Ignàsia, daughter of the artisan Pere Claver, and wife to the shoemaker Gaspar Robira, mastered the art of lace-making and engaged in the manufacture of this fabric, which she supplemented with a clothes-making business and money-lending. The industrialist eventually set up a production network that comprised the output of women working in 13 different towns of the area around Barcelona, from Maresme to Baix Llobregat.

It is a known fact that, at least as of the Middle Ages, in Barcelona there were women – single, married and widows – who set up and ran their own businesses, thus contributing to their own and their families’ welfare. This longstanding tradition of women entrepreneurs from Barcelona is little-known, but that does not mean that it did not exist.

This continual presence of women in the business world has certain noteworthy characteristics. Between the 14th and 19th centuries, businesses owned by women were concentrated – as perhaps they are now – in two specific sectors. On the one hand, there was the sale of groceries and different types of food, as well as textiles, ready-to-wear clothes and accessories. On the other hand, there was the manufacture of garments and accessories (gloves, hats, corsets, etc.), and certain fabrics. This concentration of independent female economic activity may be attributed to ideological and economic reasons –reducing competition–, particularly more so as of the advent and dissemination of guilds – as of the 14th century in Barcelona –, which reserved most trades, the best ones, for men.

Nevertheless, a few production activities were never regulated by guilds, thus allowing women to run their own businesses. One of these activities was the manufacture of bobbin lace – called blonde lace when it was made from silk yarn – a luxury product that yielded high profits. It is common knowledge that the sector always employed female labour – for a pittance wage – although it is not so well-known that there were also some very resolute businesswomen. One such woman was Ignàsia Claver i Castells, from Barcelona (Barcelona, circa 1760–Reus, 1811).

This daughter of the artisan Pere Claver, “sifter and screener”, of Barcelona, and of Eulàlia Castells, married the shoemaker Gaspar Robira, also of Barcelona, in the early 1780s. As was the custom, she then took her husband’s surname, and was known as Ignàsia Robira i Claver. This was the formal signature she used. The fact that she was highly skilled in the complex art of lace-making – I know not how – led her to produce this kind of fabric. It should be mentioned that she knew how to write, which went a long way in helping her to do the bookkeeping and, particularly, to take care of the business’s correspondence.

Things were not going so well with the couple, so Ignàsia filed for separation before the church authorities. Apparently, the root of the problem lay in the fact that the family breadwinner was the wife rather than her shoemaking husband. Nevertheless, in 1799 the couple had second thoughts and signed a notarised agreement to resume their relationship, making it clear what the conditions of the economic activity that would support the couple and their four children were to be.

The signatures of Ignàsia and her husband on a notarial document of Antoni Comellas, held at the Protocol Archive.

In the document, the husband acknowledged that the lace business and the company capital belonged to the wife, “who had acquired it through hard work and effort, without jeopardising the economic administration of her home and family”. The husband therefore recognised Ignàsia’s manufacturing and business acumen, her economic independence and the fact that she had generated assets without neglecting her domestic duties. The same document stated that as of that moment the husband would invest capital in his wife’s business, effectively making him her partner. He would thus collect his part of the profits, and the receipts, letters and other papers would add the words “and Company” to the name of Ignàsia’s firm. Another clause in the agreement provided that, “out of generosity”, she would give half of her profits to the husband so that he could attend to “his obligation to feed and dress his wife and children, as any husband and father should”. This was provided that he fulfilled this responsibility; otherwise “he would forego his entitlement to receive half of the profits”. Moreover, Ignàsia delegated to her husband the task of collecting the revenue from the lace business, albeit reserving the power to intervene when she felt it necessary.

The business that Ignàsia had built amassed a capital of some 7,500 Barcelona pounds – besides more than 2,500 pounds in bad debts – which indicates that it was a crafts family and not one from the wealthy, high-class business echelons.

She purchased on credit and is known to have owed more than 3,500 pounds, a considerable sum in view of the business’s capital value. This demonstrates that she enjoyed considerable creditworthiness among her suppliers.

To make up for her loss of clout in the lace-making business, Ignàsia decided to start up a parallel business. She plumped for the sale of fabrics and ready-to-wear clothing. Some of the dresses bore elaborate embroidery work and her clients were not only the people who patronised her shops, as she also had clients in Valencia, Madrid and “America”.

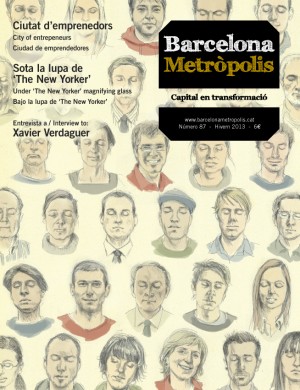

© Luisa Ricciarini / Prisma

German bobbin lace-makers in a painting by the baroque artist Giacomo Francesco Cipper (Todeschini).

We know that by 1803 she had 107 blonde lace mantillas on sale and different lace garments in black and white silk. It should be mentioned that the lace business was not a simple one, as it was based on a network of lace-makers in different locations controlled by an intermediary. The complexity of Ignàsia Claver’s business is notable, since it comprised the output of women working in 13 different towns of the area around Barcelona, from Maresme to Baix Llobregat.

The lace business profits allowed her to amass a certain amount of wealth, which she used to engage in money-lending. In one case she lent more than 500 pounds to the same person.

Ignàsia’s economic standing became very solid, as is borne out by the fact that when her daughter Francesca married the tailor Josep Gustà, in 1803, she gave her a 500-pound cash dowry plus a two-drawer trousseau valued at a further thousand pounds. This all adds up to much more than what Barcelona’s artisans normally spent on their daughters’ weddings. As she was not yet of age, the girl had to ask her father’s permission to be married, but her mother provided the dowry.

When the Peninsular War broke out, Ignàsia decided to move to Reus, where she died in April 1811. Her last will and testament said that she had been living in the town for some months. If she was not already ill when she arrived there then she must have taken ill there, since she did not even have the strength to sign her will.

Her son, Josep Robira i Claver, inherited his mother’s bobbin-lace business, although he never became an important businessman in the sector. He preferred to increase his fortune by purchasing property in Barcelona. This double occupation secured him well enough economically, so much so that his son, Joaquim Robira i Torrabadella, could study medicine and became a doctor and surgeon in 1847. Thus, there is no doubt that the family’s social ascent was based on grandmother Ignàsia’s three-pronged economic activity: bobbin lace-making, money-lending and clothes-making.