Valdivia Statuettes

Dr. Ramiro Matos

Smithsonian Institution-National Museum of the American Indian

Valdivia culture

On the beaches of Guayas (Ecuador), in the early 1960s, small scattered hamlets of fishermen and potters were discovered, dating back to 3500 BC. Their discoverers, the Ecuadorian Victor Emilio Estrada and the North Americans Betty J. Meggers and Clifford Evans called them Valdivia culture, in reference to the geographic location where this culture was discovered and defined. It is the oldest potters’ hamlet known on the American continent.

In the Valdivia settlements, both on the surface and in the excavations, the dominant cultural material is high-quality ceramics, with varied form and decoration. It is not early pottery, but vessels made with refined technique. In the collections of fragments of ceramics, the statuettes modelled in clay stand out for their number, with a few in limestone. The vast majority are broken.

The statuettes carved in limestone pebbles have a form of rectangular laminas, with a vertical cut in the lower section to express the limbs, while the face and arms are drawn with simple line incisions. A few statuettes in stone that are known have the face and arms in relief and are more elegant. In the chronology of Valdivia, these lytic objects have been dated as the oldest, situated in the A Period (3500-2500 BC).

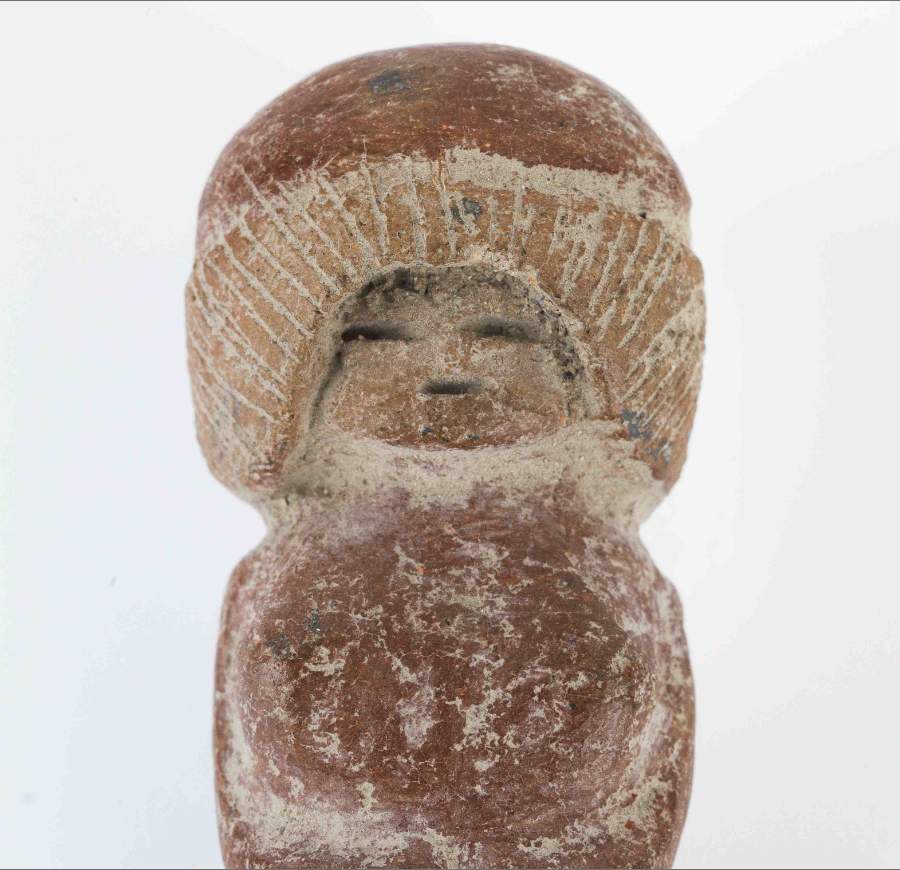

Statuettes modelled in clay

The statuettes modelled in clay, like those shown at the exhibition, correspond to the B and C periods (2500-1500 BC). These were the stages of the height of the Valdivia project, with massive pottery production, including the statuettes. Of note is the preference the Valdivia people had for representing female statuettes, highlighting their corporal attributes. The shape of the face varies between oval and square, with a lot of hair that falls over both sides of the face, generally combed or arranged with a parting in the middle. The size and representation of the arms are similarly varied, from small protuberances that project from the trunk to folded arms, some hanging and stuck to the side, others crossed with a straight angle on the elbow or making a curve below the breasts, depending on the age and status of the woman. The legs are generally straight and open, ending in a point. Seated statuettes are very rare, and are usually standing. All these images are covered in brick red englobe, and none are known to be painted. It is very clear that the craftsmen took great care in highlighting the beauty and attributes of the Valdivia woman.

Function and meaning

Regarding the function and meaning of the Valdivia statuettes, there are several interpretative hypotheses. One, based on the beauty and versatility of the statuettes, refers to the feminine qualities of the woman as an argument to consider them as a Venus, the “Venus of Valdivia”, the oldest of the New World, equivalent to Willendorf’s Venus in the Old World (Europe). This hypothesis is extended to motherhood and fertility of the woman, in a broader sense, to “mother earth”, to nature in general. The discovery of a tomb of a woman in Real Alto with a beheaded man as part of the offering leads to another argument for supposing that Valdivia society had been matriarchal and matrilineal.

On the other hand, the morphological analysis of the statuettes, differentiating and classifying the bodily characters, has enabled us to identify the different stages in the life cycle of women. It is obvious that Valdivia imagery shows with relative detail the external characters of the female body. Thus, the small statuettes that might represent puberty have a small and oval face, half the head shaven and with the use of a headdress, straight and flat trunk, short arms and legs, an absence of breasts and a subtle presence of sex. The statuettes of the following stage, identified as adolescence, show the head shaved in lines, small breasts, crossed arms, waist with silhouette and protuberant pubis. The adult woman, on the other hand, has thick hair, which is combed and/or arranged, square or oval face with a well-defined nose, eyes and mouth, large breasts, arms crossed below them, pubis with punctuations and the vagina. Finally, the pregnant woman has protruding breasts, large belly, arms crossed supporting the belly, and the head covered with a plain or embroidered biretta, showing little of the face. There are no known statuettes of women in the act of giving birth.

In view of the number of broken or fragmented statuettes, one hypothesis is that these had been made to be used as offerings, to be thrown into the sacred space in the context of rituals, during which many would obviously have been broken. Using comparative ethnography, some studies suggest the idea that they were a kind of amulet, similar to the Andean “illa” used as offering during propitiatory ceremonies, to fertility, the harvest and good luck. Some offerings were burnt, others buried or simply thrown onto the sacred ground. Perhaps the Valdivia statuettes were thrown onto the sacred space during the ritual, and in this case, some obviously broke.

To conclude, the hypotheses and suggestions outlined are not exclusive, and in fact we believe they may even be complementary. The Valdivia statuettes may have fulfilled several functions within the same society, depending on the ritual and the circumstance, and may even have been symbols of identity to differentiate one ethnic group from others. Future investigations will endeavour to clarify the controversy; meanwhile, we will continue to enjoy the beauty of the statuettes in the exhibition.

Related pieces

You may also be interested in...

Crosses of Ethiopia

Dr. Ewa Balicka-Witakowska, PhD

The small pendant crosses are worn by every Ethiopian Christian but especially by women, often as a complement to a cross-tattoo on the forehead, hand or neck.

Further informationThe figure of Krishna

The Folch collection has a fine selection of sculptures representing Hindu deities. We will focus on one of them, Krishna, to try and approach the complexity of these beliefs, which have the third-largest number of followers in the world.

Further informationNature in Japanese art

Dr. Ricard Bru

Both the ancient ethnic religion – Shinto – and the poetry anthologies dating from the 8th century show how the Japanese people’s profound empathy towards nature has become one of the main idiosyncratic traits of their culture.

Further information