A sword of Damocles hangs over the head of today’s generations: the deterioration of the environment and climate change. The impact on human health of all this environmental turbulence also has enormous costs: economic factors must not serve as an excuse to postpone the necessary protection measures; in fact, quite the contrary.

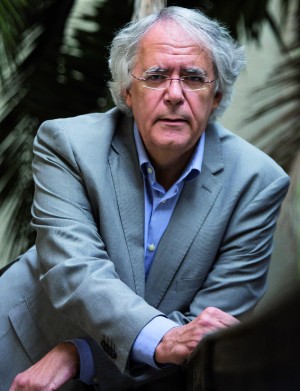

Doctor Josep Maria Antó (Cornellà de Llobregat, 1952) works in the field of respiratory health and the environmental factors that affect it. Having graduated in Medicine from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona in 1975 and completed his Ph.D. in 1990, Antó switched to epidemiology in the 1980s. As Head of Epidemiology and Public Health at what is now the Hospital del Mar Institute for Medical Research (IMIM), which he joined in 1987, he played a leading role, alongside Doctor Jordi Sunyer, in the discovery of the link between the unloading of soya bean at the port of Barcelona and the epidemics of acute asthma that had already been getting media coverage for a few years. The epidemic ceased when they put the appropriate filters on the silos where the crop was stored.

Since then, he has continued to conduct research in this area and created a training centre at the Environmental Epidemiology Research Centre (CREAL), which he led and which merged with the Barcelona Institute of Global Health (ISGlobal) in June to form one of Europe’s largest health research centres. He is currently the Director of Science for this organisation, a role that he combines with teaching at the Universitat Pompeu Fabra (UPF), where he is a Professor of Medicine. In September, he gave a talk on climate change and its impact on health as part of the “Futur(s)” lecture series organised by the Ateneu Barcelonès and the Social Observatory of “La Caixa” bank.

What is the impact of climate change on health?

The most obvious one is heatwaves. For the last 30 years we have seen evidence that when we have a run of hot days, the mortality rate increases. The heatwave of August 2003 in Europe caused 20,000 more deaths than usual (15,000 in France and 3,000 in Spain). Similarly, we know that mortality also increases with cold weather. We must also take into account the consequences of extreme weather events, such as flooding and fires, that create particle pollution. In other words, there is a second line of indirect effects, because the climate has a multiplying effect on common problems.

We’re not talking about future risks but rather about very present ones, right?

Around the world, about seven million people die who would otherwise live if air pollution were to remain at the levels accepted by the World Health Organisation (WHO). Sixty per cent of this pollution is caused by road traffic. Climate change brings a rise in temperatures and possibly a rise in episodes of air stagnation. When the two phenomena coincide, their effects multiply each other. Another example is the diseases transmitted by vectors such as the mosquito. Climate change affects the geographical distribution of these vectors and this may also lead to changes in the distribution of disease, as is the case with malaria and dengue fever.

Can climate change have other unexpected effects on our health?

The most worrying are the systemic and complex effects about which we are not yet aware. For example, what impact climate change has on biodiversity, on the array of animal and plant species that are around us and with which we coexist. In my field, we are seeing more and more evidence of the impact of climate change on the number of plant species and bacteria (the microbiome). This biological diversity influences our immune system. Because they are such complex systems, even a small change can have disproportionate effects. There is evidence – albeit still incipient – that with less biodiversity the rate of asthma is higher. Another type of very important, complex effect is that of species migration.

And yet the emissions cuts that we need are still not being applied.

Our generation is living with a sword of Damocles hanging over our heads and we need to take urgent measures. The international agreement made at the Paris Climate Summit (COP21) is a first important step in the reduction of emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases. But it is still difficult to predict what its scope will be.

The economic cost of these measures tends to be used as the main argument against them. How can one persuade society that protecting the environment is also positive from an economic perspective?

The impact of climate change on health has astronomical costs in terms of GDP. Policies that protect the environment generate wealth because they save lives and because they remove some of the burden on the health system. We need to think of the environment as another economic factor. In addition, an environmentally sustainable economy can create new types of products and services and generate wealth.

In recent years, there has been an increase in the incidence of respiratory illnesses. According to WHO forecasts, cancer rates could increase by 75 per cent by the year 2030.

That’s right, and cardiovascular and mental illnesses and allergies have increased too. In general, the frequency of chronic diseases has risen. Why is this? On the one hand, our life expectancy is growing, but we are at greater risk of getting ill because many of these illnesses are linked to ageing. But there are multiple reasons for this increase in disease, including environmental ones. For example, in the field of respiratory diseases we have seen a substantial increase in the incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which was quite rare 30 years ago. This increase is clearly linked to smoking. We also know that air pollution increases the risk of serious episodes and of death in COPD patients. When it comes to the higher incidence of chronic diseases, we know where we’re going wrong: an unbalanced diet that’s too high in calories, smoking, an increasingly sedentary lifestyle and, in particular, social inequalities, which constitute the underlying structural cause.

Are the areas that have more polluted air also the ones with the worst health?

One can often not establish geographical patterns for a single cause of a disease. For example, in Spain there is a clear pattern of death from bladder cancer, with greater incidence in some areas of Andalusia and Catalonia, where there has been industrial and mining activity. The increased mortality from bladder cancer in areas of El Vallès strongly suggests a correlation with the presence of the textile industry. Another very clear example is the increase in cases of cancer – such as mesothelioma – that are related to workplace or environmental exposure to asbestos. In Barcelona, there is a clear, indisputable pattern, and it’s to do with social inequality. The difference in life expectancy between the wealthier neighbourhoods and the poorest ones is ten years, a fact that explains the majority of diseases. In the poorest neighbourhoods, the housing, nutrition and working conditions are worse; there is more stress about life, people smoke more, and so on. In Sarrià, Sant Gervasi or Pedralbes, people live longer than in Ciutat Vella. This is a common phenomenon seen in all cities.

And are poorer neighbourhoods also more exposed to pollution?

No, in Barcelona air pollution from traffic is no worse in the poor neighbourhoods. There are neighbourhoods with high purchasing power and a lot of traffic, where people are clearly more exposed to pollution and where there may be even more noise. The market may not have internalised this yet, but it will eventually.

Do we often exceed the thresholds of admissible air pollution?

There are two important thresholds: one is based on health criteria and is set by the WHO, which we exceed by a long shot, and the other is the legal threshold set by the European Union, which is more lax, putting economic and political criteria ahead of health.

Is there a correlation between pollution and hospital emergency cases?

Hundreds of studies demonstrate that the more air pollution there is, the more health problems there are. Reducing pollution by 20 per cent would prevent 2.8 per cent of deaths and emergency admissions for respiratory and cardiovascular cases, according to studies our centre has conducted. We have even seen an increase in hospital admissions on days when the levels of pollution were below WHO guidelines, so these recommendations are also questionable. No matter how little pollution there is, it still has effects. And although individually those effects may be small, when they accumulate in areas with millions of people, they have a big impact.

How many deaths could be avoided if air quality were improved?

A 2007 study by CREAL showed that in the metropolitan area of Barcelona particle pollution could be attributed to the premature deaths of 3,500 people over the age of thirty each year. In one of our more recent studies, Professor Mark Nieuwenhuijsen examined the relationship between deaths and the following five factors: exposure to air pollution, sedentary lifestyle, noise, heat and the lack of green spaces. Barcelona could prevent up to 20 per cent of deaths and the average life expectancy would increase by a year if we followed international recommendations on each of these factors.

How can the Government help?

With better urban and transport planning. Barcelonians only do around 77 minutes of physical activity a week, when the recommended amount is 150. The air holds an average of 16.6 micrograms of particulate matter per cubic metre, when according to international guidelines it should be below 10 micrograms. We also suffer from very high noise levels: Barcelona exceeds the healthy limit, which WHO recommendations set at 55 decibels, by 10 decibels. When it comes to heat, the city centre can sometimes be eight degrees warmer than the temperature at the outskirts. And a third of inhabitants live far from a green space.

You have concluded in various studies that traffic pollution affects children in school. What legacy will we leave our children if we don’t take action?

The research group led by Jordi Sunyer, who is head of the child health programme at CREAL, has demonstrated that traffic pollution affects children’s cognitive development and their academic performance. Using a sample of more than 2,600 primary school pupils from 39 schools in Barcelona, and an average age of eight and a half, they analysed the effects of particulate matter (PM) in the air inside the schools. An increase of 4 micrograms per cubic metre of particles less than 2.5 microns in diameter – the ones that present the greatest risk to health – is associated with a 22 per cent reduction in working memory.

And no measures are being taken.

We have a political tradition that tends to ignore scientific evidence. In Catalonia, we’ve been working with the Catalan Regional Government’s Department of Health to incorporate the evidence into health planning, but the response is always very slow. In the case of schools, the appropriate measure would be to restrict traffic around them. In the Nordic countries there are regulations regarding the location of schools, based on air pollution.

Another important project at CREAL is the INMA programme on Childhood and the Environment, which involves groups of mothers and children that you’ve been following for more than ten years to see how they are affected by pollution.

Air pollution affects a baby’s birth weight, which is lower the more that mothers have been exposed to pollution during pregnancy. We found that for every additional 10 micrograms of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) or volatile compounds per cubic metre of air that the mother was exposed to, the baby’s weight was 91 grams lower. These studies are very important and the Government should take them into account.

Is it possible that PM can end up interfering in the way the whole body functions, in addition to the lungs?

These types of tiny particulates are the most worrying because they get right to the bottom of the lung and from there they get into the bloodstream, join the atheroma, cause chronic inflammation and spread around the entire organism. They can move from the olfactory bulb to the brain. We are certain that this is no exaggeration; in fact, quite the opposite: there are phenomena that are still little known and the problems may be even more serious. Only now are we starting to see the relationship with Alzheimer’s or diabetes.

They say that we are driving our cars less than we used to.

Levels of air pollution have fallen because we use our cars less, owing to the recession. But because there’s no money to buy new ones, the vehicles are getting older and cause more pollution. Up to now, nothing concrete has been done to reduce vehicle use: this is one of the most urgent measures that we have yet to take. We all need to walk more, cycle more and use more public transport.

Are superblocks a good public health policy?

They aim to decrease the total volume of traffic and, therefore, of polluting gases. They also provide another benefit: an increase in “walkability”. Physical exercise helps to reduce obesity and this has an even bigger impact on health. Excess weight and air pollution are directly related. For all the limitations of the superblocks project, it is a unique opportunity that Barcelona must not overlook. The days are numbered for the health of the planet if we do not work together to change the current model of development. Superblocks could make a major contribution.

At CREAL you’ve also been studying contamination from chemicals.

Diet is the main source of this. Fish contaminated by mercury has an impact on children’s neurocognitive development and has led to the establishment of dietary guidelines for pregnant women. We’ve also carried out studies on endocrine disruptors – dioxins – that are very persistent and poorly regulated.

All in all, it sometimes makes you wonder how we’re still alive?

Our organism has an incredible ability to adapt. We probably use more than 80,000 different chemicals, of which very few, perhaps one or two thousand, have been studied. The majority of them can be found in our bodies, albeit in tiny quantities, and we don’t know what effects they have… yet.

You are doing some uncomfortable research. Difficult studies on issues that some groups do not want clear conclusions from.

Yes, it is a disquieting science. Part of our research is often not to the liking of the big industrial corporations and they do everything they can to negate the studies or to undermine them. In Europe, this direct pressure is not as strong as it is in the United States, where it can happen that, if you publish an article that is very negative toward a particular industry, they sue you. They do it to scare off other researchers, to keep you busy defending yourself so you can’t work. A classic example is tobacco; the industry has used immoral strategies to try to hinder research and its application.

And the electromagnetic fields created by mobiles, how do they affect us?

At CREAL, studies by Elisabeth Cardis, Professor of Research in Radiation Epidemiology, has helped to get the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) to classify the use of mobile phones as potentially carcinogenic. To reach conclusions such as this one, a panel is formed with groups of experts that assess the scientific evidence and the industry also participates as an observer. The problem is that when the IARC publishes this, lots of media organisations and experts cast doubt on the evidence and claim that the results have no meaning. But they do.

So once again, we should be taking measures that we’re not taking.

The authorities in charge should take a serious look at the recommendations made in these studies. Many countries tend to just take preventive measures, like advising us to use our mobiles less, to use hands-free systems, to keep our devices away from vital organs…