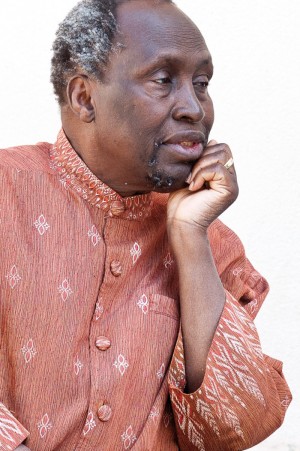

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o rouses passions in western universities with his denouncement of colonial acculturation. He came to Barcelona for the first time 20 years ago to sign the Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights, which he regrets has not yet been internationally adopted. His presence at the CCCB in May last year drew a lot of attention.

Photo: Albert Armengol

For the Kenyan novelist and essayist Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, language is the custodian of identity and a tool to be used against colonial domination. On the publication of several of his books in Catalan and Spanish translations, the Catalan PEN Club invited him to the CCCB to speak on writing and emancipation.

The Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o is often better known here for his essays in defence of minority languages than for his novels. Although he started writing in the sixties, until a few years ago it was very difficult to find Spanish or Catalan translations of his works. But in recent months, several of his works have been published in both languages: Decolonising the Mind; Moving the Centre; Dreams in a Time of War; A Grain of Wheat; Devil on the Cross; Weep Not, Child… And to coincide with these publications, Ngũgĩ visited Barcelona on the invitation of the Catalan PEN Club, to give a lecture at Barcelona’s Centre for Contemporary Culture (CCCB) on “Africa, Writing and Emancipation”.

Caitaani mutharaba-Ini (Devil on the Cross), Ngũgĩ’s first novel in Gĩkũyũ, was written in 1968 on a roll of toilet paper, while the writer was in prison and denied writing paper. Half a century later, the author jokes that it was “lucky” the prison toilet paper was not at all soft and one could write on it quite easily. This anecdote clearly positions Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o among the socially or politically active African writers who have been persecuted for defending people’s rights but who, despite everything, have never renounced their beliefs.

After leaving prison, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o continued to voice his beliefs through writing. When he published one of his next novels, Matigari, the authorities ordered that he be imprisoned, along with Watigari, the main character in the book. Obviously they were not able to imprison Watigari, but Ngũgĩ was forced into exile. When he briefly returned to his country in 2004, he was viciously assaulted and decided to leave again.

His novels are a denunciation of social injustices. A Grain of Wheat is a choral novel that tells of the British repression of the Gĩkũyũ people in the 1950s, during the time of the Mau-Mau – an episode in history that he also recounts to great effect in Weep Not, Child and in the first volume of his memoirs Dreams in a Time of War. But his disenchantment with the new political regimes that had been set up in an independent Africa was already obvious in Petals of Blood, one of his earliest novels. Since then, he was to continue to denounce the injustices suffered by his country. It is not insignificant that Ngũgĩ is Gĩkũyũ, one of the ethnic groups that fought most against colonialism in Africa and that paid for it with brutal repression.

Africa is fertile ground for socially committed authors who have put up a challenge to the lack of freedom and denounced abuses of power. Some of them have paid for it with prison sentences (like Wole Soyinka in Nigeria and Ahmadou Kourouma in Ivory Coast), with exile (Mongo Beti from Cameroon, Donato Ndongo from Equatorial Guinea and Emmanuel Dongala from the Republic of Congo) or even with their lives (such as Ken Saro-Wiwa in Nigeria). But we must also remember that there are many authors in Africa who have played an active role in political regimes that have little respect for freedom: take Léopold Sédar Senghor, former President of Senegal; Boubou Hama, President of the National Assembly of Niger in the 60s; Henri Lopes, former Prime Minister of Congo-Brazzaville; and Jean Pliya, who held ministerial positions in Benin.

The power of local languages

In 1968, following a stint at the University of Leeds in the UK, Ngũgĩ returned to Kenya and decided to write for the theatre, as a way of reaching his less literate compatriots more directly. And he opted to write in Gĩkũyũ. Up to that point, the author had never had any problems with his revolutionary novels written in English, but now he was put in prison and only freed after pressure from the Pen Club. While in prison, he became aware of the powerful impact of using local languages: if he had been imprisoned, it was because his plays, in Gĩkũyũ, had reached a wider audience than his works in English. It was then that he took the decision to only write fiction in African languages.

Unlike the vast majority of African writers who opt to use the colonial languages that have official status in their countries, Ngũgĩ put up a passionate defence of the use of native languages, arguing that to reach the general public, one has to use their language and that a language is the expression of an identity. Through his reflections on the subject, he came to realise that his struggle was not just that of the Gĩkũyũ people, but of many speakers of marginalised languages: Lapps, Maoris, Native Americans… According to Ngũgĩ, around the world there are people who believe that their languages are inherently superior to others and they impose “linguistic feudalism”.

Ngũgĩ is, then, the most Catalan of African writers. Identity is a recurring theme in his work, as it is for many African writers, especially those of the Négritude school. But Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o went further than they did and saw language as the custodian of identity and as a tool to be used against colonial domination. For him, real decolonisation has to involve the negation of colonial negation (he argues that colonialism was based on negating the identity of the colonised). And he states that he wants to “open up to the world” from what he is, his “base”. As the Catalan song La Balanguera goes: “the trunk gets longer the deeper the roots”.

Back to Barcelona

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o had already been to Barcelona twenty years ago, although his visit created much less expectation then. He had been invited by the PEN Club to sign the Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights (or the Barcelona Declaration), a manifesto calling for the protection of marginalised languages. Ngũgĩ laments the fact that this document, which sounds to him like “music for the stars”, has yet to be implemented across the world.

Ngũgĩ recognises that the situation of African languages is only getting worse, that there are parents who take pride in the fact that their children do not understand the language of their grandparents, that many writers have turned their back on their mother tongues… But he says that revitalising marginalised languages is the task “of our shared humanity”. Because all languages “are sources of beauty and infinite possibilities”.

A star author and a leading theorist

While twenty years ago Ngũgĩ went almost unnoticed, today, in 2017, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s talk at the CCCB attracted a large audience. His courageous defence of minority languages was undoubtedly a major factor in the way this Kenyan was received in Catalonia. But there was another reason behind this level of expectation: in recent years Ngũgĩ has become a leading theorist in the field of cultural studies. This Kenyan author arouses veritable passion, especially in western universities, for his denunciation of colonial acculturation. But he is given a rather cooler reception by African writers who write in French, English, Portuguese and Spanish. Some of them remind him that they were never taught to read or write their own language, as Ngũgĩ was, or that there is practically no one left who can read their languages.

But maybe the real key to understanding the warm welcome given to Ngũgĩ actually lies in the changes that Barcelona has gone through. This is a city that reflects more and more on its past and its relationship with others. Today, it is a capital city that explores the colonial past through exhibitions such as Ikunde, through a wide range of symposia and numerous publications. And it is also starting to question itself about its past involvement in the slave trade by means of themed trails, and by debating street names and the presence of certain monuments… A Barcelona that questions itself and that is starting to take a good look at itself, through the eyes of others.