During his internal exile in Madrid, Agustí Calvet prepared two anthologies of articles written after the First World War, one on Catalan politics that was published recently, and another on Barcelona, still unpublished. These articles reveal a city turning from a provincial capital into a great metropolis.

I keep a strangely precise memory of that day, now more than fifteen years ago. At about half-past seven in the morning, as I did every morning during the last three years of my secondary-school studies, I got on the number 22 bus that went from Bonanova to the Escolapis in Carrer de la Diputació. I sat on the seats at the end of the aisle and out of my bag I took the compulsory book we were working on for the university entrance exam in the Catalan literature class, taught by the teacher Lluís Busquets. I finished Vida privada [Private Life] that day.

Although mine was the third stop on Passeig de Gràcia, if I had enough time I would get off at the Diagonal stop, just past Palau Robert, and I would walk to Diputació via the Rambla de Catalunya. I recall the smell of the lime trees in spring, especially if there had been a spot of rain, when almost nobody walked along the central part of the street and the ground was still a little wet. And the memory of those strolls is concentrated on the day I finished reading Josep Maria de Sagarra’s novel. Pilar Romaní has died at the house in Carrer Ample. Hortènsia Portell, a good friend, arrives in no time to dress the body and give some support to Bobby Xuclà, the grown-up son of the deceased. The narrator risks giving a lofty air to the feelings that the two actors in the scene are experiencing: “Only he and Hortènsia could understand the grace and beauty of an eighty-year-old body which, freezing little by little, was carrying away the sublime air of a long-gone Barcelona.”

Like Sagarra’s Memòries, maybe Vida privada has to be read as a splendid urban elegy dedicated to the end of a Barcelona age. Bobby walks down the street and heads for the Rambla: “Among the red roses there walked, a little unsteadily, a grey man of uncertain age with undefined cheeks, his stomach full of whisky and his heart full of red roses.” What causes a book to move us? Probably the very direct triggering ability of words, a part of our sensitivity that is predisposed to be shaken by an experience. And reading is an experience. I remember that spring day, when I was seventeen, because I contemplated the city with the mournful gaze through which Sagarra made Bobby Xuclà observe Barcelona while, with tears in my eyes, I walked down the Rambla de Catalunya.

Philosopher journalist

“I can perfectly remember, with that monotonous tone, as if I had just heard it, the advice we were given every summer morning, when we left home heading for the beach: ‘Don’t walk down the Rambla de Catalunya’…” This is the opening sentence of Una sombra, unos árboles [A shadow, some trees], the article which Agustí Calvet, Gaziel, published in La Vanguardia, page 10, on St George’s Day in 1919. It is brilliant. While describing the successive contemplation in time of the lime trees on Rambla de Catalunya, Gaziel, almost tempting costumbrismo, gradually reveals himself as what he essentially was: a philosopher journalist, in the words of J.S. de Montfort. The initial sentence of the article drew us back to the writer’s childhood. In the autumn of 1893, the Calvet and Pasqual married couple, who had become wealthy thanks to the cork industry, settled in Barcelona with their children. Until then, they had lived in Sant Feliu de Guíxols, the small port town from which both the mother’s and father’s families came. So Gaziel arrived in Barcelona at the age of six. Soon after he would hear the sentence he recalls to start writing Una sombra, unos árboles. “This avenue was then a never-ending straight line of sun. July’s burning bore straight down on it. Not a soul passed by.”

All the time the article contrasts old memories of the street with a walk that Gaziel had taken recently. “The passers-by paraded in the Sunday peace, under the relatively thick foliage. I remembered the sunny dryness of the avenue as if it was yesterday, and the current tender greenness gently surprised me, with a slight twinge of sadness. Were those the same squalid lime trees we had seen being planted? How could they now offer shade?”

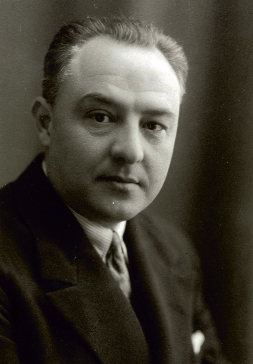

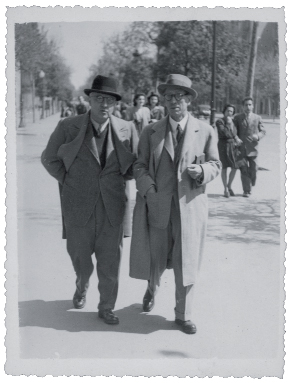

© Library of Catalonia. Graphics Unit. Gaziel Collection

Gaziel, on the left, strolling with the painter Joaquim Sunyer –“one of the best friends I have ever had” – along Avinguda Diagonal in Barcelona, April 1946.

The old heat had been softened by the present shadow. But the description of that urban change, caused by the growth of the trees, was only the specific subject of the article. The main point was the confirmation of how the changes in our city make us aware of our ageing. The subject, in short, was the passage of time. “Leaving our recovered home one spring morning, those lime trees we often forget surprise and charm us with their freshness, and quietly remind us that we are nearing the critical mezzo del camin: that with many ups and downs our life is slipping away, and that the yesterday of our childhood is separated from the today of our approaching maturity – like the dryness from this shade – by an irretrievable period of twenty years.”

Gaziel was thirty-two years old when he published Una sombra, unos árboles and he had become a very successful journalist thanks to the hundreds of reports he wrote from September 1914 on, explaining the First World War, most of which were very soon (between 1915 and 1918) compiled in four volumes published by the Estvdio publishing house. While Paris was his operations’ centre during his years as a war correspondent, on his return home, this prototype of 20th-century Catalanism who had matured under Prat de la Riba’s Mancomunitat [municipal commonwealth] became a leading columnist for La Vanguardia, the newspaper he would later edit.

Sharp political analyst

Among the profiles of that second Gaziel, that of a political analyst of the Catalonia and Spain of his time (the agony of the Restoration, the Primo de Rivera dictatorship and the Second Republic) stands out above all. But he did not only write about national politics. Not by a long chalk. During nearly twenty years he turned to other areas of journalism, offering a shrewd analysis of international politics, reporting on cultural affairs in Catalonia and writing about urban matters in Barcelona, one of his favourite subjects. I believe that because many years later, when he was living in internal exile in Madrid during the post-war Franco period and had been forced to abandon his profession some time before, he compiled all his work published in the press after the Great War, had it transcribed and, with that material, prepared an anthology with articles on Catalan politics (recently published under the title Tot s’ha perdut [All is lost]) and another on Barcelona, which still remains unpublished. The original, preserved in the Biblioteca de Catalunya’s Gaziel Collection, includes thirty articles published between 2 January 1919 and 2 June 1933, which the writer thoroughly revised (especially from a stylistic point of view).

The anthology shows an intellectual with a senatorial attitude who, as he intended with his political analysis, sought to guide, with considerable illustrated pride, a Barcelona middle class that, compared to Europe’s, he judged to be spiritually poor (it had been unable to produce its own newspaper in Catalan, for example, as he explains in one of the articles in La Vanguardia, maybe aimed at Francesc Cambó) and too closely linked to its working class origins (as shown, with some sarcasm, in the second of the anthology’s articles, La incómoda incomodidad, confirmation of the coarseness present in the theatre plays.

Gaziel, as the journalist Enric Juliana maintains, scolds people. He would tell them off, censure them and lecture them. In the articles about Barcelona, the intellectual Gaziel aimed to shape his reader’s feelings as residents of his city, and he sought to make them critically aware of some of the faults that Barcelona suffered. In that sense, there are two recurring topics in the anthology that led Gaziel to fight the authorities from his word pedestal. He criticised the City Council, attacking it more than once for its lack of thoroughness and planning when it came to redesigning Plaça de Catalunya. He dedicated four articles to this matter, the last one of which should have been published on 3 November 1927, but the censors prevented it (and he rescued it, with comments, five years later). Two days before, on Monday 1, Alfonso XIII had inaugurated the new square. The report of the ceremony, published in La Vanguardia, reproduced the conversation that had taken place that midday between the king and the Baron of Viver, the city’s mayor at the time:

“Actually, this project is good and it has the advantage over the previous one of allowing more free space. But has the Council,” asked the monarch, “signed any agreement regarding the architecture of the buildings in Plaça de Catalunya, in order to give it the necessary monumental character?”

“Sire, the Council is very concerned about this and is examining the issue.”

“Good,” answered the king. “But I believe there is also a project to build here, around Plaça de Catalunya, a building with a monumental character in which all the State services can be provided, services that cost Madrid’s public funds about four million pesetas.”

“Sire,” answered the Baron of Viver, “everything Your Majesty has just said is true. The State pays around two million pesetas for the rent of its services in Barcelona. And considering the importance of this amount, the Council agreed to erect the monumental building you referred to, pending a study.”

“With all these big public works,” said the king, “the general interest of the city must always be taken into consideration.”

© Frederic Ballell / AFB

Plaça de Catalunya in 1890, with the Panorama de Waterloo show building and cavalry troops patrolling.

I do not know how Gaziel got to learn about this conversation, but the off-the-record comments in them are not the most surprising thing. What is really odd is that all the arguments the king outlined to the mayor coincided, implicitly, with those defended time and again by the journalist in his articles, namely that the value of a square was to be found not so much in the square itself but in what surrounded it. Gaziel had criticised and would continue to criticise the fact that nobody had taken the trouble to establish some criteria for the buildings around Plaça de Catalunya and this meant that, contrary to the most beautiful squares in the world, the ensemble was characterised by an anarchic design. He had insisted so much, and his opinion was so respected, that the Council even set up a commission to study the case. But in the end, nothing came of it, and his final judgement could not be argued against: the square, he pronounced in 1927, was unfinished. And when, in 1932, he decided to revive that censored reflection, he went even further: “The square is worse than ever. Since then, some of its buildings have suffered mutilation, leaving them disgustingly beheaded for everyone to see. Others have been remodelled any-old-how. New squalid plots have appeared, without being built on. And the frame of the first Plaça de Catalunya offers an unbearable appearance of absolute anarchy, which I would venture to describe as broadly representative anarchy.”

The International Exhibition

The other subject over which he acted as an incisive intellectual, that is to say, as a free and reasoned critic of the established power, was linked to the International Exhibition held in Barcelona between 20 May 1929 and 15 January 1930. Some months after the inauguration, General Miguel Primo de Rivera had an article published, signed by him and dated in Barcelona, where he defended his government and economic policy. Faced with a chaotic past, he argued it was he who had managed to turn the country round and the best proof of his success was Barcelona:

“Barcelona, the city of revolutions and conspiracies, is today a model metropolis as regards its strong and well directed civic life, aware of its importance and influence, appalled by the idea of compromising the homeland’s present or future through mischief, clever tricks and excesses that would merely be despicable if they did not give weapons to Spain’s enemies and competitors, to harm its most vital interests and its worldwide prestige.”

Two days after its publication, Gaziel wrote the article “To Mr. Miguel Primo de Rivera, contributor to La Vanguardia”, in which he introduced himself as a “true Barcelona citizen” and asked the State to increase economic support for the exhibition. “You, my distinguished journalist colleague, who has so much influence among one and all, who rules everyone and almost everything, I am sure will inwardly say, with the solid intention of revealing it later in public acts, that Barcelona is right.” Even if the dictator believed it or not, the problem was that he only had just over three months left as head of the government. When the exhibition closed, Dámaso Berenguer was already the prime minister. Gaziel wrote an article that touched a raw nerve: behind the pomp witnessed on the newly developed Montjuïc mountain there was a huge debt, which ultimately would have to be assumed by Barcelona’s citizens. This burden was confirmed on 3 February 1931, via a decree endorsed in Madrid’s Palacio Real, stating that it would indeed be up to Barcelona’s citizens to pay. Gaziel, who was very critical, devoted two more articles to the subject. The first was entitled “Hemos perdido una guerra” [We have lost a war].

But neither the cost of the International Exhibition nor the criticism of Plaça de Catalunya’s redevelopment form the crux of this Barcelona anthology. There are other collateral threads, for example, the criticism of the type of urban development that was being carried out in contrast to Madrid, or the demand (put forward in the penultimate article, the one pruned the most for the anthology) that the authorities show a firm hand in dealing with the profusion of so many “social parasites”. Because “when there are no bombs, there are gunmen, and when there are no gunmen, then there are robberies, and sometimes, as now, bombs, gunmen and robberies all mixed up together”. What sets this collection apart is the stance Gaziel adopts towards his city’s evolution.

An unstoppable mutation

The philosopher journalist, a keen observer – in the Ortega sense – of what was happening around him, had the impression he was witnessing a definitive mutation of his city. The idea that he was immersed in an unstoppable change – linked to a change of civilisation – is the continuous undertone of the original, from the first article to the last.

The first, “La vitalidad de Barcelona” [Barcelona’s vitality], was published on 28 January 1928. Basically, it is built around the author’s thoughts after he read Un hiver a Majorque [A Winter in Majorca] by George Sand. The book, as its title indicates, describes the author’s stay in Majorca with Frédéric Chopin. They had gone there at the end of the 1840s, to help the musician’s recovery, but they soon decided to go back to France and, during the return trip, they stopped in Barcelona. These are the fragments that had an impact on the Francophile Gaziel and which he transcribes in his article.

What disturbs him is the confirmation of the profound transformation Barcelona had undergone during those years. “No trace is left of the walls, the drawbridges, the moats, the battlements, the sentinels, the terrifying gunshots at night, the rural forts, the gangs of bandits and Christian patrols. In the stillness of night, very relative in these times, the weary murmur of the sea can no longer be heard. Even the nightwatchmen have become silent.” And a little further on, in a fragment that he had erased from the newspaper article when he revised it for the anthology, he explains in detail what sort of city has been built on top of the one that has disappeared: “Nobody would recognise Jorge Sand’s provincial town in our aspiring metropolis. Barcelona has achieved its modern character: Barcelona is now the city of merchant banks and garages.”

The change from provincial capital to a metropolis: this, I think, is the theme of the anthology. A change that Gaziel does not wish to overlook but tries to explain by focusing on significant moments, detailing what disappears and what emerges – what links the city’s present with its past, thereby projecting itself forward – trying to put some sense and memory into it, so the new city might be more learned, richer and fuller, so it might become a city of bourgeois quality comparable to other European cities and which, in its modernising process, does not end up becoming a dehumanised megalopolis.

Preserving spiritual heritage

These were not exceptional thoughts in the Europe of his time. In October 1923 Gaziel gave a lecture entitled “Les viles espirituals” [Spiritual Towns] in Girona. Its theoretical basis was The Decline of the West, the most influential essay of the first half of the 20th century (in the words of Ferran Sáez). “Today we are,” he said that day, “the first to fleetingly shine Spengler’s light on the Catalan land. We have to admit that the first impression produced by this new light is sinister.”

The first part of Oswald Spengler’s book, published in 1918 and which Ortega had translated into Spanish before the French version came out, stated that European civilisation was heading for disaster. It was an unstoppable cycle. The masses lived on top of each other in the cities, with no moral energy and obsessed by money – “La ciudad de Mercurio” [The city of Mercury] Gaziel would refer to on 24 June 1927. But Catalonia, Gaziel claimed, would save itself if it introduced culture via second-tier towns that still preserved a genuine spirituality.

And it would also save itself if Barcelona managed to preserve a spiritual heritage under siege. This is what the article “Cancionero barcelonés”, published on 10 March 1920, is about. It praises the Catalan music-hall singer Pilar Alonso as an example of “the most local spontaneities of the arte menor [Spanish lyrical form]” that were being extinguished.

He speaks of it too in “Un voto por la barbarie” [A vote for barbarism], which appeared on 8 June 1921 and describes the installation of Planas Park in Les Planes, a leisure centre that disrupted the harmony of the woods in exchange for the “deafening din of the roller coasters, carousels, watching waves, target practice, electric pianos and huge strings of fireworks”. Gaziel saw it as an invitation to turn the public into sheep. “The only thing that matters is to stir up great masses, vast numbers of people, and keep them happy by stupefying them, so they cast their votes and spend their coppers. And nothing moves masses, inert or human, better than mechanisms, whether they are cranes or platforms for laughter.”

Nostalgia: the Sunday walk and the Sarrià train

© Josep Domínguez / AFB

The Via Augusta with the Les Tres Torres stop of the Railways of Catalonia line (now the FGC), in 1932. Gaziel nostalgically evokes the view of the sea from the train before the line was undergrounded.

In contrast to that, Gaziel highlighted in his articles typical Barcelona customs such as the Sunday walk. A tradition that had also evolved as a result of the city’s expansion. His grandfather had practised it after mass in the area round Carrer Ample. When he was little, he had seen him do it around Carrer Ferran, and going uptown, via Passeig de Gràcia to Diagonal. Cars, he sensed, would change that habit forever.

A certain nostalgia can be seen here for a purer world that is gradually disappearing. The mournful gaze appears here and there. For example, in “Un municipio que muere” [A dying town], where he recalls the day that Sarrià’s messenger sounded his trumpet and called the residents together to avoid their town being annexed by the big city. And especially in the colossal article “Pequeña elegía urbana” [Little urban elegy], secretly linked to the one just quoted because its specific subject is the description of the last trip Gaziel took on the Sarrià train. It “has, in mysterious ways, always been the centre of my life,” he wrote on 26 April 1929. “I have been travelling on it for about forty years.” This long experience as a traveller on the Ferrocarrils de Catalunya had given rise to a previous article, “Una franja de mar” [A stretch of sea]. In it, Gaziel described the prettiest areas of the city: Passeig de Gràcia, in winter; “under those beloved lime trees on the Rambla de Catalunya” in spring; round the narrow streets of the Cathedral in autumn. But for summer, nothing could be better than contemplating the sea along a stretch between the Les Tres Torres and La Bonanova stops. A picture which, with that line covered over, he would never be able to enjoy again. It was a spiritual loss for the city or, more accurately, the awareness of the passage of time in our spirit.

The philosopher journalist put it with the following priceless precision: “It is delightful to recall what the Sarrià train and the city of Barcelona were like forty years ago, but it is bitter to imagine that in another forty years we will know nothing more about them. Let the beloved city grow and prosper, as it is ours and we live in it. But, why can we not do the same? Its vitality somehow stuns our own, and every day it leaves us a bit further behind. In confirming its extraordinary changes, we inevitably feel that, in our brevity, everything we used to be in this huge municipal life is gradually being erased, and our own life is slowly becoming a picture of past times.” We jump from the specific subject to the generic. To an awareness of our own life because it is inseparable from its circumstances. According to Gaziel, the most heartfelt, what moves us as readers, was his Barcelona.