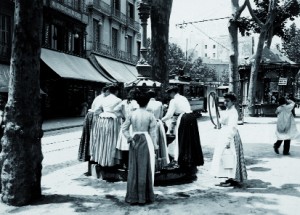

One of the two Wallace fountains that remain on the streets of Barcelona. Located in front of the Comedia cinema, on the corner of Gran Via and Passeig de Gràcia, it has been perfectly restored and is in full working order.

Photo: Albert Armengol

Major changes to Barcelona’s water supply in the second half of the 19th century, at a time of incredible urban expansion, brought a huge rise in the number of drinking fountains. Against this backdrop, fountains in the style of Paris’s emblematic Wallace fountains became part of the city’s heritage.

In percentage terms, Barcelona is the city with the most drinking fountains in Europe, with a density of a little over one fountain per 1,000 inhabitants and an approximate total of 1,650 units. We are not counting fountains for ornamental purposes, those that are not used to quench the thirst of passers-by. The high number of fountains is mainly due to the difficulties that arose in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in establishing a single efficient and economical water supply to homes.

Historically, the construction of each new infrastructure associated with water supply has always been followed with the inauguration of a new group of fountains. Thus, for example, during the 14th century, one of the first public fountain networks was established when water collected from the springs and mines of the Collserola hills was brought into the city. The fountains located in Plaça de Sant Miquel and Plaça del Blat, now gone, were the most central and important. The city’s oldest three fountains still in use are also from this period: the Santa Anna fountain (1356), where Carrer de Cucurulla meets Avinguda del Portal de l’Àngel; the Sant Just fountain (1367), located in the square of the same name; and the Santa Maria fountain (1403), just in front of the basilica of Santa Maria del Mar.

The Santa Eulàlia fountain at Plaça del Pedró, in a picture from around the end of the 1850s or start of the 1860s.

Photo: Pérez de Rozas / AFB

A significant second series of fountains was incorporated into the city with the opening of the Montcada aqueduct in 1826. Six were built in total, all unique. The first, in Plaça del Pedró, is dedicated to the city’s patron, Saint Eulalia; it is a monument that was turned into a fountain and inaugurated as such on Saint Eulalia’s day (12 February) in 1826, to celebrate the arrival of the first water through the aqueduct. The second is dedicated to Hercules, the city’s mythological founder; it is situated on Carrer Nou de la Rambla and was inaugurated in September 1826. The fountains on Carrer de la Cadena, in Plaça de Sant Pere, Barceloneta and L’Andana de la Marina all followed. Only the first two still survive.

The water revolution

A period of great expectations with regard to the growth of the city began during the second half of the 19th century and as a consequence expectations of the growth of water consumption grew too, which led to transformations of the water supply. Following the approval of the Pla de l’Eixample (Expansion Plan), the citadel built by Philip V and a large part of the walls were demolished, and the population increased significantly.

By 1826, the Montcada aqueduct had already been inaugurated, an essential infrastructure that indicated a certain stability in the supply of water and made it possible to undertake the approved urban reforms with a degree of confidence. There was also a series of advances in hydraulic technology that, in addition to the new business organisation systems, were to turn water into another product of the capitalist marketplace. This then drove the emergence of the business environment of the Industrial Revolution.

Businessmen and entrepreneurs working in the water sector enjoyed a euphoric business climate based on the anticipated urban growth resulting from the development of the Eixample district. Modern buildings and new forms of hygiene and home comforts led to expectations of a large increase in domestic water consumption; water would also be necessary for irrigating and cleaning the new streets, parks and gardens and other urban spaces, where more fountains would also need to be built, all in addition to the creation of modern municipal services and facilities with significant water requirements, such as markets, slaughterhouses, fire-fighters, etc.

Moreover, we mustn’t forget that there were still some years to go until the arrival of electricity as the main energy source and, at the time, the set-up of any new industrial plant or the enlargement and improvement of existing factories were based on steam technology. Industry was still displacing the surrounding populations, and the manufacturing premises in Ciutat Vella and the Sant Pere neighbourhood, large water consumers, were still very active. Ultimately, the water business was facing the future with excellent prospects, so the city was targeted with money from new businesses and companies aspiring to become suppliers for the city.

From the 1870s onwards, because of its obvious lack of financial capacity and its subordination to the national authorities and urban landlords, the city council was unable to alter the water collection and distribution infrastructures at the rate the city needed, and this left enough room for a large number of companies – some with enough capacity to supply barely a few blocks of the Eixample district – to begin ambitious projects. The phenomenon was extended to the towns neighbouring Barcelona, which had not yet been annexed to the capital at that time.

Then, a new water law passed in 1879 authorized and provided business confidence to a practice that was already fairly widespread: obtaining profits from the private operation of hydrological concessions to supply the population.

Up to then, Barcelona’s fountains had always been supplied by publicly owned water. The emergence of new operators brought an end to this; but despite everything, the fountains continued to provide a free service to the public thanks to the agreements established between the city council and the various concessionaires.

From the Companyia d’Aigües to SGAB

Two prominent events in the modernisation of the water supply occurred in 1867: the start of the construction of the Torre de les Aigües water tower by the Associació de Propietaris de l’Eixample (Eixample Property Owners’ Association) and the establishment of the Companyia d’Aigües de Barcelona (Barcelona Water Company – CAB).

Detail of the ‘Torre de les Aigües’ in the Eixample district. The plaque showed its ownership.

Photo: Vicente Zambrano

Just a few years after it was founded, the CAB was already able to supply water to Gràcia, the central area of L’Eixample and Ciutat Vella. “It operated a groundwater concession in Argentona and Dosrius, bringing the water to Barcelona via a closed aqueduct to a tank located in El Guinardó […], offering for the first time in Spain metered service contracts”1, an innovation that enabled payment according to consumption.

The ‘Torre de les Aigües’ in the Eixample district, which architect Josep Oriol Mestres and engineer Antoni Darder began building in 1867. It is located on the block formed between the streets of Roger de Llúria, Bruc, Consell de Cent, and Diputació. Today it forms part of a public garden.

Photo: Vicente Zambrano

This great business activity in the 1860s and 1870s brought what some authors have defined as the water revolution.2 Every company wanted to contribute improvements to the supply and to colonise as much territory as possible with their supply network. Just a couple decades later, the euphoria began to wane. The demand was not as high as expected and the competition between companies became fierce, while the investments needed for water collection infrastructures and distribution networks were beyond the reach of the majority of new suppliers. This led to the merging of a large number of small suppliers and the takeover or failure of many others. The concentration of businesses was swift and comprehensive, to the point that in 1896, for example, the service supplying L’Eixample was now in the hands of the Barcelona General Water Company (SGAB), the new French-owned company that came out of the liquidation of CAB.

Duplication of the supply network

From then on, a dual supply network began to be established. On one hand, SGAB’s network (there were other companies, but they were very localised), which brought water via the aqueduct from Dosrius to El Guinardó,, and from here distributed it to half the city; and on the other hand, the public network that continued to supply part of the city, basically Ciutat Vella and La Barceloneta, from the Collserola mines and via the Baix de Montcada aqueduct.

This municipal network was intended, in principle, to cover public services, such as the fountains on the newly developed land, irrigation, public toilets, cleaning, markets and the sewage system based on Pere Garcia Faria’s project, which required a continuous flow of water to work correctly, provided that these services were located in the area of influence for distribution from the Baix de Montcada aqueduct; outside these limits, the city council was obliged to buy water from private companies. As noted by Manel Martín in Aigua i societat a Barcelona entre les dues exposicions (1888-1929) (Water and society in Barcelona between the two expositions (1888-1929)), the differences in the municipal service were nevertheless indicative of the level of modernization of the two collection, piping and distribution networks. The municipal fountains did not have taps, they had a continuous stream, “the result of a supply system based on piping that used rolling water”, by gravity, “and with an almost total lack of distribution control elements: with no suitable tanks and no mechanisms to regulate pressure”.

The public network was to have these shortcomings for many years, despite the fact that in some periods liberal city governments tried to improve it. For many years, the dual system produced a rivalry between the municipal and commercial operators, which was to a large extent fictitious, as there was considerable dependence on the private supply.

The Wallace fountains appeared on the street of Barcelona in this context of dual network and a certain degree of competition between SGAB and the city council.

Street art: fountains and street lamps

The last three decades of the 19th century were also a time of great activity when it came to installing fountains. We have already mentioned that, firstly, the new Eixample district had to be equipped with enough public fountains, and, secondly, certain emblematic spaces had to be fitted with unique street furniture, as part of the big drive to improve and embellish the city. Together with the lighting, the fountains were some of these urban pieces that were raised to the category of art and that we still have today.

Examples of the unique street lamps include those on Passeig de Gràcia, Avinguda de Gaudí – moved from there to the junction of Passeig de Gràcia and Avinguda Diagonal – as well as those in Plaça Reial or on Passeig de Lluís Companys. Also from this period are the cast iron fountains with a column crowned by an agave plant and the fountains by municipal architect Pere Falqués (1850-1916) for Plaça de Sant Pere and Rambla de Canaletes. The latter, which over the years would become the emblematic fountain of Barcelona, brings together two basic elements of the municipal public services: water distribution and lighting, represented by the four taps and the lamps that crown the column.

Iron had already spread across Europe as a structural element of construction, and now it also took on an important role in the normalisation and modernisation of the urban landscape. Cast iron was the material chosen for the new street furniture, as an exponent of the contemporary technology and a symbol of modernity. It is therefore no wonder that it was also the material chosen for fountains in the majority of European cities, including Barcelona.

Base of the fountain located at the end of La Rambla, together with the name of the company that supplied the water – la Sociedad General de Aguas de Barcelona –, the city’s emblem, and the inscription “agua tomada directamente del contador” [water taken directly from the meter]. You can see the shell-shaped basin together with its spout, which was added to the original fountain at a later date.

Photo: Albert Armengol

Between romanticism and marketing

The Wallace fountain also falls within this context of organising services and equipping the urban environment with furniture. It is a model manufactured by the prestigious French Val d’Osne foundry, in the Alt Marne department in northeastern France.

The most commonly-held version of its origins says that in 1872, Sir Richard Wallace (1818-1890), an English millionaire philanthropist, commissioned the French sculptor Charles-Auguste Lebourg (1829-1906) to design different fountains to alleviate the water supply and distribution problems from which Paris was suffering.

Richard Wallace was a highly regarded figure in the world of art and art collecting. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, he became a distinguished Paris philanthropist: he financed a hospital, he distributed provisions and cared for soldiers wounded during the siege by the Prussians. Among other things, it is said that he also created an ambulance corps, which he paid from his own pocket.

It appears that, drained of resources, the French capital found it very difficult to guarantee the distribution of water and that in places that it did reach, a price had to be paid that was unaffordable for much of the population. As related in a chronicle published in 1921 by the magazine Hojas Selectas, “walking through Paris one day, and being thirsty, Wallace thought about the unfortunates who could not, like him, satisfy such an urgent need in any nearby establishment, and thus were born the drinking fountains that bear his name.”3 Wallace donated around 50 fountains to Paris and the Northern Irish city of Lisburn. Three different models were made: the large one – the most common and successful – as well as a small one and a wall-mounted one.

Below, the upper part of the fountain on La Rambla de Santa Mònica, replicated on the right in a satirical cartoon from an 1892 copy of the weekly L’Esquella de la Torratxa.

Photo: Albert Armengol / ARCA Arxive

Moved by the effects of the post-war period, he also designed the biggest and most elegant model to serve as a symbol of the brotherhood of the peoples of Europe. He proposed “to create a chain of friendship between the peoples, the links of which would be represented by these fountains”,4 and with this aim he commissioned hundreds of pieces to donate to the major cities of Europe. The design, which met with great success, led the manufacturer to sell and distribute them in many other cities and countries around the world for years to come.

According to this same version of the story, circulated by various authors, it was Wallace himself who gave Barcelona 12 units on the occasion of the Universal Exposition of 1888.5 The information we present here, practically as an exclusive, is the result of the research we have conducted in archives and publications, and conversely it suggests that the fountains arrived in Barcelona on the initiative of the French investment group that in 1882 founded the Société Générale des Eaux de Barcelone in Paris, known here as the Societat General d’Aigües de Barcelona (SGAB).

This new supplier could thus have been the promoter and introducer of this model of fountain as a publicity stunt and with a purely commercial interest, completely irrespective of the original intentions of Richard Wallace. There are details that corroborate this or at least cast doubts over the more widespread legendary and romantic version.

To date, no document has been found and there is no news of any formal act of reception of the fountains by the city council, nor is there any entry in the municipal record books from 1884 to 1890 that mentions the fountains. Neither do we have any record of any publication or newspaper that includes the news of receiving or installing these 12 fountains that were supposedly gifted to the city. This is strange, as something like this would have been an important public event.

But it is also strange that Wallace, with his good wishes of brotherhood between the people and nations of Europe, did not make this donation to Madrid, the country’s capital, or at least share the donation between the two most important cities in Spain.

Personalised examples

It is also worth adding that unlike the fountains in other cities, the originals preserved in Barcelona are personalised with the city’s coat of arms and an inscription alluding to the supply company. As explained above, a dual supply network was established during the final years of the 19th century, owned by the council and by private operators. The private network, despite it being much more recent, was already almost exclusively held by SGAB. How insensitive it would have been for Wallace to give a gift to a city and put on it the name of a company which at that time was competing with the city council to supply water!

Under the coat of arms and inscription, which are repeated on two sides of the fountain, there is another text that, although it may seem banal today, was not at the time: “Water taken directly from the meter”. Over the course of the century, Barcelona had suffered various episodes of infectious diseases, some of which were attributed to contaminated water.6 The information given on these fountains, situated in strategic places, that the water did not come from tanks, but from a meter – which provided more health guarantees – may be interpreted as a marketing manoeuvre by SGAB.

From the point of view of the municipal technicians and politicians in charge and even of public opinion, it is also worth noting that, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Wallace model was the great novelty in urban fountains, the fashionable fountain from Paris, where the company was headquartered. The French capital was the most important city in Europe at that time and Barcelona copycatted it; for many years everything that came from Paris was guaranteed success in our city.

In terms of the date they were introduced, we have not found anything specific, but there is a comic from the satirical magazine L’Esquella de la Torratxa from 30 September 1892 about the recent installation of one of the fountains on the Rambla. As well as the clear intention of criticising the private supply of water, the tone of apparent surprise in the comic suggests that this example could be the first that was seen on the city’s streets. In any case, it is unquestionable that at least one fountain, this one, did not arrive for the Universal Exposition of 1888.