Doctor Jordi Sabater Pi’s most important contribution to science is related to the discovery of chimpanzee cultures. His studies and observations on this subject, published in the world’s most important scientific journals, have been decisive in changing the anthropocentric view of the universe.

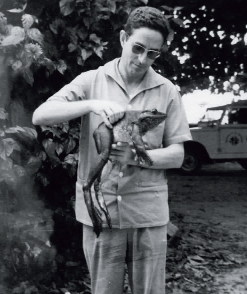

Of all the literary and scientific figures I have met in the course of my career as a journalist, Doctor Jordi Sabater Pi (Barcelona, 1922 – 2009) is one of the most fascinating. He attained worldwide fame in 1966 following the capture of the white gorilla, Snowflake, who immediately became the mascot of Barcelona Zoo, and shortly afterwards of the whole city.

Doctor Sabater Pi played a decisive role in this capture, as he himself explains very well in the autobiographical book Okorobikó. At that time he was head of the Animal Adaptation and Experimentation Centre of Ikunde, a village two kilometres away from Bata, the capital of Equatorial Guinea. The centre reported to the Barcelona City Council.

Sabater Pi had settled in what was then known as Spanish Guinea in 1940 – at the age of 18 –, fleeing from the aftermath of the Civil War, on the wings of a passion for Africa that had awakened in him during his student years at the French School in Barcelona. He reached Guinea totally destitute, and left it forever in April 1969, having become a world-renowned figure in the study of primates, just a few months after the country attained independence and when virtually the entire white colony was forced to flee.

Obligation and devotion

© Dani Codina

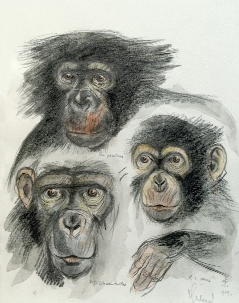

Drawing from the collection: the albino gorilla Snowflake at the Ikunde centre in Bata.

However, it should be mentioned that Sabater Pi’s social and professional ascent was by no means plain sailing. Lacking a university education, for many years he was forced to combine his job as a foreman on different plantations and agricultural enterprises with his passion for the flora and, particularly, the fauna of Africa. His initial field studies were published in several specialised foreign journals before they caught the eye of National Geographic, which, as everyone knows, is much more than a journal as it sponsors studies, awards grants, etc. At the same time he had made contact with the Barcelona Zoo, although the grant he obtained from the American journal raised more wary eyebrows among his superiors than benefits in his occupational situation.

In Guinea, meanwhile, Sabater Pi – not yet a doctor, and not even a graduate – was gradually managing to spend more time in the jungle than on the plantation. The presence of his wife, Núria, played a decisive role in this process. The couple had married in June 1950 by proxy; she in Igualada, and he in Equatorial Guinea. For some four years they had been writing to each other every day. Since communications between Guinea and mainland Spain were hardly daily, he used to send batches of letters to her and her father, in Igualada, would oversee them and give his daughter one each day.

In the professional scenario, 1950 was also a crucial year in the life of Sabater Pi. He began to observe primates, he made contact with some of the world’s leading ornithologists and he continued to learn Fang, the language that was spoken – and must still be spoken, except by for those who have been entirely Hispanicised or Frenchified – by the locals in Equatorial Guinea.

Primatology was born of the contributions of Darwin, who was the first to argue that primates form part of man’s evolutionary tree. In 1950, this science was still in its infancy given that systematic studies into primates did not actually begin until 1924. Sabater Pi lived far removed from the academic institutions that had begun to take an interest in primatology, albeit next to the jungles where the gorillas and chimpanzees dwelled. His mastery of Fang allowed him to strike up a very good relationship with the true natives of Equatorial Guinea, who from the very outset accompanied him as guides on his early explorations. Observing the gorillas meant long treks through the jungle, always following the indications of a local guide who was the best at interpreting the evasive trails left by the animals in order to get close to them. They used machetes to hack their way through and nightfall often took them by surprise, forcing them to construct makeshift beds (in the jungle, twilight literally does not exist).

Our man’s most important contribution to science is undoubtedly related to the discovery of chimpanzee cultures. Sabater Pi’s studies and observations on this subject, published in the world’s most important scientific journals, have been critical in changing the anthropocentric view of the universe.

Allow me to elaborate: what begins as a pure observation transforms into scientific truth when the observation is based on a method, continuity and rigour, and eventually delves fully into what we might call the meaning of life. Indeed, one of Doctor Sabater Pi’s obsessions, once he had secured undisputed academic recognition, was to fight the anthropocentric view of the world. For example, the idea of man as the son of God is related more to magic than to logic, because logic tells us that we are descendants of the primates and therefore form part of a biological ring; one that we should never underestimate if we really wish to understand human behaviour.

Naturally, this does not exclude any type of metaphysical belief, but is intended rather as a rallying call, we might say, to biological humility. We must never forget that mankind belongs to the great biological ring of the universe. Man, for example, is an animal who knows fear. Many anthropologists, as Sabater Pi explains, are of the opinion that the ideal size of human groups lies at the threshold of 500 people. If this number is surpassed, the individual begins to develop self-defence mechanisms such as suspicion or fear, which may become violent.

A late university student

After his return in 1969, Sabater Pi began his university studies. He was 48 years old, and for a spell he had to work in jobs outside of his specialty at Barcelona Zoo. He graduated in 1975 and began teaching at the University of Barcelona. In 1981 he got his PhD with his thesis entitled A comparative study of the chimpanzees and gorillas of Río Muni. It was at that time that he introduced ethology studies into Spain’s universities. Ethology is the biological study of human and animal behaviour from an evolutionary and descriptive standpoint.

Towards the end of his life, Doctor Sabater Pi received some of the highest Catalan and Spanish distinctions: honorary doctorates from the Autonomous Universities of Barcelona and Madrid, the Gold Medal for Scientific Merit from the Barcelona City Council and the Saint George Cross from the government of Catalonia. He passed away in August 2009 just after his 87th birthday. Some people, myself included, are sorry that he departed from this world without the gold medal of the government of Catalonia.