pattern of El Eixample, the taxis, the buses, the street names, the Pakistani hairdressers, the sandwich shop on Plaça Sant Jaume.

These are changing and fragile symbols, and they expire when they succumb to the trivialisation of the tourist industry and appear in guidebooks, on TripAdvisor, in low-cost airline magazines or on lists published in international magazines. They are also the social footprints of the different ways in which residents take ownership of their city. Marta Rizo, an academic at the Autonomous University of Mexico City, writes, in her Imágenes de la ciudad, comunicación y culturas urbanas (Images of the City, Communication and Urban Cultures): “The main virtue of a public space is that it is at once a space for representation and a space for socialisation, in other words, of the co-presence of citizens.”

From the intimate symbol to hypercommercialisation

We interviewed Álex Giménez, architect and lecturer at the Barcelona School of Architecture (ETSAB), near the Rambla del Raval, for which the current symbol is Botero’s Gato. In the fifteen minutes before the interview begins, the sculpture is photographed by nine tourists. Tariq and Mohammed, two local boys, like to use it as a slide, and the Gato is now a meeting point for Barcelonians the way Café Zurich on Plaça Catalunya was until ten years ago.

This enormous black solid feline arrived on the Rambla del Raval in 2003, having strayed around half of Barcelona; first, it lived in Ciutadella park; then, for the Olympics, it was moved next to the Olympic Stadium on Montjuïc; and, before coming to El Raval, it spent some time on a pedestal at Portal de Santa Madrona. When it came down to El Raval in 2003, the residents of this neighbourhood, despite the disappearance of several streets to make way for the Rambla, welcomed it with open arms and made it one of them: another neighbour. They socialised it.

Photo: Camilla de Maffei.

Plaça Reial is a paradigmatic urban symbol of a way of “making” a city based on understanding the needs of people, according to architect Álex Giménez.

That is how Álex Giménez explains how the city’s symbols have historically been born: “Barcelona is conceived on the basis of gaps. In the DNA of Catalan urban planning, even before the Cerdà plan, the empty space as a place of collective expression is extremely important, in all its dimensions. So its symbols journey from intimate beginnings to the street; they are built on an understanding of the most personal needs. Premodern Catalans had a great way of creating a city: for example the Plaça Reial, the Plaça de la la Boqueria.”

When it comes to the later evolution of this model, the ETSAB lecturer feels that “in the 1980s, the periphery of Barcelona was monumentalised, something that wasn’t being done anywhere else in the world. Quality was brought together with the formal appearance of various public spaces that democratised the city. What they were doing on Passeig de Gràcia was just as important as what was being done on Via Júlia”. But, he points out, “that rationale no longer exists; now we move from the general to the specific. Everyone is very concerned with building great collective symbols that ignore the needs of the people.” Giménez prefers “the city that is the sum of conventional things – because when you encounter it, extraordinary things happen – as opposed to a city made of a sequence of extraordinary things with gaps in between that are repetitive, sterile, tedious, expensive to maintain, unpopulated, depressing, unsubstantial and alienated”.

This sequence of extraordinary things is the iconic landmarks. But according to Giménez, it is precisely when the city decides to incorporate an iconic landmark as such that it stops working. He gives the example of La Sagrada Familia, which is in the wrong location for its size, making it incompatible with the surrounding buildings.

The hotel whose outline we can see during the interview and that is lit in fuchsia tones by night has not become a postcard, meeting point or tourist photo: it is not a symbol of Barcelona, neither for foreigners nor for locals.

Three phases in the production of symbols

Miquel de Moragas i Spà, Professor of Communication Theory, has just published a book entitled Barcelona, ciutat simbòlica (Barcelona, symbolic city). He claims that Barcelona has had three historical periods in which it produced a great number of symbols: the Universal Exposition of 1888, the International Exposition of 1929 and the Olympic Games of 1992. Moragas argues that the iconic landmarks of the three phases converse with each other and even create a mosaic of symbols that are hard to associate with any particular period. He gives as an example the monument to Columbus erected in 1888. “Who relates it to that date? Almost nobody”, he both asks and answers.

He explains that in 1888 European cities were desperate to become monumental, following in the footsteps of Paris (Josep Puig i Cadafalch wrote that Barcelona could become the “new Paris of the south”) and to give public recognition to the city elders as a form of urban propaganda. The monuments to Joan Güell, on Gran Via de les Corts Catalanes, and to Antonio López, at the end of Via Laietana, belong to this time and are the public representation of the hegemonic, political and economic power they both had.

In 1929 the monumentalisation of the city embodied a message somewhere in between the artistic movements of Catalan modernism and Noucentisme. It is at this time that depictions of nature and female bodies start to appear, albeit still in an abstract representation and the only sculpture bearing an actual woman’s name in the whole of Barcelona is the bust of the painter Pepita Teixidor, sculpted by Manuel Fuxà in 1917, which has remained in Ciutadella park ever since.

“The symbolic pieces of 1929 include the Magic Fountain of Montjuïc, although the Exposition of 1888 already had a magic fountain. The one from 1929 was built to promote the electricity industry, capitalising on the “look” of Montjuïc, a look that was to be reused in 1992”, explains Miquel de Moragas.

Photo: Sebastià Jordi Vidal / AFB.

Evening view of the site of the International Exposition of 1929, with the Avinguda de la Reina Maria Cristina illuminated and the Magic Foundation, in a photograph from the exposition album.

Photo: Fundació Barcelona Olímpica / Barcelona City Council.

The Olympic Stadium on Montjuïc during the opening ceremony of the Games in 1992.

The third era of symbol production was the Olympic era, which was to give rise to what is known as the Barcelona Brand. “The 1992 period”, reflects Moragas, “witnessed the defence of the public space”, and it was that abstract symbolism that emerged in the Cultural Olympiad. Then came the Forum of Cultures phase in 2004, with the building of the 22@ technology district. Moragas characterises that period as one of “commercialisation of the city”, which led to the citizens’ rejection of the system of property speculation. It was then that, in the districts most assaulted by speculators (at that time Barceloneta, Ciutat Vella and Poblenou), graffiti reading “the city is not for sale” appeared.

We ask Miquel de Moragas what has changed on the city’s map of symbols from 1888 to now. “What changes is the influence of advertising, which, from 1910 and 1920 onwards, came to occupy an extraordinary space in the urban fabric right up to the present day”, he replies. “The city has turned into one big advertising billboard and the public space is being privatised and hypercommercialised.”

Façades and advertising: the case of the ‘megabanners’

Photo: Italo Rondinella.

During the 15-M protest camp on Plaça de Catalunya, the neutral tarpaulin that covered the Bank of Spain building, when under construction, was replaced by advertising for a sports footwear brand and FC Barcelona.

It was May 2011 and the whole of Barcelona, part of the international media machine andsocial media in particular were all watching closely as to what was happening in Plaça Catalunya: the 15-M protest camp. For months the Bank of Spain building had been under refurbishment and was covered by a tarpaulin depicting its façade, as city regulations require. With all the media attention focused on the square, after a few hours a giant advertising banner appeared for a brand of sports footwear, depicting the FC Barcelona team. It featured on the front page of half the world’s press.

In those days, Barcelonians were still taken aback by these megabanners. In just five years they have been gaining ground on traditional façade illustrations. This new prêt à porter iconography has now been joined by surprise publicity actions (Columbus wearing the FC Barcelona shirt in 2013, the Nike logo on the front of the MACBA building for a few hours); secret publicity actions (the announcement of who would be headlining Primavera Sound 2014 was given one day in November 2013 on Avinguda del Portal de l’Àngel); mobile publicity actions (Vodafone is on all the public hire Bicing bicycles); and flat screen publicity (the metro started to fill up with advertising TV screens in 2011).

These new advertising landmarks adapt to their settings: they visit the monuments that until now took us back to the past and to memory, and they talk to an ephemeral entertainment society, as Gilles Lipovetsky calls it, or to a liquid society, to use Zygmunt Bauman’s concept.

Miquel de Moragas points out that, despite all this, Barcelona has not yet reached the level of commercialisation of public space that is seen in other cities: during Ana Botella’s term as Mayor of Madrid, Line 2 of the metro incorporated a telecoms brand into its name. It was recently announced that this contract would not be renewed when it expires this summer.

For the time being, Camp Nou, one of Barcelona’s symbolic landmarks, has not yet adopted the name of a bank or airline as other sport stadia in Europe have done: since 2006 Arsenal’s ground has been the Emirates Stadium and in 2011 Manchester City’s home became the Etihad Stadium.

Cobi killed Snowflake

© Carmelo Hernando.

El mono blanco, photomontage on the white gorilla Copito de Nieve, a symbol of the city that concealed a colonial past.

Andrés Antebi is an anthropologist, a member of the Research Group on Social Exclusion and Control (GRECS), and we meet him at La Principal, a café-bar on the border between El Raval and El Eixample, a landmark for anyone crossing Plaça de la Universitat. In April 2016, La Principal is teeming with hipsters (beards, Macs, iPhones, looking for sockets) and passing tourists. A French couple takes a selfie with a beer and some patatas bravas. One click and it’s on the Internet. A friend comes to their table: a Frenchman who lives in Barcelona. “This is my bar”, he says.

We meet with Andrés Antebi to talk about iconography and the monumentalisation of the colonial past, and what starts to emerge is the debate on the city’s official image, the policies and motives behind this narrative and how a monument changes when it is thought about from a historiographical perspective that takes into consideration the interplay between urban planning and the production of symbolic landmarks.

Antebi states that the political and cultural interests that explain the city’s imagination have always been the objects of careful consideration, criticism, change and political intervention. The appearance or disappearance of monuments in the public space or changes to street names are examples of this. One of the most symptomatic examples is the whirlwind of names given to Avinguda Diagonal, as it has been called since 22 June 1979, which replaced the name “Generalísimo Franco” that it was imposed on it on 7 March 1939. This latter name had, in turn, replaced the name “14 d’abril” by which it had been known since 16 April 1931. Prior to that, since 13 January 1925, it had been called “Alfonso XIII” and, if we go even further back in time, its original name of “Gran Via Diagonal”, bestowed on it in 1865, would be changed for the first time in 1874 and, at one time or another, part or all of Avinguda Diagonal has also been named “Argüelles” and “Nacionalitat Catalana”.

Another example was the proposed street names for the new city neighbourhood, El Eixample, put forward in 1863 by the journalist and politician Víctor Balaguer, at the request of the Barcelona City Council, in his book Las calles de Barcelona (The Streets of Barcelona). Balaguer argues that the streets should honour “some of the great acts of bravery, righteousness, virtue, self-sacrifice and patriotism that can be presented as examples and models for future generations”. He proposes Pau Claris (proclaimer of the Catalan Republic in 1641), Lepant (after the Battle of Lepanto), Entença (a 13th century expedition captain), Roger de Flor (13th century military adventurer). This is the A to Z of El Eixample, the book based on the marble street plaques we know today.

At La Principal, while Antebi takes us on a journey around the naming and the monumentalisation of the city, the French couple snap another selfie, this time with their friend. Antebi points to the monument on Plaça de Goya, on the other side of the café window. It is dedicated to Francesc Layret i Foix, a local nationalist and republican politician, lawyer and defender of the workers’ movement, who was murdered by a gunman of the Catalan employers’ Sindicato Libre in 1920. Who remembers him? The sculpture, by Frederic Marès, was officially unveiled in 1936, taken down at the end of the Civil War and re-erected on the same site in 1977. Who knows this? Buses, taxis, passers-by and tourists go by, brushing past it. It seems that no one sees it, or at least no one stops to see it.

“Barcelonians don’t remember the person depicted on this monument. A monument is always a failed attempt: it is doomed to oblivion despite the political intentions of those that erected it”, says Antebi.

Photo: Camilla de Maffei.

The sculpture that Frederic Marès dedicated to Francesc Layret, a lawyer and defender of workers (1936).

We talk about Antonio López (a Spanish colonial shipping magnate), about the battle of the iconographic symbols in Barcelona that, according to Antebi, has to do with the city’s past and what it aspires to be. “Some groups are critical of the colonial past and do not want the city to acknowledge this leader; instead, they want to turn the site of his monument into a space of remembrance, while others want to keep it”, he explains.

Antebi is part of a research group on Barcelona’s relationship with Equatorial Guinea. The research has resulted in an exhibition entitled Ikunde. Barcelona, metrópoli colonial (Ikunde. Barcelona, colonial metropolis), which can be seen at Barcelona’s Museum of World Cultures. “We asked ourselves what significance Copito de Nieve (Barcelona Zoo’s albino gorilla “Snowflake”) had towards the end of the dictatorship and into the 1980s. And we wondered about the forgetting of the colonial system, this system that led to the albino gorilla ending up in Barcelona. In the late 1950s, the Barcelona City Council had set up a mining and business system in Guinea.”

Also on the subject of the city’s iconographic narrative, in September 2014 the MACBA organised a collective exhibition called Nonument, inviting twenty-eight artists to think about the proliferation of symbols that have colonised Barcelona’s real and virtual spaces. On the website that explains the project, it says: “Behind monuments lies a certain appropriation of the collective space, an abduction of social memory, as well as the difficulty in embracing pluralities without stereotyping them, and the need to cast out any doubts or uncertainties.” And it asks: Who supports a monument? Who legitimises it? How does it emerge? How does it become rooted in the community and the public sphere?

Architect Álex Giménez was one of the artists invited to take part in Nonument. In the interview he gave us in El Raval (next to the hotel that is lit up in fuchsia tones at night) he also talked about Antonio López and the fact that Barcelona still has a square that bears the name and has a statue of someone who made his wealth through human trafficking. The monument to the first Marques of Comillas can be found at the end of Via Laietana, very close to Roy Lichtenstein’s Barcelona Head, one of the abstract sculptures erected for the Barcelona Olympics.

Despite the fact that in the summer of 2015 the City Council announced that it would rename the square, the sign still reads “Antonio López y López de Lamadrid, Marquess of Comillas (Comillas, 1817 – Barcelona, 1883). Trader, shipping magnate and banker”.

In October 2014, Giménez formed part of a group of activists and artists who stuck a sheet of paper onto the square’s marble name plaque and under Antonio López’s name they wrote “Slave trader”. On the plinth that supports the sculpture, they rolled out a manifesto explaining the context around the figure of the Marquess. In Nonument, he explains, “we created a giant condom that was meant to cover the pole of the Catalan flag outside the Mercat del Born. We arranged it to coincide with World Aids Day”. In the end, they couldn’t cover the flag because of the wind but “it was a real spectacle. A form of protection”.

How do we portray ourselves?

Maria Luisa Aguado, head of Barcelona City Council’s Historic and Artistic Architectural Heritage Department, says that it is impossible to define a single symbolic or iconographic itinerary of Barcelona: there are as many as there are visitors, just like in other European cities.

“Barcelona is a staunch supporter of contemporary art”, she highlights as something that sets the city apart. “These are pieces that have caused controversy but we’ve taken the risk. For example, L’estel ferit, Rebecca Horn’s sculpture on the beach.”

The city has even forgotten the controversy and L’estel ferit has in fact become a landmark of the more “cultured” side of Barcelona, as are Frank Gehry’s fish, Claes Oldenburg’s matchsticks, Botero’s cat, Jaume Plensa’s enormous suitcase, James Turrell’s play of lights, Mario Merz’s neon digits and Lothar Baumgarten’s Rosa dels vents. All these works, and others, form part of the Cultural Olympiad of 1992.

“How do we portray ourselves?” is a question that is taken up by the current debate. In recent months, La Virreina has been hosting an exhibition entitled Barcelona. La metròpoli en l’era de la fotografia, 1860-2004 (Barcelona. The metropolis in the age of photography, 1860-2004), which looks at symbolic landmarks and how photographic depictions of the city have evolved since the time of the first iconographic photographs in the 20th century to the period of urban marketing and new social movements between 1992 and 2004.

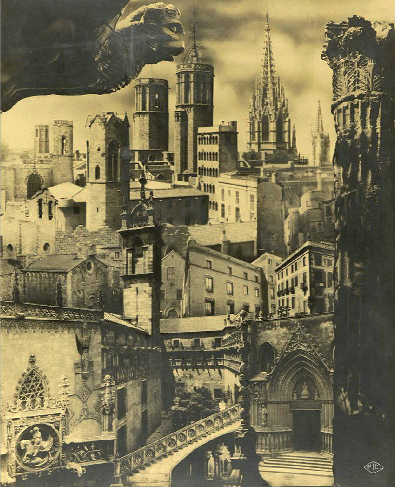

Photo: Pere Català Pic / AFB.

Photomontage of the Barri Gòtic for the Societat d’Atracció de Forasters, 1935.

In 1935 Pere Català created a photomontage with all the official symbolic landmarks of the 1930s for the Sociedad de Atracción de Forasteros (Society to Attract Visitors): it includes the gargoyles of the Barri Gòtic, Hadrian’s Column, the Church of Santa Maria del Pi, the main cathedral, the building of the Catalan Regional Government, and so on. In 2016 both foreign and local eyes are able to recognise that this photomontage represents Barcelona, even after 81 years. Nevertheless, the composition shows how difficult it is to choose an isolated landmark: no single object can explain the fabric and the fusion of the city.

Columbus, always Columbus

In all the interviews there was only one landmark that kept appearing: the monument to Columbus. This naval explorer is there on the postcard racks. He’s a souvenir, a gift bought in the museum shop and a t-shirt. He’s always there on the changing, fuzzy skyline, in the tourist’s selfie, on the roundabout, on TripAdvisor and at the airport, in the institutional advertising and marketing. His monument is visited by 130,000 people every year. He is a look-out point, an advertising medium for the city’s football club and a part of this colonial Barcelona now under discussion.

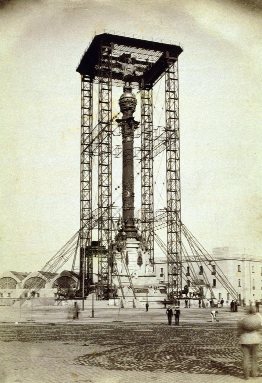

The Columbus look-out column arose on the initiative of a city bigwig in 1852. In 1881 the competition to design it was won by the architect Gaietà Buïgas, and there were more competitions for each figure on the monument, which was inaugurated on 1 July 1888, twelve days after the opening of the Universal Exposition.

Photo: Antoni Esplugas / AFB.

The monument to Christopher Columbus under scaffolding during its construction in 1887. In the bottom left-hand corner of the photograph, Les Drassanes, just about visible.

Will Columbus survive the battle of the iconographic symbols? Will there be a debate about the discoverer like there is about Antonio López?

The exhibition at La Virreina includes a photograph by Antoni Esplugas, dated 1887, of the construction of the monument to Columbus, which we show here on page 101. In it, we see the seafarer surrounded by scaffolding, but the city is hardly visible because the camera lens, the voyeur, is seeking out the new, what was not there before, what will change the urban landscape until something even newer appears and replaces it.

Zuckerberg, by the way, didn’t go near the Columbus monument, nor did he put it on the Internet: it fell outside his 16 km route.