One of the earliest Catalan female researchers, Teresa Bracons, a member of Doctor Ferrer i Cajigal’s team. Doctor Ferrer set up the Museu Anatòmic Patològic (Museum of Anatomical Pathology) of the Faculty of Medicine, in a picture from 1930. Bracons can be seen seated beside Ferrer i Cajigal, in the centre.

Photo: Fundació Museu d’Història de la Medicina de Catalunya

Officially, science was a man’s affair in Barcelona until very recently. This can be seen, for example, in the gallery of names of illustrious academics in the Paranimf of the University of Barcelona, which only includes one woman: 17th-century philosopher Juliana Morell. However, if we look under the surface, we find that women have in fact been involved in the scientific and technical life of the city in many different ways: often secretly, from spaces less hostile than the academic world, or rebelliously, questioning the patriarchal components of the scientific paradigms.

If in the 1920s and ‘30s women gained an unprecedented role in the world of science in Barcelona, the arrival of Francoism resulted in a setback that wasn’t reversed until the ‘70s. Nevertheless, women found new ways of taking part in science. The end of Francoism and an ideological shift among women resulted in a fundamental change: female registrations at university schools of science multiplied, as did the names of notable female scientists. However, the impact of this change was much more significant, because it also modified society’s view of science and health.

The impact of women in science in modern Barcelona (from the end of the 19th century to today) goes far beyond a handful of famous female researchers. We also need to focus on the patients at the clinics in the Eixample, the prostitutes in the Barri Xino and their role in public health policies, on amateur astronomers, female laboratory workers, “Museum girls” at the Museum of Natural Sciences during Francoism, the groups interested in legalizing abortion in the post-Franco period…

“For centuries, women couldn’t enter the academic world: in Spain, they needed parental authorization until 1910. But furthermore, history has ignored their contributions: it wasn’t until the ‘90s that the history of science began to wonder about feminine knowledge”, observes Mònica Balltondre, a researcher at the Centre for the History of Science at the Autonomous University of Barcelona (CEHIC-UAB). “Women’s contributions are more than notable from the 19th century onwards, but they’re made invisible. Often, women had another way of cultivating science, because of the limitations they faced”, agrees Pedro Ruiz Castell, a researcher at the Institute “López Piñero” for the History of Medicine and Science at the University of Valencia.

“In Catalonia, we have a historiographical deficit on this issue. It’s something we need to look into”, affirms Alfons Zarzoso, curator of the Museum of the History of Medicine of Catalonia. “Dr Miquel Fargas became the father of Catalan gynaecology thanks to articles like the one based on a thousand ovariotomies. We know very little about the women that endured these operations. Who were they? Why were they operated on? Were these operations necessary? How was their time at the clinic paid for?”, asks Zarzoso.

Another example are the health campaigns against venereal diseases carried out from the end of the 19th century to the first four decades of the 20th. “In all these campaigns, women, and especially prostitutes, are identified as the source of the problem. This group becomes faceless, anonymized”, explains the curator of the Museum of the History of Medicine.

Around the 1920s, the presence of women in the world of science began to be a common occurrence. There are plenty of photographs of laboratories featuring women, though unidentified and in the background. The picture shows a group of people at a lecture by the well-known Doctor Josep Agell, founder of the School of Directors of Chemical Industries, in this body’s laboratory in 1916.

Photo: Frederic Ballell / AFB

We need to look for another way

“It’s not that there’s always been an attempt to make them invisible. The problem is that women don’t appear in the sources as much as men. But there are ways of tracking them down: behind this supposed non-existence there’s activity and value” affirms Emma Sallent del Colombo, a researcher at the University of Barcelona and the president of the Catalan Society of History of Science and Technique. “Historians aren’t blind; we just have to investigate differently”, indicates Oliver Hochadel, a researcher at the Milà i Fontanals Institution (CSIC) in Barcelona.

“We need to focus on the supposedly subordinate roles: wives that help their researcher husbands, collectors, museum workers, secondary-school teachers, activists… Or organizations like athenaeums, astronomical associations, hiking associations…”, states the researcher. Hochadel notes that at the beginning of the 20th century, research wasn’t as institutionalized as it is today: many individuals who would now be considered amateurs made fundamental contributions to science.

“From the groups meeting in aristocratic salons to athenaeums and the banquets of scientific societies, we know that women would often attend, either as organizers or participants. This oral culture played an important role, but it’s been hidden”, explains Agustí Nieto, an ICREA researcher at the Autonomous University of Barcelona.

“You can also do science outside of the laboratory”, insists historian Mònica Balltondre. One of the first areas where this became evident at the beginning of the 20th century was in pedagogy, a field that is more tolerant to female participation. “We know of a ton of women who went to congresses, but they didn’t do their research in the laboratory; they did it in the classroom”, adds Balltondre. One example was María de la Rigada, an Andalusian pedagogue who taught at the Superior Normal School of Teachers of Barcelona, among other institutions. De la Rigada was a pioneer when it came to finding objective measurements of what was then considered the intelligence of children. “These tests are a way of overcoming the old, subjective classification of smart kids and stupid kids”, explains the researcher from the Centre for the History of Science.

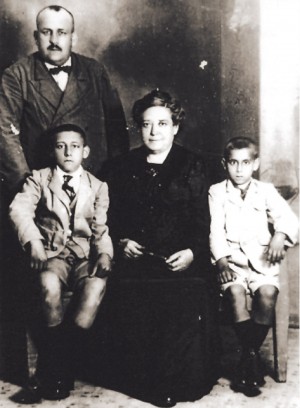

Women demonstrating in La Ciutadella in favour of secular education, on 10 July 1910. The demonstration was organised by the Barcelona group of feminist activists and freethinkers linked to the writer Ángeles López de Ayala, the anarchist worker Teresa Claramunt – who we see beside these lines in Seville with the photographer Antonio Ojeda and their children.

Photo: Antonia Fontanillas Archive

The amateur world was another way women could access science. “[In 1890], the British Astronomical Association was born in the United Kingdom as an alternative to the Royal Astronomical Society: the subscription was expensive, their publications were too technical, and… women couldn’t participate”, explains Pedro Ruiz Castell.

In 1910 and 1911, the Astronomical Society of Barcelona and the Astronomical Society of Spain and America were born in Barcelona, both founded by astronomer Josep Comas i Solà. “Many women attended these societies’ conferences. Comas i Solà had female collaborators. For example, his wife served as his assistant during the eclipses of 1900 and 1905, and the group he founded at the Fabra Observatory in 1920 included the mathematician Assumpció Ferrer”, adds the researcher from the University of Valencia.

“Women’s ways of participating in science also depend on their situation. If they’re from a bourgeois household, they can read, keep up-to-date and participate in debates. In other groups, women don’t want a scientific career: what they want is for science to help them gain greater autonomy, to become the masters of their own bodies”, Hochadel observes. “We can’t put the category of social class below the category of gender”, states Nieto.

The explosion of spiritism

Within this joint framework of social class and gender, we can understand the explosion of spiritism in Barcelona in the first few decades of the 20th century. Today, spiritism is a sort of superstition, but in those days it was seen as just the opposite: it was a plausible scientific theory that offered a rational, modern alternative to religion. According to Balltondre, “spiritism was seen as a scientific field that sought to determine whether the soul was immortal. For years, it tried to communicate with spirits using scientific trials and controls.” The movement was quite successful for some time, but was later pushed aside.

Research by this historian has shown that spiritism was a very important phenomenon in Barcelona, strongly rooted in neighbourhoods of skilled labourers and liberal professionals like El Raval, Gràcia or Sant Andreu. “These groups had disconnected from the Catholic religion, and they saw spiritism as a modern alternative, in solidarity with anticlerical movements and attempts to secularize society”, she states.

Women played a central role in spiritism. First of all, mediums were traditionally women. “Mediums started to have a certain degree of power in spiritist societies as well as a place in public spaces: they would give talks, write in publications. Through the spirits, they would speak and write about their vision of morality and the progress of humankind”, explains Mònica Balltondre. One of the most charismatic mediums, Amalia Domingo, even founded a magazine, La Luz del Porvenir (The Light of the Future).

Second, spiritism sought to wrest power over schools from the church. Some of its tenets were equal educational opportunities for both sexes and mixed-gender education.

Third, spiritism promoted a female workers’ movement. “Working women were looked poorly upon in the mid-19th century: they were practically considered prostitutes, someone their husbands couldn’t support”, indicates the UAB historian. Anarchist attempts to make groups of working women had failed. Once again, this was finally achieved by Amalia Domingo. Together with anarchist textile worker Teresa Claramunt and libertarian and masonic writer Ángeles López de Ayala, in 1890 she founded the Autonomous Society of Women, which would later be called the Feminine Progressive Society. In the words of Balltondre, “the movement of free-thinking women that existed in Barcelona at the end of the 19th century was ground-breaking in Spain: it’s hard to say whether they were the first feminists, but they were most likely the first ones in all of Spain to make feminist demands.”

Alternative collectives

Science was a popular topic of debate in other antihegemonic groups in the early 20th century, from the naturists to the herbalists. One of the most active was the anarchist movement. In its publications, for example, there was deep debate on the question of contraception. During the first seven years of the 1930s, the anarchist magazine Estudios had a lively “Questions and Answers” section on health-related topics. This section promoted an intense debate between two doctors and other readers regarding the Ogino birth control method. Finally, one of the doctors asked the readers for help to find statistics on the method. In general, anarcho-syndicalist militants were sceptical of experts, since they considered them a part of the machine they were fighting against.

In the ‘20s and ‘30s, the female presence in the world of science began to become hard to hide. “We have many photographs of laboratory teams where we start to see women in the second or third row. Who were they? Where did they study?” asks the curator of the Museum of the History of Medicine of Catalonia, Alfons Zarzoso. From 1924-1939 there was a Museum of Pathological Anatomy at the University of Barcelona. “There were women working there that were more than just technicians; they were already taking part in research”, notes the president of the Catalan Society of History of Science and Technique, Emma Sallent.

Gradual incorporation into higher education

This increasingly-visible role of women is due to their gradual incorporation into higher education starting in 1910. While Dr Abreu (one of the first female doctors in Barcelona, who got her licence at the beginning of the century) had to be accompanied to the university to avoid problems, free access of women to higher education was one of the ideas defended first by the Commonwealth of Catalonia and then the Republic (“even though, without a doubt, there was also a great propaganda effort on this issue”, observes Emma Sallent). During the first decades of the 20th century, “there was more of an increase in the women registering for scientific pursuits –especially pharmacy– than others like law”, notes Alfons Zarzoso.

Members of the Institut de Fisiologia (Institute of Physiology) of the Barcelona Faculty of Medicine, around 1925. Among them, in the second row, Antonia Papiol, Montserrat Farran, Maria Bosch and Josefa Barba. Barba, a graduate in Pharmacy and Law, was an emblematic character in research in her day.

Photo: Fundació Museu d’Història de la Medicina de Catalunya

One significant figure from this period was the researcher from Barcelona Josefa Barba. A bachelor of pharmacy and law, she specialized at the Residencia de Señoritas in Madrid— the female version of the Residencia de Estudiantes attended by Dalí, Lorca, Buñuel… Thanks to scholarships from the Junta de Ampliación de Estudios (part of the Institución Libre de Enseñanza) and the Maria Patxot Foundation, in the ‘30s she went on research trips to the United Kingdom and to Johns Hopkins University in the United States. Barba broke with the conventions of her time: for example, she travelled alone and didn’t want to have children.

Doctor Maria Lluïsa Quadras-Bordes in her gynaecological surgery at the Institut Electrològic i Radiològic (Electrological and Radiological Institute) in Barcelona, in 1921.

Photo: Brangulí / Arxiu Nacional de Catalunya

However, not all women with higher educations were progressives. Sisters Maria Lluïsa and Victòria Quadras-Bordes, for example, showed business initiative and reached powerful positions in medical institutions, but they were ideologically conservative, states Zarzoso. In any case, he notes, “in the ‘30s Barcelona was unmistakeably advanced and modern”, more so than many other European cities.

Francoism against women

The researcher notes that “Francoism brought about a sort of collapse for women, who didn’t recover until the ‘70s.” During the Civil War, Josefa Barba left for the United States, where she had a long career that put her work in publications like Science. In 1939, the Museum of Pathological Anatomy of the University of Barcelona was shut down entirely. “Some of the men involved continued to work in medicine. The women all became housewives”, Emma Sallent states, ironically. “After the war, women were limited to paediatrics or obstetrics, branches related to women as mothers and wives, or to the world of clinical analysis, where they worked in isolation, without interacting with patients and were socially invisible”, Zarzoso explains.

Students and teaching staff at the Institut de Segon Ensenyament per a la Dona (Secondary Education Institute for Women) on a visit to the Fabra Observatory on 5 March 1911, listening to the explanations by the director of the centre, the astronomer Josep Comas i Solà.

Photo: Frederic Ballell / AFB

Inauguration of the premises of Aster, Associació Astronòmica de Barcelona (Barcelona Astronomical Association), on 3 June 1949. In the image a significant female presence can be seen.

Photo: Aster

Nevertheless, during the dictatorship several opportunities appeared in the world of science that had been barred in more politicized areas. “Some organizations serve as refuges, little bubbles of freedom”, states Hochadel. One example is Aster, the Barcelona Astronomical Association, founded in 1948 as an alternative to the Astronomical Association of Spain and America, which had become very professionalized. “The Barcelona Astronomical Association (Aster) is related to an alternative sort of sociability; it represents a place where there’s room for women”, observes Ruiz Castell. The presence of women on the board is minimal, but there are a significant number of female members, especially in certain commissions like the one on bolides. In addition, there are multiple donations from women for the construction of the dome of the Association’s observatory. Part of the success of this organization has to do with the famous celebrations they would organize after their conferences. Some of the complaints about the supposed promiscuity at these events reveals the presence of women, according to the researcher from the University of Valencia.

Another unexpected opportunity came from the elimination of researchers and technicians by the Francoists, what would later be known as the atroz desmoche –atrocious decapitation– using an expression by Pedro Laín Entralgo. “It’s horrible to think about, but that did open up a little space for women”, says Hochadel.

The “museum girls”

The Natural Sciences Museum in Barcelona had female employees since the 1920s. In 1916 no women were mentioned in the museum’s annual report, and in 1917 there were about a dozen. They often began as secretaries, but many took botany courses and were later promoted. Over time, this group came to include about forty members, who were eventually nicknamed the “museum girls”.

“When some of the men were purged, the women stayed. They were the ones who knew how the museum worked, how to manage the collections. There wasn’t much room, but some women took advantage of this little space to have really impressive careers”, Hochadel explains. He especially notes Roser Nos, a Valencian scientist who moved to Barcelona at a young age. As opposed to many of the “girls”, Nos didn’t start out doing administrative tasks at the museum; she arrived as an intern as a result of her studies in natural sciences. She worked at the Museum of Zoology from 1947-1961, and afterwards at the Zoo until 1978. She then became museum director, a position she held until 1989.

The recovery of the ‘70s

The end of Francoism and a shift in ideology among Spanish women resulted in a significant change in the relationship between women and science. In the 1970s, female registrations at the science schools of universities grew exponentially. From then on, the number of notable female scientists continued to rise. However, the impact of this change goes even further: it changes the way science is seen, especially with regards to health.

“Under Franco, sex was basically seen as having to do with reproduction, not pleasure. In the ‘70s, women begin to claim their right to their own bodies, to sexuality and sexual education” explains Sara Fajula, an archivist at the Doctors’ Association of Barcelona. Several years prior, in the previous decade, medical student Assumpció Villatoro had run into gynaecology professors who were within the Francoist tradition, but who had a more progressive attitude. The professor she specialized under, Victor Conill Serra, was a practicing catholic, but he had come to the realization that family planning was a necessity. On the other hand, another professor, Jesús González Merlo, was initially opposed to such ideas.

Starting in the ‘60s, Santiago Dexeus began to offer a secret and private family planning service from his clinic. In the ‘70s, a movement of doctors in favour of family planning appeared. It was made up mostly of men (Dexeus himself, Ramon Casanellas, Eugeni Castells, Josep Lluís Iglesias Cortit, Xavier Iglesias Guiu…), but also included Assumpció Villatoro. Many of its ideas were manifested in “La Gaia Ciencia” book collection created by writer Rosa Regàs, which included a volume by Villatoro on abortion (“What Is Abortion?” from 1977) before the practice was legalized in 1985.

Demonstration in defence of the right to divorce and to abortion, organised by the Coordinadora Feminista del Baix Llobregat (Baix Llobregat Feminist Coordinating Committee) in the early days of the Democratic Transition.

Photo: El Prat Municipal Archive

In 1976 a group of feminists including nurses created the DAIA collective (Women for Self-knowledge and Anticonception). “They thought that feminism was a strong movement, but that it wasn’t doing enough”, explains Fajula. The group counselled women on contraceptive methods in a Barcelona apartment, and saw itself overwhelmed with questions on abortion. The members of DAIA, who were in favour of sexual education and the right to abortion as a last option, offered women advice on safe abortion options, either clandestinely or abroad. The group was active until 1984.

The team of the Prat de Llobregat Family Planning Clinic, the second of its kind in the whole of Spain. It was founded in 1977 by the left-wing activists Carmina Balaguer and Maruja Pelegrín, on the right in the picture.

Photo: El Prat Municipal Archive

The first family planning centres

In 1976, the first family planning centre was opened in Madrid, and in 1977 the first in Catalonia was opened in el Prat del Llobregat. These first centres were initiatives of women rooted in their neighbourhoods, feminist militants or members of the PSUC (Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia), such as Carmina Balaguer or Maruja Pelegrín. “The women who worked at these centres had either studied, or had educated themselves by reading books like ‘Our Bodies, Ourselves’”, translated into Spanish in 1982. But female doctors also got involved, including Assumpció Villatoro herself. They were in charge of medical supervision, and they applied a sort of pre-emptive medicine”, Fajula explains. Many of these centres began to produce data and statistics on how women experienced sexuality, and what contraceptive methods they used. The centres slowly lost their “women for women” philosophy when they became part of the public health service, the researcher notes.

At a time like the present where, in theory, there are no explicit barriers to women wanting to access science, the story of all the obstacles they once had to overcome seems like something from another world. Nevertheless, historians believe that this process holds plenty of useful lessons for us today: no step forwards is permanent, there’s always a risk of sliding backwards. “The fight for the right to family planning is over, but the right to abortion is in a delicate situation”, Fajula reminds us. Balltondre has something to add: “there are still plenty of fields of research and technology where women are practically absent. How many apps are there that address women’s needs? How many women are there in Silicon Valley?”, she wonders.

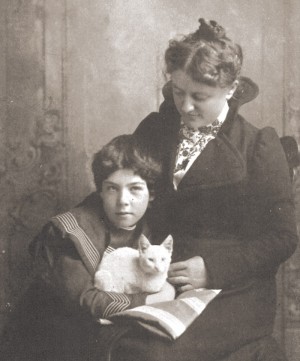

The child psychologist Milicent Shinn (1858-1940) was the first woman to receive a doctorate from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1898. In the photograph she can be seen with Ruth, her niece, the subject of her observations on the psychology of babies.

Photo: Public domain

Research in the crib

The apparent total absence of women in the world of science until a few decades ago is, in part, a result of the objective barriers they found. However, according to historians, it also has to do with a process of making their contributions invisible. In addition, it comes from an excessively restricted idea of science, which is limited to the academic, institutional and official world. Science is much broader, and it includes other spaces (not just the laboratory, but also the workshop, the store, the factory, etc.) and other participants (not just academic researchers, but also technicians, patients, activists, communicators, etc.). If we look at science from a historical perceptive, we can see that these spaces and these actors have always played a fundamental role in expanding scientific knowledge.

It is precisely in the least institutional places and the least academic roles where women have met less resistance to their participation in science. One extraordinary example of this is Milicent Shinn. This Californian housewife turned her home into a laboratory to scientifically analyse the psychology of newborns. Furthermore, she created a network of about fifty observing mothers, and together they put together the largest body of direct observations on the development of babies.

After graduating from the University of California, Berkeley in 1878, Shinn began caring for her parents and siblings in the town of Niles, near San Francisco. In 1890, she started to take notes on her newborn niece. Just a few years earlier Charles Darwin had encouraged scientists to investigate the development of children, and more specifically to observe babies as “natural history objects” and to “bring the argument of childhood into the scientific realm.”

Information accessible to men

Soon, Shinn realized that her detailed diary was an exceptional body of information, accessible to most male researchers who never set foot in a child’s room. By 1891 she had already contacted ten other Californian mothers to carry out coordinated observations of their babies. The network would grow in the following years under the protection of the Association of Collegiate Alumnae (ACA), an organization of female alumni from the most prestigious universities in the US.

In 1893 Shinn presented her first results at the annual meeting of the National Educational Association in Chicago, and she published the first two volumes of her observations on Ruth (she would eventually publish a total of four). Her conclusions refuted the dominant idea that babies first developed their senses and then reason. Shinn established that a series of complex capacities guided the psychological development of babies.

While some scientists valued her work, others questioned its legitimacy. Psychologist James Mark Baldwin argued that a mother couldn’t be a scientific observer, and others stated that women were blinded by their adoration for infants. Shinn answered that women wouldn’t be able to keep a child alive without making objective observations about their behaviour.

The researcher, who obtained her doctorate using these studies, put forward her results in the 1907 essay The Development of the Senses in the First Three Years of Childhood. In 1910 she retired from directing the ACA, a position she had earned in the meanwhile, to care for her mother, nephews and nieces. Nevertheless, she kept up correspondence with the mothers in her network throughout her life.