The technification of the classroom is utterly consistent with the most abject intellectual poverty. Teachers of Humanities should instil in their pupils the ability to face life’s challenges: teach them to think well as a prerequisite for living well.

For some time now I have been embroiled in the classrooms of lower and upper secondary school. I belong to the guild of philosophy teachers, and I am finding, all too often, that a considerable sector of my students, after a generally pleasurable sojourn into the limbo of secondary education, find the language of philosophy insurmountably opaque or are steadfastly resistant to it. Nevertheless, I do not attach too much importance to it or lose sleep over it. It is nothing new.

Since the reality of the classroom is wont to leave me somewhat groggy, I occasionally take the time to peruse the department’s administrative literature, particularly to ascertain what is required of me. And we have reached a point when you know not whether you are a nurse, a kindergarten monitor, a psychologist, a projectionist, a fireman, an acrobat or all of them rolled into one. As the Catalan Government Official Journal (DOGC no. 5183 – 27/7/2008) states, during compulsory secondary education “students will have the opportunity to discover the elements of democratic culture and will acquire civic values and attitudes consistent with coexistence”. Needless to say, this phrase, besides its cringe-inducing bureaucratese, is cynical in the extreme. However, we know well that reality is a completely different story. Many students reach upper secondary education lacking the faintest notions of reading and writing; their reading habits are, to put it mildly, lax, and in any event highly infrequent. Tweets, Facebook walls, sports articles and a half-read book by Jordi Sierra i Fabra cast away on a shelf would be a fair summary. The penyistes (“dontwannas”), as teacher Antoni Dalmases has dubbed them, yield even less. In this regard I would like to offer the reader some food for thought on the prevailing educational climate. And what concerns us, to put it simply, is chronic political mismanagement and pedagogical incompetence.

When we say that someone is competent, according to the Catalan Department of Education’s definition, what we actually mean is that they are fit, have developed the skills inherent to their profession, to their work, that they have mastered a technique; to wit, they know how to do their job. However, by introducing this term as an underpinning concept of our educational system, one takes an ideological decision, a decision which in actual fact seriously distorts our work. Nevertheless, this issue does not concern us here, but I will give you an example of this pedagogical tendency, which enshrines usefulness and competence, combined with a stouter-than-stout defence of technologism, in the form of an assertion I read in a newspaper recently. The utterance in question may be attributed to Woodie Flowers, Professor Emeritus of Mechanical Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, also the promoter of edX, a digital educational content platform that enjoys a certain advocacy among some educational lobbies in our country:

“The new technologies allow us to deliver high-quality training, with animations, embedded videos and other interactive and creative tools to make content more appealing. We still believe that classes in theory are the teachers’ domain, but Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie, and even Lady Gaga, could convey this content in a much more exciting way.”

If we stick to the local ecosystem, perhaps it would be better to drive the point home availing ourselves of celebrities of the ilk of Carles Puyol and Gerard Piqué, who are very popular with our adolescents. We are of the opinion that a hologram of such illustrious characters could perhaps accomplish, perfectly in keeping with the assertions of Professor Flowers, our work in the classroom, which has apparently become anachronistic, unglamorous and utterly dispensable, since, in Mr. Flowers’ opinion, we lack the panache to make it exciting enough.

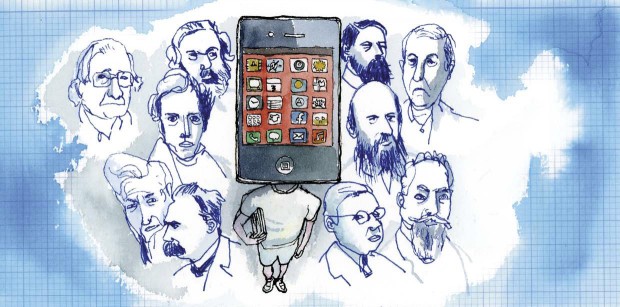

On the other hand, in a recent interview George Steiner said that his work as a teacher was about creating awareness in those that have learnt to read with him: “I’d love to be remembered as a good teacher of reading, and I mean remedial reading in a deeply moral sense: the reading should commit us to a vision, should engage our humanity…” As the philosopher Hans G. Gadamer wrote, understanding and interpreting texts patently leads to the human experience of the world, while also connecting with forms of experience (philosophy, art, history, poetry) that cannot be verified using the media available to scientific methodology, and are forms of experience in which, when all is said and done, science must acknowledge its limits. However, what most of our students’ parents expect from us might well be summarised in a comment at the foot of a news item, which addressed the current educational debacle: “The solution to our problems – it says – lies in more sophisticated human assets, capable of generating products and services with higher added value.” Of course. No mention of moral values, only “added value”. In this sense, it is our belief that the technification of the classroom, and the gobbledygook and conceptual confusion it has spawned (Aula 2.0, Pissarra Digital, eduCAT 1×1), is utterly consistent with, and rather multiplies, to the umpteenth power, the most profound intellectual poverty of our students who, as we teachers of humanities had also feared, have been abducted through an abyssal window where they are invited to dive into the laptop we have provided for them. We are not calling for a return to the times when the teacher’s word was cast in stone; quite the opposite. However, nor shall we side with those who would bury the teacher under a mess of cables and purportedly infallible technological gadgetry, as some technophiles now happily installed on the island of Bensalem seem to be advocating.

Reading has an increasingly marginal role in what is known as the knowledge society. In the picture, an infants class at Pere Vila School in Barcelona’s Sant Pere district.

Despite all this, some of us would like to maintain a space in which we can foster a critical, dissenting and dialogue-oriented spirit among our pupils. In a nutshell, we do our best to help them to live well. And living well only comes if you think well. All in all, and allow me to go somewhat Greek on you, all this ties in with Socrates’ famous therapeia tes psyches, i.e. the healing of the soul through knowledge. We therefore believe that our work cannot be reduced to the robot-like repetition of a handful of topics, totally devoid of any meaning, about citizenship and the values of a democratic system turned into a creature which governs us as best as it can, wilting away in its shabby and ragged garb. Quite the contrary: we should contribute, as best we can, to reviewing these concepts, now so perverted, to endow our students with sufficient power of discernment, particularly so that they can face the complexity of an increasingly denser and more augmented reality. I am saying all this because when you ask your lower secondary students to express themselves more concisely, and the ensuing reply is that enigmatic “Well I know what I mean”, you realise just how linguistically impoverished they are. But this “Well I know what I mean” issues from the mouth of one who fails to understand that, when all is said and done, without language they can say little about themselves, let alone about the world. And the world is overwhelming without a reasonable command of language.

We realise that we are addressing this issue at a critical moment, at a time when the figure of the secondary school teacher has been discredited to a seemingly irreversible extent. Ours is not a knowledge society, as some servile intellectuals would have us believe. In this frozen order of a present devoid of memory, reading plays a perfectly lateral, or even marginal role, one might say. The effects of this have been felt deeply by our adolescents, who are increasingly more incapable of concentrating in class or paying a modicum of attention to what we, the teachers, are trying to convey to them. Philosophy, understood as the memory of European heritage, should help to make our students’ thinking more fertile. But we do not know if there is still time. The cutbacks have only worsened the situation in the classroom. The Organic Law for the General Organisation of the Education System (LOGSE), the Organic Law of Education (LOE), Maragall, Wert, the psychomagic practitioners of education… Despite all our goodwill, sometimes you feel that the damage caused cannot be righted. However, as the wise philosopher said: “Do not weep; do not wax indignant. Understand.” We are determined to promote understanding.

Totalment d’acord. Tota aquesta invasió de màquines (ordinadors, tablets, etc…) és perfecta per a la propaganda política (“mireu, mireu com invertim diners en educació”) però totalment buida de continguts; són, al cap a i a la fi, joguines per a disfressar l’immens fracàs educatiu que patim.

Pingback: L’escola. De la crisi a la revolució | Núvol

Hola Albert,

Malgrat que les confessions d’una alumna aïllada tenen poc a fer amb la magnitud de la tragèdia que aquí exposes, arribada aquí (qui sap com) no vull deixar de dir-te que sis anys més tard encara recordo les teves classes, conservo els apunts de Filosofia I i algun examen, i fins i tot diria que em queda viva alguna de les neurones que vares estimular. Crec que no hi ha tablet ni ordinador que pugui substituir l’excitació al descobrir a Kafka o els primers intents d’escriure algunes reflexions amb cara i ulls (segons tu, amb un caire marcadament existencialista). En fi, significatiu o no, t’agraeixo altra vegada aquell curs que recordo encara ara amb tanta estima, i al que recorro de tant en tant quant de referents pedagògics es tracta.

ànims mestre, “que son pocos y cobardes”!