Each Barcelona passageway is a different world, in its origin, current use, location and shape. Below we underline the uniqueness of these access routes using ten diverse examples from different districts in the city.

What exactly is a passageway? What is its function? Traditionally they were considered to be shortcuts connecting two streets, but they can also be dead ends. Some are purely residential, majestic or common, but others have become true commercial hubs; they cross parks and gardens and break the urban sprawl; may be paved or lack any kind of surfacing, open to traffic or not, have trees or be vegetative wastelands.

Some are practically invisible, others hide inside neighbourhood doorways, and there are even those that do not exist despite having been given names.

As far as urban typology goes, in the Dreta de l’Eixample they break the regularity of Ildefons Cerdà’s design and cross the blocks horizontally or vertically; in Sagrada Família and Poblenou we find them resulting from the best use of space in industrial land; they are diagonal, zigzags, T-or L-shaped, separate houses from gardens and are even made up of steps.

In the ten districts of the city, we have tried to choose examples that illustrate the various types and their uniqueness.

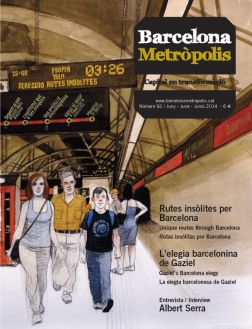

© Albert Armengol

Passatge de la Cadena, in the vicinity of the Estació de França, and the passageway accessible from number 29.

The Cadena in Ciutat Vella

It is necessary to get to the inner terrace of the Bitácora restaurant to discover the ancient Cadena passageway, which still has its signage. It was located near the Estació de França station and had a chain across it due to its proximity to the train line to Mataró.

It marked the northern limit of Barceloneta, was made of sand, and was oriented diagonally, leading directly towards Torín, the city’s first bullring, opened in 1834 and which was in use up until 1923. The Mas dels Arcs shop, on Carrer Balboa, 13, also recalls it, since the store is located on a stretch of the alley.

Eleven little white houses in the Eixample

If you cross the stairwell of the flats at number 29 Carrer de Rocafort, you will be surprised to find yourself in the middle of this urban delight made up of eleven single-storey white houses with roof terraces, built around an unnamed interior passageway that is not found on any map or in any guidebook.

It is made up of two narrow streets filled with the residents’ plants. They are 35 m2 dwellings that have a little covered yard in the rear – the original site of the latrines – with a staircase going up to the roof. In 1924, the owner asked the City Council for planning permission. It is possible that they were housing for the people working on the 1929 International Exposition.

Ministral, enchanting in Gràcia

A large, curved portal announces the charming Ministral passage, set on private land, in the Coll neighbourhood. It takes its name from the land’s owner since 1922. The construction of the 25 houses is very unusual and original, as it overcomes the steep slope with three different levels and the houses have ventilating skylights.

It is said that the buildings were the homes of construction workers, many from the quarry in the Creueta del Coll hill, and that during the Civil War, the deepest part served as a shelter for a group of anarchists.

Horta-Guinardó: the surprising Dipòsit

In the highest part of the Can Baró neighbourhood there is the surprising Dipòsit passage, comprising a stairway with 248 steps on a steep incline. At the top is a fantastic vantage point overlooking both the urban landscape and the sea.

We can see the old circular tank, situated at a height of 95 m, which lends its name to the place. It was built in 1870, after the expropriation of the land from the Can Baró estate by the Societat General d’Aigües de Barcelona, a Belgian company founded in Liege in 1867.

The English neighbourhood in Les Corts

The Tubella passage makes reference to the name of the merchant who developed the area from 1925 onwards. Twenty-two two-storey family homes were built there, on either side of the road, with small, gated front gardens and interior patios. We should point out the style, which includes a mix of Modernisme and Noucentisme influences, and their different colours. They are very well preserved and, with the exception of two newly constructed blocks, make up a stylistically harmonious unit.

Created to provide housing for English technicians who had to work in Joan Tubella’s textile factory, they were ultimately sold to the skilled workers from the industries in Les Corts and Sants.

Esperança in Nou Barris

On the eastern side of Plaça del Virrei Amat is the Esperança passage, made up of 15 terraced family houses that date back to 1927. They are single storey with a ground floor and a backyard, Noucentisme in style. All follow the same architectural type, with small variations.

The passage was developed as an initiative of the Sociedad Cooperativa de Cargadores y Descargadores de Algodón, the cotton handlers’ association. Like other professional bodies, the Society welcomed the laws brought in during the Primo de Rivera dictatorship which encouraged the building of affordable housing to alleviate the shortage of housing.

Sant Andreu: magnolia passage

In the Navas neighbourhood, between Olesa and Juan de Garay streets, is the calm Artemis passage, wall-to-wall with magnolias. Here is a relatively uniform set of dwellings, built around 1932, that follow the same pattern of semi-basement, main floor and balconied first floor, and backyard.

The name refers to the Greek goddess of hunting and nature, twin sister of Apollo, and a symbol of virginal beauty, often represented holding a golden bow and arrow. A section of the old Guineu watercourse, after which the Guinardó area is named and which rose from the communal Cuento spring, crosses this passageway.

© Albert Armengol

Robacols, in the Clot district, accessible from number 37, Carrer de Rossend Bobas.

Sant Martí: rural remnants

Through the large entryway into number 37 on Carrer de Rossend Nobas, in the Clot neighbourhood, you reach the curious Robacols passage, a clear example of the last vestiges of rural Barcelona and one of the most simple specimens of popular architecture. Although it is mostly abandoned, there are still nine terraced houses, with a ground floor and upper storey, all located on the right of the passageway; on the other side are the remains of former yards, previously gardens or for growing vegetables, now overgrown and full of junk.

The passage was developed in the second third of the 19th century and the houses were for local workers. The name “cabbage stealer” comes from the popular nickname for the Casas family, who owned a lot of land in Clot and Camp de l’Arpa.

Sants-Montjuïc: the Bordeta corridor

To solve the 19th-century housing shortage, it was typical to build houses along very narrow alleyways, the so-called pasillos, or corridors. One of the last-surviving examples in the city is in Bordeta, on Carrer de Bartomeu Pi, named after the old leather manufacturer who owned the land.

The passageway is unnamed and comprises ten very simple houses, of around 30 m2, that were constructed between 1925 and 1930 in the stables and fodder stores of an old factory.

© Albert Armengol

The small Mallofré road, connecting Major de Sarrià and Carrer del Clos de Sant Francesc.

The Sarrià-Sant Gervasi shortcut

The little, semi-covered Mallofré alleyway, open between 1866 and 1870, connects Major de Sarrià and Clos de Sant Francesc streets. It is named after the trader Josep Mallofré i Trius, who bought the land occupied by a former barracks, and which was used as a car park by a transport company.

After demolishing the existing buildings he built three houses: one on Carrer Major, one on Clos de Sant Francesc, and the other in the interior, in such a way that they formed a passageway that was also used as a shortcut between the two main streets.