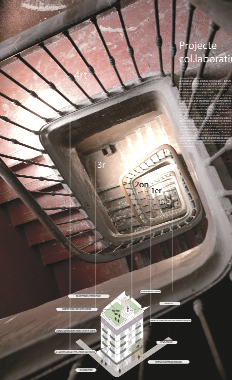

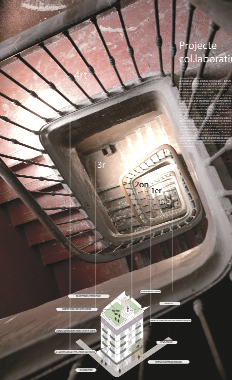

A meeting of participants in the La Borda cooperative project, at Can Batlló.

Cristina Gamboa / La Borda

It’s time to start cooking. Let’s mix some cooperative approaches with views on gender and typological experiments, social policies with legal opportunities, and environmental awareness with countercultural and anti-regulatory efforts.

We have a housing problem. It concerns the right to housing. Buying a house is the most important investment we ever make. It uses up most of what we earn. Housing is essential to our identity because the home provides a shelter for our other rights: if I’m not registered as a resident, I can’t vote; if I don’t have anywhere to shower I can’t look for work; if I don’t have a place to sleep, how can I possibly establish relationships? If houses are just goods, how are housing rights possible? How can we even contemplate our right to the city?

We have a problem regarding the lack of transparency and accuracy of information on housing. Houses and our ability to fall into debt by buying one is one of the main measures of the country’s wealth and national solvency. Housing is the new gold standard. The information we dispose of is contradictory and scarce. Moreover, the data we do have is devastating.

The cooperative Sostre Civic program, at Carrer Princesa 49.

Foto: Jordi Gómez / Adriana Mas

A third of families in Barcelona live in rented accommodation and two thirds are homeowners, but almost all of these properties are on the free market. Social housing constitutes less than 1.6%. This would not be a problem if the market were self-regulating and it covered citizens’ needs, but the economic crisis has shown that the market only regulates in favour of the wealthiest members of society. Moreover, when the market is at its greediest, this 1.6% proves inadequate in meeting the requirements of those who have been pushed out of the market.

In short, more than half a million people have been evicted in Spain since 2008. It represents the Spanish equivalent to the 5 million people who were evicted as a result of the American subprime crisis. Among all Spanish cities, Barcelona is home to the most evictees, and the neighbourhood with the most evictees is Ciutat Meridiana. Half a million is a lot of people with their bags piled up on the pavement, equating to the size of the largest Spanish provincial capitals. They represent 500,000 units of pain and despair: 500,000 units of anguish who have lost the will to live. We have a housing problem, with our social services up to their ears because State welfare arrives late, if at all. Our healthcare services have collapsed, with an influx of illnesses linked to the lack of housing and mental health conditions brought on by fear. And this is the same healthcare system that is undergoing cuts and privatisation.

We have a housing problem in Barcelona because there are 3,000 people sleeping rough whose only place to turn to is a volunteer-run and insufficient shelter network. It should not be this way. Barcelona is a wealthy city.

We have a serious housing problem because what was meant to be a refuge has turned into a shipwreck.

The local authorities, so quick to launch big schemes, have proved to be sluggish in their attempts to solve the problem. Both the media and political neglect are responsible. Years of rhetoric from boards, desks, observatories, committees, departments, directorates, drives, councils, offices and even ministries – which there have been – devoted to housing. There is not much rice and it has been stirred. Stirred rice is spoiled rice.

But all is not lost. There are five different areas of housing proposals that offer solutions. Firstly, there are proposals from the solidarity economy. Two experiments are underway in Barcelona: La Borda and Sostre Cívic, at Can Batlló and on Carrer de la Princesa, respectively. They propose the cession of use cooperative model as a housing solution that will allow people to settle, i.e. enrol their children in school or change their bathroom tiles, without unleashing the little speculator we all have inside us. This is no invention. The Andel cooperative model has been proven in Scandinavia, with ratios of up to 30% of the housing stock (Copenhagen). You might think this is a solution for the wealthiest countries. Well, it is not. In Montevideo, Uruguay, the model has been applied with a rate of 4%.

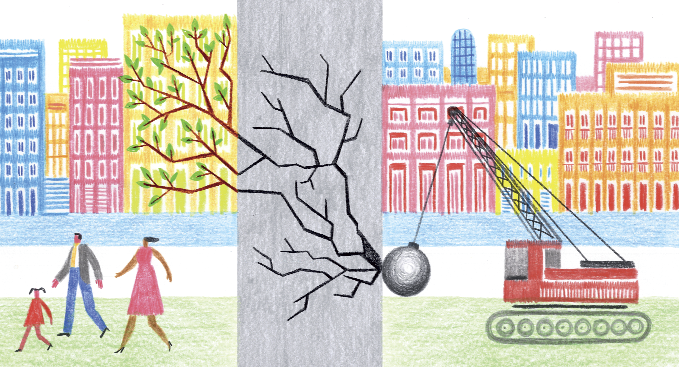

A squatted building.

We have grassroots and counterculture proposals. The okupa squatter movement, spelt with a “k”, is a political phenomenon in response to an abusive market and it has been violently repressed in Spain. It would be impossible to conceive experiments such as London’s Bonnington Square or Copenhagen’s Christiania in Catalonia because the repressive mechanisms of local authorities are merciless. Spanish legislation places private property rights above other rights that affect the masses. In spite of all this, fortunately, the okupa and self-management housing collectives denounce speculators with their actions, as well as those who look down on and neglect their city and neighbours.

The Arrels Foundation’s Pis Zero project.

Moreover, there are proposals regarding social policies. The Arrels Foundation’s “Pis Zero” (Zero Apartment) offers a response to the reality faced by long-term street dwellers which overcomes the confines of only relatively effective welfare mechanisms. The “Arquitectes de Capçalera” initiative recovers the architect’s social role through a professional call to arms in response to emergency situations. These proposals go beyond the American Housing First approach, which has also been adopted in Australia, France, Canada and Finland.

There are also proposals regarding sustainability and materials. Building with sustainable materials and holding workshops on the energy usage and maintenance of buildings provide strategies for fighting fuel poverty. The 2014 International Solar Decathlon award marked a turning point in the way in which housing is thought about in terms of its most important function: to provide actual shelter. The most interesting aspect of the competition’s most recent edition is not the winning piece’s technological capacity to be built and to function with virtually no environmental footprint, which it does. The best part is that it directly criticises the idea of a detached single family home as a model of urban growth. Single family homes are incompatible with the idea of a sustainable city. The Vallès School of Architecture (ETSAV) submitted the Ressò project, which won the first prize for innovation with a solar community house for social rehabilitation.

Image from the Vallès School of Architecture (ETSAV)’s Ressò sustainable community architecture project, the winner of the innovation prize in the 2014 international Solar Decathlon.

Foto: Sandra Prat

Lastly, we have proposals based on architectural form. France has moved ahead with densification projects in its suburban housing estates. It is no coincidence that housing initiatives coexist alongside an economic experiment within the one culture that has proposed theoretical alternatives to savage capitalism with the most editorial success. The essays published by _Export Barcelona on new residential architecture are extremely useful for moving forward. The “Casa sense Gènere” (Gender-Neutral House), a product of avant-garde feminist architecture, demonstrates the deceptive rationale of modern typologies. Designed by and for men, hierarchal spatial distributions actively disregard household chores through narrow, out-of-the-way kitchens that require women to work with their backs turned to their families, and tiny laundry rooms that are incompatible with domestic harmony. The Rehabitar research team reminds us of the benefits of a thick, mixed urban fabric and, like the feminist architects, demands housing that promotes equality and enables the home to adapt to changes in the family dynamic that occur over time.

Image from the Vallès School of Architecture (ETSAV)’s Ressò sustainable community architecture project, the winner of the innovation prize in the 2014 international Solar Decathlon.

Foto: Sandra Prat

The five different proposals could lead to a city project that overcomes the housing dystopia with real, proven situations. Not one of them falls into the “smart city” trap, which is the town planning equivalent of using deodorant without showering. They are five consistent ingredients, constituting sustenance, not cosmetics. These are the five projects that bind the rice to the bottom of the paella.

There are different interpretations regarding the etymological meaning of the word paella. The majority point to the Latin word patella, which describes a pan with two handles. Some defend its Valencian origin: from the Catalan words plat, platell and platella. In old and Latin American Spanish there is also the word paila, which is a large and fairly shallow metal pot.

However, the hypothesis that best suits the purpose of this article upholds that the origin of paella is baqiyah, an Arabic word meaning “food leftover from the day before”. It is the most suitable theory because it steps away from the idea of the container and focuses on its contents. The contents are the leftovers, what is there. At home, food is not discarded – people make the most of what they have. The same thing should happen in the city, which is everybody’s home. The city of the future has already been built: this is it.

Let’s not overcook the rice

The Torre Via Júlia social housing project, included in the “Export Barcelona. Social housing in context” travelling exhibit, which includes twenty social proposals by Catalan architects.

This exhibit is one of the invents included in the second edition of the Cities

Connection Project.

Foto: Vicente Zambrano

It’s time to start cooking. Let’s mix some cooperative approaches with views on gender and typological experiments, social policies with legal opportunities, and environmental awareness with countercultural and anti-regulatory efforts. Urban planning has an inherent ability to bring these mixtures together and turn them into reality. However, doing so requires clear political will and a perspective capable of confronting important matters without abandoning urgent ones. To start with, projects should be carried out on a limited number of well-chosen sites. Approaching public housing policies solely on the basis of quantitative welfare logic is unrealistic. The location within the city is key, and harmony between the housing and the public space, absolutely vital.

The idea is to generate small-scale social housing and rented accommodation, in developments of two, four and twelve units, on sites that make the most of the city as it is now, by following the logic of the three Vs: value, visibility and viability. These places of opportunity exist within the compact city: narrow buildings against solid dividing walls; height extensions to existing constructions that rush through planning permission; and interstitial housing units. It is a question of taking advantage of scuffs in the urban fabric and being in contact with infrastructures. Moreover, there are places of opportunity along coastlines and riverbanks, as well as existing roads.

It also involves making the most of a productive framework that has been crippled by the economic crisis: small developers, construction-based trades, the 50% youth unemployment rate.

Can Caralleu social housing project, included in the “Export Barcelona. Social housing in context” travelling exhibit, which includes twenty social proposals by Catalan architects.

Foto: Vicente Zambrano

It’s about making more with less, on an experimental basis, so that constraints and legislative contradictions may be overcome. The elements must fit in with the existing neighbourhoods and encourage income diversity through a variety of types of homes, as well as different prices and access mechanisms to suit the incomes and life plans of their occupiers.

The idea is to start by organising joint binding tenders with equal conditions for small businesses, in which it is imperative that older professionals work alongside young people. They have to be a sum of tenders, the reward for which is coordinated implementation, which overcome the conventional “competitiveness” and “excellence” formula in favour of collaboration and diverse disciplines.

By doing it this way, adopting the strategy of an urban orthodontics team that is going to fill, restore and salvage units or fit a “crown” or “implant” at most, we will be able to go about creating a social housing stock of rental properties that can mitigate the extremes of the market. Anything else is like a set of dentures against the delicate natural landscape surrounding the city.

We have put in too many shellfish. Paellas shouldn’t have so many molluscs. That would be a seafood platter. Our dentures have gotten caught on the leg of a lobster. We need to add more rice. And we cannot just add it around the edges like a side of boiled rice. The rice absorbs the flavour of the ingredients from the depths of the paella and distributes it between the diners. That is where its democratic power lies.

Can Travi social housing project, included in the “Export Barcelona. Social housing in context” travelling exhibit, which includes twenty social proposals by Catalan architects.

Foto: Vicente Zambrano