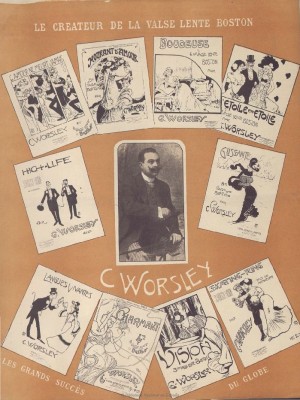

Pere Astort found success in several countries with compositions he wrote himself, inspired by popular music from the other side of the Atlantic. The so-called Boston waltzes made him famous under his pseudonym Clifton Worsley.

Brangulí / Arxiu Nacional de Catalunya

A dance at la Torrassa picnic grounds on Montjuïc

in 1916 or 1917.

Not much is known about the pianist and composer Pere Astort i Ribas, better known – or maybe less unknown – by the alias Clifton Worsley. Despite being one of the most famous musicians in the city of Barcelona at the turn of the 20th century, it is next to impossible to find any mention of him in any history of Catalan music. Great efforts will uncover just a few encyclopaedic references to him, in spite of his importance: a distinguished Barcelonian who found success in the United States with compositions he wrote himself, inspired by the popular music from the other side of the Atlantic. A jazz pioneer from Catalonia? A musical visionary who was able to predict the fashionable trends in Barcelona’s most sophisticated dance halls during the first third of the 20th century? Or just a composer of popular pieces who, without at all realising, wrote waltzes comparable to the music of the first jazz schools? Perhaps.

There is one thing about Pere Astort that we know for certain: he died in Barcelona on 13 March 1925. However, there is some disagreement as to his beginnings. According to some sources – Ramon Civit, for example – he was born in the Catalan capital on the day of La Mercè, its annual festival, on 24 September 1873. According to others – Lluís Brugués in the 2009 essay La música a la ciutat de Girona (1888-1985) [Music in the city of Girona (1888/1985)] – he was born in the city of the river Onyar. Whether he came into this world through the head and heart of Catalonia or the city of a thousand sieges, the majority of his biographers agree in saying that Pere Astort was trained as a musician in the choir school at La Mercè church in Barcelona and, later, he studied piano.

Before adopting the alias Clifton Worsley, Astort had started to become known as a shop assistant at Can Guàrdia, the popular sheet music shop and publisher, which later took the name Casa Beethoven. Ramon Civit, a musicologist and teacher at the Taller de Músics music school – and one of the top Worsley experts – explains that the young Astort met Mercè Gresa (sister-in-law of Rafael Guàrdia i Granell, founder of the sheet music business) at the shop on La Rambla de Sant Josep. The young pianist married Gresa in 1895, and, over time, became one of the most well-regarded employees in the eyes of the select clientele that went to the shop. Lluís Permanyer, a Barcelona historian, recreated the ambience of Casa Beethoven at the end of the 19th century in a 1987 article for La Vanguardia. Citing Anna Maria Guàrdia and an article by the musicologist Francisco Hostench from Liceo magazine, Permanyer talked about the visits to Can Guàrdia made by Isaac Albéniz, Felip Pedrell, the maestro Millet and, especially, Jacint Verdaguer: “make them fly”, Permanyer says the poet declared when he read his verses to some of the greats of Catalan music. At one end of the shop there was (and still is) an upright piano, where the shop assistant Astort sat down to play for a bit.

Legend has it that one day Charles Danton, an American musician, stopped by Can Guàrdia while Astort was playing the piano. Danton was gobsmacked by the style of one of the compositions the pianist was playing. When he found out that the waltz had been written by the man himself, he told him that the work sounded like one of the typical waltzes that were in fashion in Boston, where he was from. He then recommended that Astort change his name to something more American-sounding, suggesting that he call himself Clifton Worsley. In 1899, Astort, or Worsley as he was now known, published his first “Boston waltz” with his brother-in-law’s publishing house, which he named after the American city as a tribute to the man who discovered him. Ramon Civit explains that in that same year, the Banda de Barcelona played the waltz in Parc de la Ciutadella during a typical summertime evening event.

Worsley was presented as “the creator of the Boston waltz”. And what exactly was the “Boston waltz”? Civit talks about a similar genre in the court of Louis XV of France, which made it over to the United States in 1835 thanks to the dancer Lorenzo Papatino. But Astort/Clifton Worsley went even further, according to Ramon Civit: “Despite the fact that this type of waltz – slightly slower than the Viennese waltz – already existed, the young Barcelona composer unquestionably contributed to modernising it, both in terms of its form as well as its harmony”, he points out.

Worsley ended up writing around 200 compositions, some of which were published by Unión Musical Española and by Vidal Llimona y Boceta, in some cases with covers illustrated by the well-known artist Llorenç Brunet, and with traditional names such as: La vaquerita (The Little Cowgirl), La vendedora de moras (The Blackberry Seller), El fracaso del abate (The Abbé’s Failure), Mi serrano (My Mountain-Dweller) and Intrigas cortesanas (Court Intrigues); or in other languages: French (Tes yeux des flames, Encore je t’aime), Italian (Il rosaio, Tu sei lontana) and pre-reform Catalan (Tres cansons catalanas). American soprano and researcher Suzanne Rhodes Draayer lists some of Astort’s most important compositions in her 2009 book Art Song Composers of Spain, including Les patineurs (1895), Beloved! (1906), Good-bye (1915), Thinking of You (1917) and The Crying Fox (1919). Rhodes Draayer suggests that the waltz Beloved! is even innovative in nature, and with it Worsley presaged the composer W.C. Handy, creator of such key pieces in the history of African American music as Saint Louis Blues and Memphis Blues. If we accept this researcher’s theory, the young Barcelona composer would have been a true pioneer of 20th century popular music. Or could it have been a coincidence? Perhaps. Some of Worsley’s compositions have a noticeable hint of ragtime. Others take listeners to the melancholy of the turn-of-the-century waltz.

Biblioteca Nacional de España

Covers to the sheet music of two of Astort’s Boston waltzes, edited in Barcelona.

Not all of Clifton Worsley’s works took the form of waltzes or other types of short, danceable compositions; rather, he also experimented with more substantial genres. In 1916, for example, the operetta Emma premiered at the Teatro de la Zarzuela in Madrid, with lyrics by Gonzalo Firpo and music by Worsley himself. Critics in the Spanish capital launched a savage attack on the work, up to the point of contemptuously labelling its creators as “Catalans”, as an article in La Vanguardia complained on 6 July 1916. “The genius of La Rambla de Catalunya must have been convinced that we Madrilenians would allow ourselves to be tricked by a poor Catalan peasant”, said one of the critics in Madrid, who defined the operetta as a “hideous monstrosity with all the worth of a slipper”.

Worsley had more luck with another operetta, El vals de los pájaros, a resounding success that premiered at the Tívoli theatre in Barcelona on 24 February 1917 and ran for several weeks. In what today we would call a preview, a journalist for La Vanguardia called Mariano Fuster drew attention to Clifton Worsley’s short pieces: “His endless waltzes, two-steps, fox-trots, etc., have made the rounds and continue to make the rounds triumphantly in all the sophisticated dance halls […] He has gained such popularity from them that the published versions would be enough on their own to have made their composer rich”. Fuster emphasises Astort’s good-natured and unassuming character: he “is a modest man, and it may be that his excessive modesty has stopped him from achieving the reward that fortune has wanted to give him on various occasions.”

Biblioteca Nacional de España

Covers to the sheet music of two of Astort’s Boston waltzes, edited in Barcelona.

After his death in 1925 Astort was gradually forgotten. Almost 50 years after his death, the journalist Pablo Vila San-Juan dedicated an article to him in La Vanguardia Española. Talking about the premiere in Barcelona of a comedy attributed to a foreign writer, Vila San-Juan used the example of Pere Astort as one of a writer that had to change his name to attain the fame he deserved. Vila San-Juan described a visit to Astort at his home where, according to the journalist, the Catalan composer had confessed to him that thanks to taking the alias Clifton Worsley he was able to enjoy the recognition that he would not have received as Pere Astort. This theory is at least debatable if we look at the comments from the press at the time.

From 1925 onwards, there have only been a few occasions when the name Clifton Worsley has come up. Jordi Pujol Baulenas cites Clifton Worsley’s danceable numbers in the introduction to his extraordinary monograph Jazz en Barcelona 1920-1965. On the other hand, the 2008 Festival Grec brought back some of his compositions in Xavier Albertí’s work Pinsans i caderneres, dedicated to turn-of-the-century Catalan music.