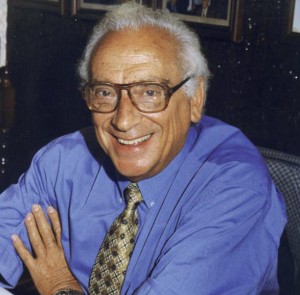

As mayor of Barcelona (1957–1973), Porcioles embodied Franco’s prototypic Catalan collaborator. He played a key role in an operation conceived to clean up the image of the regime; he was criticised for the construction of the sprawling urban Barcelona, but he was also praised for achievements such as the Picasso Museum and the return of the Compilation of the Catalan Civil Code.

© Pérez de Rozas / AFB

Porcioles accompanies Franco in his car on a visit by the dictator to the city of Barcelona on 30 April 1960.

With the passage of time, Josep Maria de Porcioles i Colomer (Amer 1904 – Vilassar de Dalt 1993) has become one of the most paradoxical and difficult-to-interpret figures of the Catalan political scenario, particularly due to the enormous contradiction of his role.

He was on the one hand actively involved in Franco’s dictatorship, being responsible for controversial actions such as the construction of outlying neighbourhoods crammed with immigrants from southern Spain, often veritable suburban corners, such as Ciutat Diagonal, la Pau, el Turó de la Peira, Sant Roc de Badalona, la Mina de Sant Adrià, Bellvitge de l’Hospitalet and many others; and also, among other things, for the partial destruction of Barcelona’s modernist architecture, promoting populist-style tenements, with the famous small attic flats built on top of existing ones, particularly in the Eixample neighbourhood.

Meanwhile, though, Porcioles also felt personally obliged to carry out many other works that, in view of what Franco’s regime signified in Catalonia, must be seen in a positive light. For the first time since Franco’s victory in 1939, Porcioles lent his support to displays of Catalan folklore and popular culture, such as sardana dancing (forbidden by Franco) and the “festa dels tres tombs” (a celebration in which people bring their animals to receive a blessing). He also did a lot to promote the creation of the Picasso Museum and the Miró Foundation. Whichever way you look at it, it was a surprising course of action, stemming from the compensatory side of the jurist’s personality, a man of his time: a sui generis ambiguity, also very “Porciolian”, straddling the positive and the negative, which culminated in 1960 with the historic approval by the Spanish Parliament, following negotiations involving the mayor, of the so-called special Compilation of Civil Law, a landmark largely unknown to most people but one of capital symbolic and juridical importance for the country.

This Compilation adhered to and recovered the former solidity of the historic Civil Code of Catalonia, a collective work that enjoyed the consensus of the Parliament of Catalonia, according full legitimacy to an independent Catalan Law. To put it another way, the recovery of the Compilation, virtually unique and ground-breaking in Europe, restored legitimacy to the series of modern civil regulations that had been suppressed with the Bourbonic invasion of 1714. In a nutshell, at its most basic level, it symbolised the return of people’s civil freedoms.

The Compilation was the culmination of a protracted historical process, the fruit of the cultural Renaissance and political Catalan nationalism, and however contradictory it may seem, it was born of the highly moderate Catalan nationalism of a man who was close to the dictatorship, as if his origins and sense of morality outweighed his political leanings.

Porcioles also addressed the ambitious Barcelona 2000 plan and a universal expo for the city in 1982, which never came to fruition, but which brought up the idea of the Olympic Games. In short, as the housing estates spread chaotically and vertically, it was as if the mayor who had sponsored, built and spawned the speculation and private business in that Barcelona of the sixties, ravaged by the post-war period, had fallen prey to a bout of schizophrenia, which would also affect numerous key characters in the regime, such as Joan Antoni Samaranch. Franco’s former national delegate of Physical Education and Sports became obsessed with bringing the Olympic Games to Barcelona in 1992 in an ambitious personal campaign designed to clean up his image with his countrymen and also for the sake of posterity, in all probability because he had raised his hand firmly during the dictatorship. Porcioles is a similar case.

When the dictator hand-picked him as mayor of Barcelona in 1957 he knew what he was doing. The loyal Director General of Records and Notarial Affairs of the Ministry of Justice, also an experienced notary public in Barcelona and member of Parliament, was the ideal man for the job. Porcioles would be mayor for four consecutive mandates; sixteen years on the trot. But the choice of Porcioles was prompted by the urgent change of tack that Franco was obliged to undertake at the end of the fifties, a significant example of which is the return of the Catalan Compilation.

According to the notary public of Barcelona, Lluís Jou, this volte face by the dictator, “apart from the mayor of Barcelona’s power of persuasion, is part of the economic change strategy undertaken two years previously, and which – according to Jou – became known as Operation Catalonia, an attempt by Franco’s regime to garner greater sympathy in our country, to allay the suspicion generated by the new economic policy and gain credibility abroad for its policy of opening up the country, which could only be successful if it was done through Catalonia”. Jou also asserts that “it is a strategy that Porcioles also promoted in the belief that closer collaboration would squeeze greater concessions” out of the dictator. This may be so, but paradoxically the recovered Compilation spurred the regime on, and Porcioles thus played a key role in Franco’s regime opening up towards new political and economic models; it enabled his great Barcelona, with all its characteristic and disconnected ambiguities, to become indispensable for the Spanish state to be able to join the international economic institutions.

© La Vanguardia news archive

Cover of the La Vanguardia newspaper from 21 July 1960 announcing the approval by Franco’s parliament of the special civil law codification, and an image of the mayor addressing the court agents.

Porcioles, as a Catalan integrated in Franco’s regime, embodied the ultimate great paradox. During his spell as president of the county council of Lleida (1940–43), for example, he recovered the cathedral, which had been turned into an army barracks by Philip V, and set up the Institut d’Estudis Ilerdencs there, a pivotal cultural centre in the area of Lleida. As mayor of Barcelona, he is accorded the merit of promoting a special law for the city, the Barcelona Charter, which gave him presidential-like powers, dispensing with the regime’s structure; the idea and implementation of the system for using water from the river Ter for the water supply were also his; he also secured the return of the mountain and castle of Montjuïc to the city and fostered all kinds of trade fairs and congresses as well as the initial investments in the underground in the wake of the Civil War.

Porcioles was a church-goer, a man of profound beliefs, wise; he had an aristocratic, stately bearing, and the fact that he had difficulty uttering certain words (he had a stammer) made him more endearing, restrained, distant. But what mattered most was that he was a notary public. A man who could be trusted, who had followed in his father’s and grandfather’s professional footsteps. He passed the official examination to become a notary public in 1932. He had also been local leader of the Catalanist party Lliga. When the Civil War broke out he eventually fled to France after spending a few months in the Model prison. On his return, he embraced the natural destiny of many liberal right-wingers: he adapted to Franco’s regime and even adopted its most censurable and negative traits. With the slogan of “the best path is from revolution to concord”, as mayor of Barcelona he was harshly criticised for promoting excessive inner-city traffic through projects such as the Ronda del Mig, Avinguda Meridiana, the Vallvidrera tunnels and the network of paying car parks.

In the case of the Vallvidrera tunnels, he was blamed for leaving the project unfinished because the tunnels cause traffic jams going into Barcelona along Via Augusta. This infrastructure was supposed to link up with another major road that would cross the city as far as Carrer Numància and even reach Montjuïc, which would have greatly improved rush-hour traffic, but which evidently never came to fruition. Others have accused him of doing away with the trams and of over-municipalising public transport with the introduction of the city bus, because this measure failed to alleviate car pressure in the city. But beyond all this criticism, some of it really harsh, the fact that Porcioles made Barcelona a modern city in line with the world’s great cities and, with all the related pros and cons, also one of the world’s most visited and admired is beyond any dispute.