This year marks the centenary of three Barcelona-born writers who, although their lives ran in parallel, shaped by the tragic circumstances of the war, defeat and exile, are fundamentally different in their creative aspects. Barcelona does not feature prominently in the literary output of any of them, although the “great Catalan city” is nonetheless a character which “plays hide and seek” spontaneously in a number of writings (novels, short stories, poems, articles, memoirs and letters), laden in all cases with considerable autobiographical baggage.

Avel·lí Artís-Gener, Pere Calders and Joan Sales were all born in 1912 in Barcelona. Coincidentally, or not, all three went to the front, all three lost the war, all three were exiled, all three crossed the border at Col d’Ares, all three found themselves in concentration camps in Roussillon, all three sought refuge in the Americas, all three met up again in Mexico and, on returning, which they all decided to do at different times, all three once again settled in Barcelona, where they died: Sales in 1983, Calders in 1994 and Tísner in 2000.

Three parallel life journeys for three very different writers, all of them marked by the unique relationship they had with their home city and the different takes on the world that they developed and expressed in their writing, even though none of the three ever embarked on the magnum opus on Barcelona – an idea that emerged and lasted throughout the thirties, when all three writers were learning their trade. Nor did any of them intentionally make the city the protagonist of any of their novels, short stories, poems, newspaper articles, memoirs or letters, the preferred genres of all three. I say “intentionally” because unintentionally, the “great Catalan city” – the unnamed protagonist of Calders’ unfinished novel, La ciutat cansada [The Weary City] published in 2008 – is the character that plays hide and seek in all of his works, always carrying a piece of autobiographical baggage that can be glimpsed in the form of a memory, an anecdote, a setting, a character or, simply, some words.

Joan Sales, the least militant in his love of Barcelona, who once stated, “I am a native of Vallclara, born in Barcelona against my will”, began writing letters that, after many years, he compiled under the title Cartes a Màrius Torres [Letters to Màrius Torres], published in 1977, and set against the backdrop of a Republican, youthful, free and politically agitated city that, because of the anti-fascist reaction against the military coup of July 18th, 1936, adopts the features of Joan Maragall’s heroine from the famous Oda nova a Barcelona [New Ode to Barcelona], published in 1909. This is the underbelly of Barcelona: anarchistic, revolutionary and, according to Sales, the writer of this one-directional correspondence, a Spanish-speaking city of outsiders that embodies a form of anarchistic barbarism fighting against another form of barbarism: Fascism. It’s the “bad” city of Maragall’s ode, a city that has provoked another “tragic week” (long after the first “tragic week” of violent confrontation between the Army and the working classes in 1909). “Bad”, both for those who take action and for those who watch, paralysed with fear and who Sales, like Maragall, rebukes: “Whose fault is it that Barcelona has been burned at every corner? Ours: we have let it burn. It is our fault, nobody else’s” (2-8-1936). This then, is the “agitated”, “unhinged” city: the setting of a “macabre carnival”. But at the same time, it is the “enchantress”; the sensual city that is “delicately perverse on evenings that are under the double spell of a waxing moon and trees bursting with new leaves. The moonlight, filtering through the foliage, flatters the women of Barcelona and makes them look like young sorceresses. It is the revolution that has poured these subtle drops of deadly nightshade into city’s air […] With this revolution that rattles along, ‘shaking society to its foundations’, as the moralists would say, the girls have taken on an air of freedom that I find becomes them” (22-4-1937).

This is the Barcelona that Sales, married and with a daughter, renting a little flat at 36, Carrer Rosselló, would have wanted to see from the tower in Horta that so often appears in his letters and that became the ultimate viewpoint from which Trini, one of the protagonists of Incerta glòria [Uncertain Glory], ex-anarchist, classless and miraculously converted to Catholicism, watches the bombing of Barcelona while her husband, Lluís, and his friend Soleràs, fight on the Aragonese front, where they, between battles and during the many and long periods of inaction, reflect on good and evil, the human and the divine, life and death, pleasure and pain, synthesising the discourse against cultural identity that drives the novel, which Sales expresses in several letters to Màrius Torres, such as when he refers to the ideas of Acció Catalana, to “something as laughable as ‘a nation is a culture’” (2-2-1937) and how deluded poets such as Josep Carner and Carles Riba are, “who don’t know which world they’re living in”.

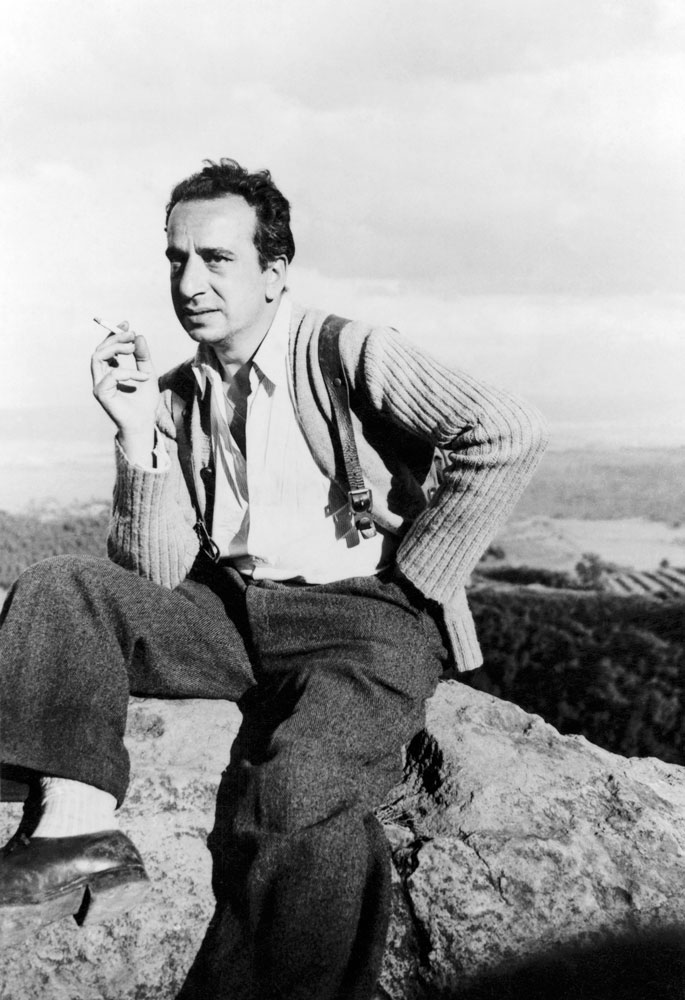

The implacable eyes of Calders

I do not believe that Sales included Pere Calders among these deluded souls, even if the Barcelona on which the author of Unitats de xoc [Shock Units, 1938] and Cròniques de la veritat oculta [Chronicles of the hidden truth, 1954] based his work was the same as that of Carner. In other words, it is a supposedly placid, civilised, almost always unnamed city that serves as a backdrop to the beings that populate Calder’s literary world. Lacking in common sense and in fear, such as the lad who is the hero of Carner’s short story La guerra [The War], they have no prejudices and they manage to cancel out the power of big words and reveal the inner workings of the stories on which the hidden reality is founded. Irony is the main narrative strategy used in Calders’ prose: it is the scalpel that dissects the images of the world that the reader, with his general leaning towards the obvious, automatically switches on.

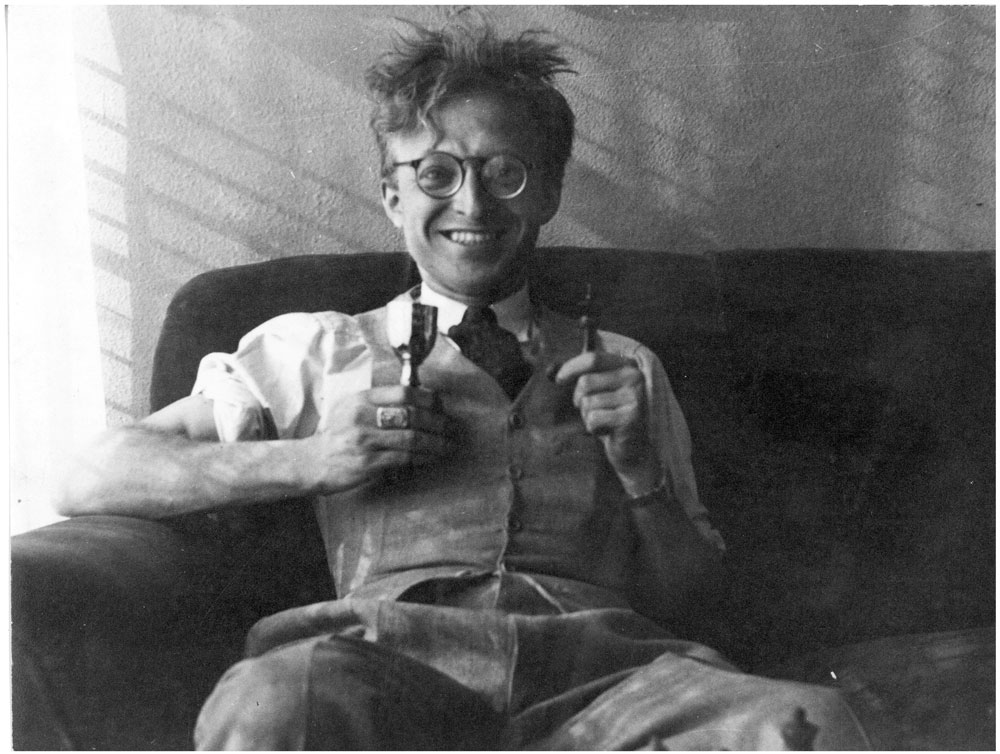

© Fons Pere Calders de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

Self-portrait of Pere Calders, chess trophies, of unknown date in 1947, in Mexico

So it is no surprise that, in a story such as El Desert [The Desert], the reader witnesses the transformation of a city from something really conventional with streets, houses, trees, aunties, fiancées, supervisors, doctors and envious friends into the desert that, metaphorically speaking, is the life of the character who feels his life eking away from him but is still in time to grab hold of it. Or, as in the recently published La ciutat cansada [The Weary City], the reader listens to the questioning of the six basic pillars on which a supposed “ideal city” is built. For Calders, then, the “underbelly” of the modern city is not made up of certain individuals or groups because of their gender, class or race. Rather, it is inseparable from the human condition and can be found inside every individual. It may look good-natured, but Calders’ take on reality and how it is represented is implacable.

And yet Pere Calders is in love with the city in which he was born and where he returned from exile to live, in 1962: “The thing with Barcelona is that, despite all the drawbacks it has, as does any large city, I love it. I can only speak well of it. I wouldn’t move […] This city is, above all, the capital of our country and I find it ridiculous that people are now talking about fighting against the so-called centralism of Barcelona […] We must not ignore the fact that it is very often in Barcelona that new things are born. If we ever gained independence or sovereignty, the country would need a nerve centre where the core services of the State would be concentrated”. These statements, published in one of the Diàlegs a Barcelona [Dialogues in Barcelona] between Joan Oliver and Pere Calders (1984) are a far cry from any attempt to mythologise the pre-war city, as is his affirmation (with an anti-sentimental distance not lacking in criticism of the policies of Franco’s dictatorship) that the only ones to be disappointed on their return were his children who in Mexico had imagined Barcelona as a kind of Disneyland and who found that, at least when it came to the weather, their parents had conned them.

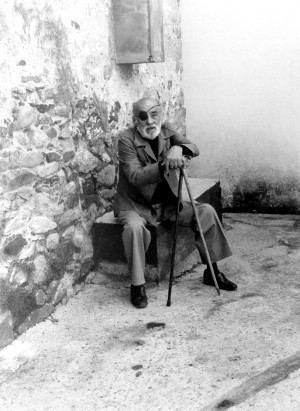

Tísner’s outlook is very different: he sees his arrival at the port of Barcelona on board the Satústregui as a reason to “go on a terrifying cave exploration inside yourself”, in other words, to “search for one’s roots” and to turn this search into the theme of one’s own writing. In reference to his first sighting of Barcelona from the sea, Tísner writes in the first volume of Viure i veure [Living and seeing] that “The geography now rearranges itself to fit the demands of memory: Montjuïc is now to the left of the picture and the city of Barcelona, your city, spreads out below the gentle, serene sierra of Collsarola, where every feature is neatly in its place like neatly aligned chess pieces: Sant Pere Màrtir, Puig Aguilar, Tibidabo, Vallvidrera, Collsarola and the hill of Valldaura, which is as far as my eyes and my memory can see. I would like to weigh up the twenty-six and a half years in which I have not laid eyes on my home city, but I am overcome by emotions that stop me from thinking clearly.”

It is December 31st, 1965 and “the taxi driver has good taste and is taking us up the Rambla […] They’ve changed my buses! They’ve taken away my trams! They’ve opened up new shops on me! They’ve tinged my city with a foreign tone! They did this to me while I was away! […] By dint of saying my city, I believed that the adjective did not signify affiliation, a simple demonym, but my physical and mental property. Getting used to the reality will be a long process: years will pass before I no longer feel like an exile, in an even more painful exile than the other one, and it will be a twofold process because at the same time I will have to get used to and accept that, if my city had not grown during the time I was away, it would mean that it had atrophied […] This disfigured Barcelona is, indeed, my city. I will find it once more among the trees that are gone, among the unknown faces and in the new streets. It will be a little hard because it doesn’t give itself away easily. On the contrary: it is elusive by nature and likes to play at hide and seek. But it is there: I will find it by dint of patience and unpleasant surprises and treacherous fears that it is no longer there.”

And in some way, this is one of the challenges of Tísner’s writing, especially his memoir: to rebuild a city that was mythologised in exile and that, now he’s back in Catalonia, has not completely lost that idealistic image. Tísner defends himself before anyone can reproach him. He writes: “Is exaggerating the same as lying? Any judge, however mediocre, would describe it as legitimate defence.” And it is in legitimate defence that Tísner seems to write when he devotes a considerable part of his literary work to resuscitating, through memory, the images of local customs, the anecdotes and the idealised pre-war Barcelona, which is not Sales’ Barcelona that has gone astray, nor Calders’ Barcelona of Noucentisme, but the Barcelona of Catalan Modernisme in the most popular and probably most colourful and picturesque sense of the word.

This explains why Tísner systematically reclaims the anecdotes of Modernista writers Rusiñol, Peius and Moraguetes (in whose wake Tísner follows) and recreates scenes from an old, typified Barcelona that is no more, even though he is well aware of mystifying the image of the city, as the author of a Guia inútil de Barcelona [Useless Guide to Barcelona] explains in Al cap de 26 anys [Twenty-Six Years Later, 1972]:

“In exile, one imperceptibly paints a perfect picture of one’s country […] One makes an uncontaminated and non-contaminable land, solidly built on an ancestral culture, which sets its own path that no-one can ever divert. Plenty of reasoning, well rooted in one’s subconscious, creates this formidable picture postcard, without realising that what one has really done is to stab in a paralysing injection from afar. We take a brief moment in our country’s history and magnify it to our liking, dressing it up as something eternal. It is not what we believe that counts but what we want to believe, what we need to believe, because we have to compare our portable picture with other, far too vain lands […] The fact is that during the long period of exile, one stops time when it comes to one’s homeland […] Beyond the ocean, and specifically in that little triangle you long for so hysterically, everything has stopped. Nothing will move until you get back. Put simply, you have fallen prey to absurdity. Ten thousand tonnes of involuntary self-centredness! And now, suddenly, the time has come to put this symbolic image right next to your actual country and compare it with the real thing. No more tricks, be they intentional or not. The analysis is despairingly cruel.”

Pingback: Torna Barcelona Metròpolis | Núvol