Barcelona is a city with one of the most important photographic heritages in Europe. Public and private archives, antique dealers and collectors, journalists and historians, publishing houses and, in particular, families themselves are all part of the system that makes it possible to preserve and disseminate this valuable documentary heritage.

Many descendants of the creators of family photo albums are aware of their value as historical documents and they keep them; others, however, get rid of them. With a bit of luck, the discarded photographs end up in the hands of collectors who save them from destruction. In the picture, visiting cards with children’s’ portraits, dating back to the late 19th century, from the author’s private collection.

Foto: Eva Guillamet

Barcelona is a city with one of the most important photographic heritages in Europe. It’s not just the numerous public and private archives that preserve images of great documentary value for posterity; many families have also kept photographs, in shoeboxes or biscuit tins or, in the best case scenario, in bound albums, that have obvious sentimental value for their owners but can also give us a whole new vision of the city and of interest to the wider public.

In many cases, old photographs of grandparents and great-great-grandparents stand as unique testimonies to Catalan daily life and society during much of the 20th century. Public and private archives, antique dealers and collectors, journalists and historians, publishing houses and, in particular, families themselves are all part of the system that makes it possible to preserve and disseminate this valuable documentary heritage.

“Someone once said that a book is a box full of things. A box can also be full of stories, of many lives: forgotten, damaged, yellowed boxes… that are now lying hidden in an old chest of drawers. Boxes full of photographs. Some of them may even have been spared this undignified end and have a more prominent place in the drawer, in an album with a simple, faded ribbon. The condition of these ribbons is directly proportional to the love and care that someone put into collecting these images to record his or her own existence. Recovering these boxes is to capture our own presence.” With these poignant words, spoken during the 1998 Primavera Fotogràfica photography festival, the people running the Art and Culture Space at Pere Quart House, a cultural association in Sabadell, paid tribute to domestic photography and its value not only as historial and cultural document but also as a means of strengthening individual and collective identity.

Two years previously, in 1996, the Catalan Regional Government had presented its Llibre blanc del patrimoni fotogràfic a Catalunya (White paper on photographic heritage in Catalonia), which, surprisingly, drew attention again (as had already occurred at the First Catalan Conference on Photography in 1980) to professional, artistic photography but largely ignored the importance of photographs kept in the private collections of amateur photographers who, in many cases, produced hundreds and thousands of pictures that were often of great interest.

Neither does the latest national plan on photography, ratified by the Catalan government in 2014, seem to acknowledge the importance of the hidden photographic heritage that is kept in the homes of the children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren of the people who took the pictures. In the best cases, their descendants value and are aware of the emotional importance that these pictures have, not just for their family identity but also for the general public. The dramatic upheaval caused by the Spanish Civil War, both for institutions and the public, give these photographs from the middle of the 20th century a significance that the people who took them could never have imagined. The snapshots kept in countless shoeboxes and biscuit tins and, in the best case scenario, in pre-war bound albums have today become a unique testament to the Catalonia of yesteryear.

Cultural heritage in a state of emergency

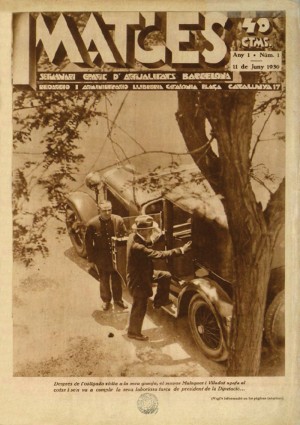

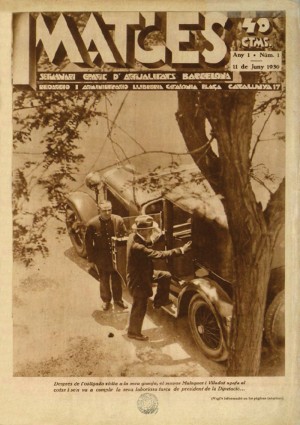

The first edition of the photographic current affairs weekly, Imatges, published on 11 June 1930. The front cover features the politician and lawyer Joan Maluquer i Viladot, as he “takes his car to fulfil his demanding role as President of the Provincial Council, after the obligatory visit to his farm”, according to the caption.

Photo: Arxiu de Revistes Catalanes Antigues

After the end of the dictatorship, the Fundació Joan Miró organised, in 1980, the First Catalan Conference on Photography. During the working sessions, there were debates on the benefits of recovering the country’s photographic heritage, the systems for creating local archives and the need for a museum of Catalan photography which, more than three decades on, has still to be realised. In addition to identifying the main problems regarding the lack of public policy on conservation and dissemination of photographic heritage, delegates also highlighted the exceptional richness of the many archives of non-professional photographers that, often, were in danger of being lost.

And not just those of amateur photographers. Many of the archives of professional photographers were saved from being pulped just in the nick of time. In this regard, the work carried out by the late Miquel Galmes in safeguarding the Roisin, Merletti and Thomas collections, among others, at the historical photographic archives of the Institute of Photographic Studies of Catalonia (IEFC), is truly remarkable. The year 1980 also saw the creation of the National Archive of Catalonia (ANC), although it only opened its headquarters in Sant Cugat del Vallès much later, in 1995. Over the years, its well-stocked Department of Images, Graphics and Audiovisuals has become one of the most important photography collections in the country.

Over the course of the 20th century, there were already several projects and organisations that had helped to conserve the photographic heritage of amateur photographers to great effect. One example is the Excursionist Centre of Catalonia (CEC), whose photographic archive has amassed more than 750,000 pictures over a hundred-year period. It is one of the most important heritage centres in the country, and in order to enhance its collections it has relied largely on donations from its members, many of them keen photographers. It’s a similar situation with the Catalan Photography Association (AFC), founded in 1923, which often shared members with the Excursionist Centre. More than 25,000 plates, most of them stereoscopic, form part of their historic archive. A few years later, in 1929, the National Library of Catalonia (BC) received one of its most valuable private donations: the collection of Dr. Josep Salvany, which comprised 18,000 stereoscopic glass plates that have been studied in depth by the photographer Ricard Marco.

During those years, the Sants chapter of the Excursionist Union of Catalonia (UEC) set up the neighbourhood’s first historical archive. It was 1931 and the people involved were well aware of the importance that all those pictures by amateur photographers, the club’s own members, would have in the future. Over the decades, the Sants Historical Archive (AHS) survived repression and Franco’s dictatorship to create a valuable photographic section that, in the years since the restoration of the democratic City Council, has helped to create what is today the Sants-Montjuïc District Municipal Archive (AMDSM).

Public programmes

Since the mid 1990s, various campaigns have been launched by public institutions with a view to recovering and disseminating home photography collections, which are undoubtedly valuable in building a richer, more plural narrative of 20th century Barcelona’s civic history. Year after year, the Barcelona Municipal Archives (AMB) and, in particular, the Barcelona Photographic Archive (AFB) and the network of District Municipal Archives, receive new collections thanks to private donations. Les Corts archive has, from day one, benefited hugely from a valuable photography collection spanning several decades and donated by the Brengaret i Framis family, who are well-known in the area. In 2015, Horta-Guinardó received the collection of amateur photographer Jaume Caminal, whose pictures are a chronicle of the neighbourhood’s transformation since the late 1930s.

In parallel to the work done by the City Archives (AHCB), education centres and history courses have also played a key role in identifying and protecting private collections, thanks to their in-depth knowledge of the locations in which they work. This is the case with, among others, the Poblenou, Fort Pienc and Roquetes-Nou Barris historical archives; the history workshops held in Gràcia and El Clot-Camp de l’Arpa; and not forgetting the work of the Poble-sec Historical Research Centre (CERHISEC) and organisations such as the Feast Association of Plaça Nova.

The network of community centres and civic participation in every neighbourhood has been a key factor in strengthening local collective memory with visual heritage. By way of example, campaigns to collect family photographs have been launched by municipal civic centres such as that of Barceloneta, Casa Golferichs, Sagrada Família and Casa Elizalde. In 2011, the latter launched an ambitious project entitled “Finestres de la memòria” (Windows of memory), which is still running. Capitalising on the potential of social media, it set out to find photographs of the neighbourhood pre-1980, the aim being the collective creation of a virtual photographic collection.

Over the years, this project has presented several annual exhibitions with themes ranging from the urban and architectural landscape; shops and businesses; domestic interiors; the history of the Sagrat Cor-Diputació School; portraits of local residents inside and outside the home; and public outdoor festivities. In May 2016, it opened an exhibition called “Ens fem una foto? Fotografia domèstica als anys trenta” (Shall we take a picture? Domestic photography in the 1930s). In the words of the organisers – photography historian Núria F. Rius and photographer Jordi Calafell – it was an acknowledgement of the historical value of family or domestic photography in the 1930s, which is when photography reached its apogee. “Taken outside or at home, intimate and personal, these images reveal a different visual story of daily life in L’Eixample that both complements and contradicts the received ideas that have been consolidated about the Second Spanish Republic, thanks to the strength of the graphic press and of cinema”, said Núria F. Rius.

A passer-by stops at a newspaper stand on La Rambla to look at the first copies of the magazine Barcelona gràfica, 9 April 1930.

Foto: Josep Maria Sagarra / AFB

The growing popularity of amateur photography coincided with the irreversible boom of the graphic press in Barcelona. In April and June 1930 respectively, two new picture books conquered the city: Barcelona gràfica (Graphic Barcelona) and Imatges (Images). The academic Teresa Ferré pointed out that, in parallel to this, there was a growing interest among readers in the private lives of public figures, particularly in the world of show business and what was known as the ‘star system’ of the inter-war years. It was another manifestation of the new popular culture that had triumphed in the United States and that, via London and Paris, was now spreading across the whole of Europe. Just as projects like “Finestres de la memòria” look at domestic photography in the Eixample area – and increasingly in the rest of the city, as we can see from the new project on the 1970s Transition years – other initiatives cover the whole of Catalonia. The National Library of Catalonia and the Catalan Regional Government’s Department of Archives and Museums are just two of various organisations highlighting Catalonia’s family memory as a focal point of the “Fem memòria” (Let’s remember) project. Photographs are one of the document types brought along most often by participating families.

Social media and private enterprise

Social media has made it possible to launch dozens of new initiatives to recover domestic photographs or private collections. One example is the blog Barcelofília. Inventari de la Barcelona desapareguda (Barcelophilia. An inventory of the Barcelona that once was) created by the digital activist Miquel Barcelonauta (2010). Another is the Facebook page Barcelona desapareguda (2013) (Vanished Barcelona), set up by Giacomo Alessandro, who died young in 2016 of leukaemia. Yet another is the Instagram account El nostre arxiu fotogràfic (2015) (Our photographic archive) by the young archivist Adrián Cruz Espinosa. All three are laudable initiatives that raise awareness of an unknown photographic heritage. All three have one thing in common: the presence of numerous unpublished photos from family albums.

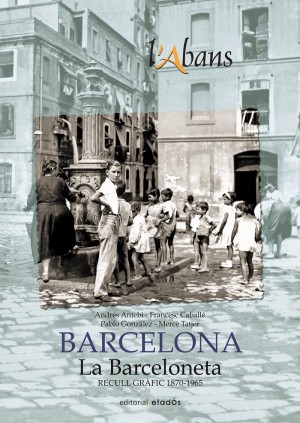

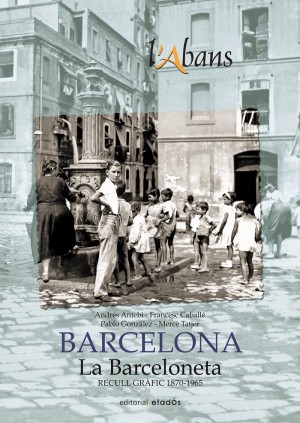

Cover of the book on La Barceloneta from the “L’Abans” collection, published by Efadós in partnership with Barcelona City Council. The collection portrays the history of the towns of Catalonia and the Balearic Islands, in pictures.

Alongside the public actions, private enterprise has also helped in this process to reappraise our heritage. In 1994, the Viena Edicions publishing house started to publish a collection of small books entitled Imatges i Records (Images and Records), which gave prominence to family photographs in its graphic history of towns and districts. The first book focused on the municipality of El Prat del Llobregat, and a few years later, in 2003, the first two Barcelona titles came out, dedicated to the neighbourhoods of Gràcia and Ciutat Vella respectively. Around the same time, another publishing house, Efadós, started publishing an ambitious collection: “ L’Abans” (Before). It achieved unprecedented success. From the very first book in 1996, which focused on the municipality of El Papiol, to the last one on Barcelona’s Ciutat Vella, being released to coincide with Sant Jordi in 2017, more than a hundred volumes have been published, each of them with around a thousand pictures. In total, over the past twenty years or so, “L’Abans” has published more than 100,000 photographs. The volumes on Barcelona have all been produced either by professional historians or, in most cases, by the education centres and history workshops that had already been using domestic photography for years as a key part of their research and teaching projects.

New sources of documentation

The abundance of these potential new sources of documentation, the plurality of visual testaments that they provide and the fact that they are unpublished mean that family photographs are an indispensable resource for researchers studying the 20th century. Certainly, one of the periods that can benefit most is the Spanish Civil War years. Although just a few days after Franco’s troops occupied Barcelona, on 7 February 1939, the press published a release from Franco’s new National Propaganda Service calling for the “collaboration of photographers, experts, reporters and private persons who have taken photographs of official functions, parades, public events, etc., from 18 July 18 1936 to the present day” and asking them to “hand in any negatives and copies of these photographs at their disposal as soon as possible”, the fact is that many people did not obey this order from the new, much-feared regime. Rossend Torras Mir was one of them. To this day, his descendants still preserve his incredible photographic archive of around 25,000 negatives, which they hope will soon be published in full. The collection includes unique photographs of the churches that were set alight in July 1936. “It is time to open shoeboxes and confront the collective memory with photographic evidence. Without doubt, domestic photography gives us a new insight into the Spanish Civil War”, point out photography historian Núria F. Rius and photographer Jordi Calafell.

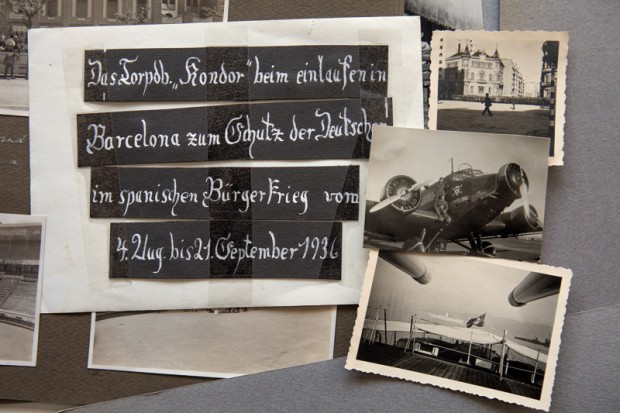

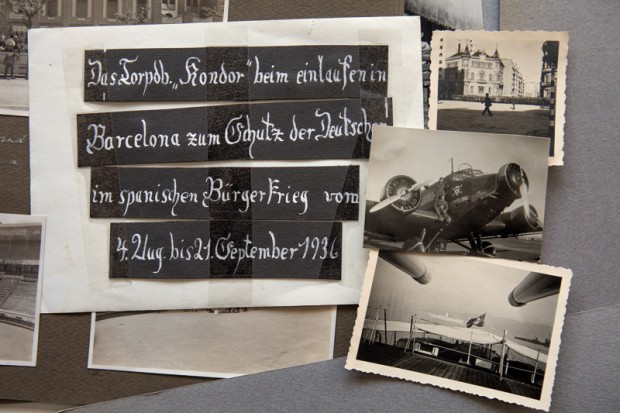

Photographs taken by Nazis during the Spanish Civil War, from the author’s private collection. The text is copied from the back of the photograph of a Nazi ship, the Kondor, which, as the text states, was anchored at the port of Barcelona at the start of the war. Top right, as they occupy Barcelona, Franco’s troops parade at the junction of Avinguda Diagonal and Carrer de Balmes; in the middle a Junker 52 at Burgos aerodrome, with a skull and the name of the target – Barcelona – painted on it; below, a swastika flies at the port.

Foto: Eva Guillamet

It’s not only in Catalonia and Spain that new possibilities are opening up thanks to family photographs. Many grandchildren of the Germans and Italians who, during the Spanish Civil War, fought for Franco’s rebel army, are also donating family albums that capture the military exploits of their Fascist ancestors. Antique dealers, collectors and online auction sites offer these unpublished documents for sale to anyone who is interested. That was the case with, for example, a disquieting photograph in which a group of soldiers from the Nazi’s Condor Legion pose at Burgos aerodrome next to their Junker bomber plane. A spine-chilling skull has been painted on the plane, along with the name of one of the targets of their murderous bombs, dropped at the service of the fascist cause: the city of Barcelona, which, as we know, was never on the frontline of the war. The idea was simply to spread panic among the civilian population of the Republican rear-guard, and indeed they did in Guernica and in the villages of Castelló, but also in Barcelona, Palamós and so many other Catalan towns. In another photograph, the soldiers are pictured next to the rebel planes and the enormous missiles that brought indiscriminate death and destruction wherever they fell.

In 2016 the Museum of the History of Catalonia (MHC) opened a new exhibition on the part played by Italians in the Spanish Civil War. It included a new perspective of many of the soldiers who took part: through the photographs they took on their own cameras, which in many cases, create a stark contrast between their reality and the cold, calculating rhetoric of the official propaganda.

Photographer Jordi Baron, an antiques dealer who has one of Barcelona’s most valuable collections of old photographs; in his studio holding a daguerreotype.

Foto: Eva Guillamet

For the photographer Jordi Baron (a Barcelona antique dealer with one of the city’s most valuable collections of old photographs), the domestic photographs provide “the human view of the experience. Photojournalists are professionals, so they are detached from the personal or family experience and they are taking the photos for someone else, ultimately, for the public. The wonderful thing about domestic photographs, or what are today called ‘vernacular photographs’, is the purpose for which they were taken: they have no particular intention, they are only for private and family use, they are nothing more than a private document, unless the photographer has the added bonus of artistic expressiveness or he or she wants to share them with other people”.

The hidden heritage of family photographs may be priceless, but it is also very vulnerable and at risk of being wasted or, in the worst case scenario, being destroyed if it is not located in time. We have heard how some collections have been saved from obscurity, and news of them has reached the media, but how many others have disappeared without a trace?

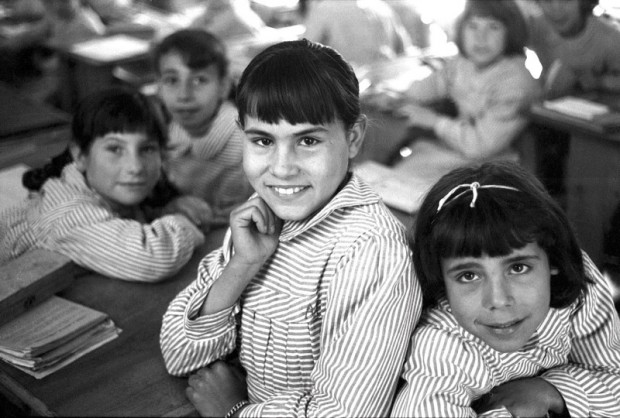

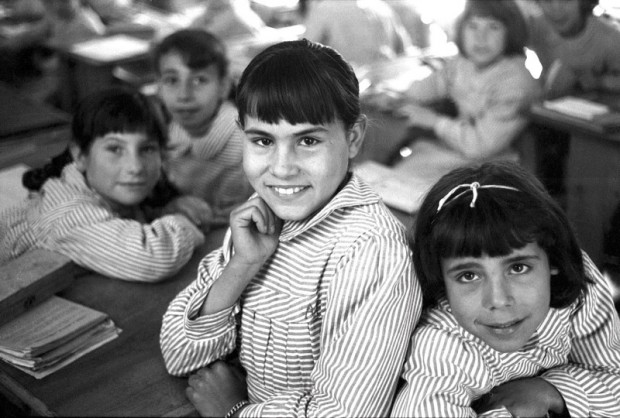

Rosalía Serrano, born 1950, discovered herself as a little girl in this photograph (on the right, with a ribbon in her hair) that was bought in 2001 at Els Encants flea market by a North-American tourist, Tom Sponheim. The picture came in some envelopes containing negatives that Sponheim has taken the time to document on a Facebook page called Las fotos perdidas de Barcelona, which led to the photographer being identified. Rosalía found out about the existence of the photo when watching a report on TV.

Photo: Milagros Caturla / Las fotos perdidas de Barcelona

It was at the Encants de les Glòries flea market that, in 2001, a North American tourist, Tom Sponheim, bought some envelopes with negatives of what appeared to be pictures of Barcelona. When he developed them on his return to Seattle, he became aware that these dozens of photographs had been taken by someone who was very gifted, but whose identity was unknown. Using social media, in particular his Facebook page Las fotos perdidas de Barcelona (The lost photos of Barcelona), Sponheim has been able to document them with great accuracy, thanks to the help of internet users. Some of the people pictured have even been identified. One of the girls appearing in the photographs is Rosalía Serrano Calvo, born in 1950. In late January 2017, she was watching television when she saw a feature on the amazing story of the photos whose author Sponheim was trying to find. When the photographs of some schoolgirls came up on the screen, Rosalía exclaimed that one of the girls looked just like her granddaughter Anabel. But it wasn’t her granddaughter – it was actually her… And this was proven by other family photographs of the time. “I couldn’t believe it. That photo was taken when I was eight years old, at my school, Els Tres Pins, on Montjuïc. We lived right next door”, she remembers.

Unforeseeable Encants

Teacher of Audiovisual Arts and collector, Artur Canyigueral, a tireless hunter of old photographs at Els Encants flea market in Glòries. A Barcelonian by adoption who is passionate about old photographs as a communal heritage that evokes the emotions of a society broken by the Spanish Civil War and the dictatorship.

Foto: Eva Guillamet

Tom Sponheim’s experience is part and parcel of the daily business of Barcelona’s antiques dealers and collectors who, every Monday, Wednesday and Friday, early in the morning, go to Els Encants for the closed auction of lots to be sold over subsequent days. One of them is Artur Canyigueral. Even after going there for decades, the expectation of finding a valuable item is as exciting as it was on his very first day. “Everything is so unpredictable at Els Encants, you never know what you might find. That’s what makes it so magical”, says Canyigueral, who has been frequenting Barcelona’s flea market par excellence since 1973. “It must be over ten years ago now that I bought a lot containing the family photos of a lady in Manresa, comprising about 500 photographs, both developed and in negatives. I could see the potential that lay in the photography of the past: that whole collection showed fixed shots of the lives of three generations of family, like in a cinematic narrative. I was fascinated by it and I reoriented my work towards photography”, explains this affable retired Audiovisual Arts teacher. At Els Encants, Canyigueral the collector has become a tireless searcher of these images, which, since 1839, have illustrated the transformation of contemporary society. “If you look very carefully, you can find images that ring all these changes. You can see the official history in them, but also the heterodox history. They are described and captured in little jewels of trapped time: moments of light trapped by an innocent – or not so innocent – hand, telling us what our ancestors were like and what they did.”

Sometimes, entire lots come into Els Encants, the photographic testament of an entire life. When someone dies without an heir, or if there is no interest in their belongings, including family photo albums, on the part of the third or fourth generation, whose members are often emotionally disconnected from their history, this heritage often ends up on the stalls of Els Encants or in the rubbish bin. But not always. There are also many descendants who are fully aware of how valuable their parents’ and grandparents’ passion for photography is today, not just for the family but for society as a whole.

The daughters of pharmacist Joan Miquel-Quintilla share, on the Barcelona Foto Antic website, a selection of photos taken by their father between 1933 and 1983. There is still much to study in the albums of Dr. Miquel-Quintilla as they include more than ten thousand pictures that depict how society in Barcelona and other locations in Catalonia and Spain evolved over those fifty years.

Foto: Eva Guillamet

This is true of the daughters of pharmacist Joan Miquel Quintilla, who, altruistically and self-funded, created a website called www.barcelonafotoantic.com, where they started publishing a selection of the more than 10,000 photographs their father had taken over half a century, between 1933 and 1983, both in black and white and in colour. Hundreds of albums, yet to be studied in depth, have given us amazing pictures like the incredible view in colour of the slums of Somorrostro closest to the Poblenou seafront, taken in 1962. More recently, the volume on Ciutat Vella in the L’Abans series published for the very first time some of the most emblematic pictures taken by the tailor and photography enthusiast Ramon Beleta, kept by the Figa-Beleta family. It has also brought to light some of the treasures kept in the album of the Solsona-Climent family: photos taken by the Republican schoolteachers Jeroni Solsona Pallerols and Maria Climent Roses.

In these early years of the 21st century, when photography is more popular than ever thanks to the digital revolution and social media, old family photos are back in the limelight and many of us have been sorting through our grandparents’ and parents’ old papers to save their photographs from falling into oblivion. Stories such as the amazing discovery in 2007, by the researcher John Maloof, of Vivian Maier’s negatives, have encouraged us to turn our gaze back to our family albums. More than ever, our domestic photographic heritage is, indisputably, strengthening our collective identity.