It is not polite to air a lady’s distress, so I will spare you the details of the night that Catalan philosophy went to A&E suffering from a panic attack. Nevertheless, given that it is a matter of national interest, I shall transcribe the conversation between her and the hospital psychologist, relying on your utmost discretion.

–Please take a seat, madam. I’ve just read the duty doctor’s report and am somewhat surprised. Have you never had psychological counselling?

–Please excuse me, doctor. But I didn’t dare to leave the house.

–There is no need to apologise, madam. Just make yourself comfortable and tell me what’s wrong.

–Actually, I find it hard to explain, doctor. The thing is that there are some days, a great many days in fact, when I feel, I feel that… I don’t exist. I think that I’m nothing, or at least that I’m nothing clear and distinct, perhaps merely a series of attempts that are always thwarted. Everyone knows what German and French philosophy is. But me? What am I? Am I the philosophy of the Principality of Catalonia? Of the Catalan countries? Of the territories of the former Crown of Aragon where Catalan is spoken? Do Catalans in exile count? Do 19th century Catalans who wrote in Spanish count? May I include jurists, poets and politicians rambling on about their ideology? What am I?

–Take it easy, madam, and express yourself calmly. There is no rush; philosophy and haste do not mix well.

–I know that. That is precisely what I have found so hard to understand and accept. Until about 30 years ago, when I realised that foreign philosophies had stolen a march on us in terms of output and dialogue between authors, I started to study their trends as if there were no tomorrow. I filled the Catalan universities with Heideggerians, Hegelians, Marxists, Neopositivists, Structuralists and so on because that was the order of the day. I took in all these philosophies, unsystematically and often uncritically. Excuse me, doctor. I just wanted to make up for lost time. Être à la pàge, comprenez-vous?

–Perfectly. But please stop apologising and tell me all about it, in order. How and when did you start to philosophise?

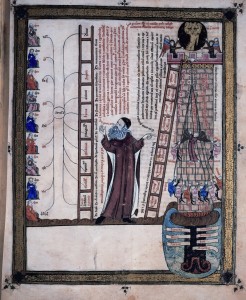

–Very well, doctor, excuse me. For many centuries, in Catalonia, like everywhere else, intellectual debate was a luxury reserved for the Church. The first active core was the monastery of Ripoll, built in the times of Wilfred the Hairy, although the truly important years began with James I of Aragon, three centuries later. I’m referring to Ramon de Penyafort and Ramon Martí, two Dominican monks and the king’s councillors, apologists and scholars of the scriptures and canon law, the former dedicated to converting Muslims and the latter to converting Jews. Nevertheless, James II of Majorca’s advisors –I mean Arnau de Vilanova and particularly Ramon Llull–, were much more ambitious, the latter regarded by many as the founder of Catalan philosophy. Llull had, well, a towering project: he wanted to systematise everything. He sought to explain, for example, faith through reason: this is why sometimes he seems to be a mystic and sometimes a scientist. Thanks to his defence of faith, Menéndez Pelayo regarded him as the origin of Spanish 16th-century mystics. And by virtue of his technique of attempting to examine the visible and the invisible by combining first notions, Leibniz identified him as the source of his Ars magna, a title which is a homage to Llull’s universal logic. Llull’s fame spread like wildfire, and in fact, from Pere Joan Llobet to Salvador Bové, from the 15th to the 20th century, he was the most widely studied Catalan and the one who left the greatest mark on my thinkers.

“I filled the university with foreign philosophies because that was the order of the day. I wanted to make up for lost time. ‘Être à la pàge’”

© Prisma

The representation of the symbol of the doctrine of Ramon Llull in a codex now kept in Baden Library, in Karlsruhe, Germany.

–Excuse me for interrupting, but are all your philosophers Christians? It’s important.

–Not at all. I don’t know if you’ve heard of Hasday Cresques, the rabbi of Barcelona who wrote, in 1397,The Refutation of Christian Dogmas?. However, he also discussed Maimonides’ reading of Aristotle and it is said that his thesis on emanation is crucial for understanding Spinoza. In any case, do not forget that in those days theology provided the framework for studying areas that are now independent, such as the philosophy of language. A few centuries were to elapse before we could move away from religion. In fact, this did not come to pass until the time of Peter IV of Aragon, who set up a kind of literary office inside the royal chancellery, where he had scribes translating works from Latin into Catalan. This MIT, so to speak, was consolidated in the times of John I of Aragon and Martin the Humane, and is where Bernat Metge worked, regarded by many as the reference point of Catalan humanism. In any event, the 14th and 15th-centuries also yielded two very important religious thinkers: Francesc Eiximenis and Raymond of Sabunde, whose Natural Theology delivers a very original reading of the two cities of St Augustine and St Bonaventure’s scale of creatures. Maybe you have heard of it: Montaigne translated the work into French and addressed certain aspects of it in his longest essay. The Inquisition prohibited Sabunde’s Theology, probably because it sees man as the first truth and appeals to his specific experience to reach God. I suppose they must have suspected that he was Averroist, albeit leaning more towards the side of reason, not unlike what happened to Joan Lluís Vives… You don’t happen to have a sweet, do you doctor?

–No, sorry, I don’t. But take a breather if you want. From what I can see your foundations are solid, which is crucial, because these are the formative years, when one’s personality is forged, which obviously makes any subsequent recovery much easier.

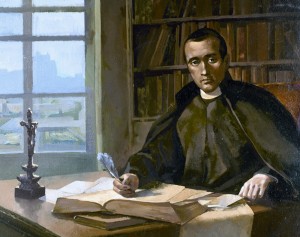

–I don’t know, doctor. The ensuing century was very difficult. In 1717, Philip V of Spain had all the Principality’s universities relocated to Cervera, and the University of Barcelona did not resume activity until 1838. He did so to avoid riots, because the lecturers and students of the capital had constituted a very active pro-Austria core. And that was a pity, because in the late 16th-century the university had six philosophy professorships and was much more open to the European Renaissance, whereas at Cervera basically Thomism and Suarezianism were studied. However, it did host some of the most renowned philosophers: Ramon Martí d’Eixalà, Manuel Milà i Fontanals and Jaume Balmes, of course. Haven’t you read El Criterio [The Criterion]? You should. Without it, it is impossible to understand, for example, the bishop Torres i Bages, who is also very important.

–So you had a very pious 19th-century? Is that a very painful memory?

–No, no. In fact, during those years my thinkers were heavily focused on cogitating about what we Catalans were as a nation. First Martí d’Eixalà, then Xavier Llorens i Barba and Manuel Duran i Bas formed what became known as the Catalan philosophy school, or the school of common sense, with a Scottish influence. Llorens i Barba formulated the national spirit theory, driven by an idea of philosophy as the highest expression of collective consciousness. According to Alexandre Galí, without his opening speech at the University of Barcelona for the 1854-1855 academic year, Prat de la Riba would never have formulated his political principles as he did. He is our Fichte, so to speak.

–And did this all take place in the proper setting; in the university, I mean?

–Not just there. It had a Faculty of Arts, although up until 1910 it only had a class in fundamental logic, which was given by Mr Josep Daurella. He was followed by Tomàs Carreras i Artau, professor of ethics, and Jaume Serra Húnter, professor of the history of philosophy, and in 1913 the higher psychology professorship was created, involving that famous competitive examination in which Cosme Parpal bested Eugeni d’Ors. The truth is that the university atmosphere was very grey, and would have been even more so had it not been for the seminars organised by Serra Húnter. I’m not surprised that Eugeni felt a tad uncomfortable in that environment. The thing about him was that he was always quickly stifled by any system. So he created his own philosophical programme with a language of its own. It is true that he sometimes talked about things he knew little about, but he did have talent, was ambitious and his work is at least exuberant. For some years Eugeni sat on the throne of Joan Maragall, who was not into philosophy proper, but thanks to the press and its praise he crafted an increasingly more refined thinking. His theory of love ties in with Raymond of Sabunde’s. And the romantically tinged “living word”, which Francesc Pujols thought he would take over from… Are you laughing? If you are going to mock Pujols I’m out of here. I’m fed up of seeing him scorned. Or are you of the opinion that you are not a philosopher unless you write like Eduardo Nicol and Josep Ferrater Móra?

–I was not laughing, madam. But anyway, calm down, as I think that we’ve had enough for today. For the next session, first of all I would ask you to stop apologising: forget your hang-ups. Then please make an honest list of the authors you believe have been unfairly ignored and those who have been overrated, as the case may be. And finally, tell me which living thinkers can help you to grow.