Sandra Acosta: “Brain organoids represent an important leap forward in understanding the progression of Alzheimer’s”

An excellent communicator with extensive experience, Sandra Acosta details the extensive work being done at the Pasqual Maragall Foundation to understand in greater depth the mechanisms involved in the progression of Alzheimer's disease. As leader, since last April, of the newly created group (Research Group on Neurological Disease Models, one of the 6 available at the Barcelonaβeta Brain Research Center, BBRC), she focuses her work on organoids, small organs made from human stem cells. She has been researching with these biological devices for more than fifteen years, and this makes her an ideal reference and coordinator for this team that must help to understand in more detail how dementia progresses, and how it could be prevented, from which more than 100.000 women and men diagnosed in Catalonia currently suffer.

With a degree in biology (2004) and a doctorate in molecular and cellular biology from the University of Barcelona (2009), Sandra Acosta has traveled the world and has focused on neurodevelopment and studying the human brain in healthy conditions and in the face of diseases such as epilepsy or Alzheimer’s. She has been Serra Hunter Professor of Neuroanatomy since 2021 in Pathology and Experimental Therapeutics at the Faculty of Medicine of the UB, located on the Bellvitge Campus, and is a principal investigator in functional neurogenomics. She came into contact with Alzheimer’s about five years ago, following her conversations with Dr. Arcadi Navarro, director of the Pasqual Maragall Foundation since 2019, and is now beginning a new stage at the head of its reference center for research (the BBRC).

At the beginning of this year, a new group was created within the Barcelonaβeta Brain Research Center, which joins the 5 others already in existence: research into models of neurological diseases. Tell us how it came about and how it works.

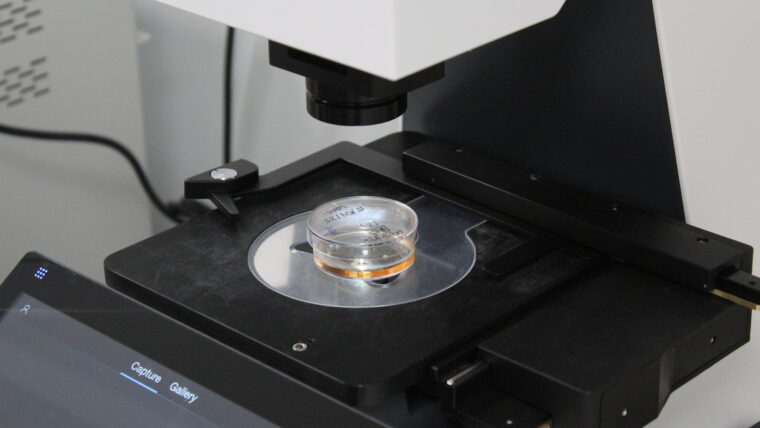

This is a new group that was created in April. A long selection process was opened months before, I applied and in the end they chose me, probably because of my experience in the field of organoids, where there are not many specialists. The team includes part of the group that already works within the UB and doctoral students, and contributes to the large network within the BBRC. We have 3 laboratories: the one at the university, the Barcelonaβeta Brain at the Foundation headquarters, and the one in the facilities of the Parc de Recerca Biomèdica, which incorporates advanced microscopes with much greater definition. We also have a small branch to study pediatric neurological diseases in Sant Joan de Déu. Our main tasks are to consolidate the monitoring of the evolution of Alzheimer’s and also of epilepsy, in phases of progression, not initial ones. We seek to understand those changes that occur at the molecular level with research and also with data from patients and volunteers.

All this within the framework of the brain organoid project that has been running for three years. How did it come about and what has been its evolution?

The work with mini-organs or organoids marks a major turning point for research. Its impetus comes from sources of funding and possibilities for expansion, which coincide with a progressive rise in these devices that are gradually being consolidated. They provide new, more precise data, which are added to the others obtained from experimental studies to form a more robust framework. Throughout this period, the five groups that existed before ours within the BBRC have been growing and, in some cases, incorporating organoids. But a more specialized team was missing, and that is why we are here.

For those who don’t know, tell us what an organoid is and how a brain organoid is created?

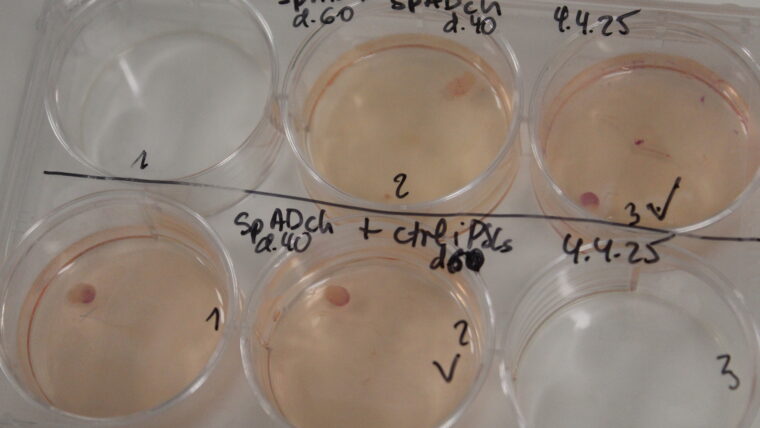

They are miniature organs, measuring a few millimeters thick. They are popularly called “mini-brains” but they are not as such because they are not attached to a body or have all its complexity. The creation process is very standardized. Stem cells are used (those that can differentiate into other cell types) that come from the large bank that the BBRC has of various human models (extracted from biopsies or from blood donors). These are reprogrammed, adding specific genes, to return them to their embryonic stage and transform them into induced pluripotent stem cells, which can then become any cell type. Some of them are frozen, to be available later, and others are transferred to cultures where they are administered nutrients, which are already very determined, and in a few months they generate mini-organs, in this case the brain.

About 30% may be defective, not well formed, or damaged during transport. That is why we are constantly creating more to ensure that there are always available for us and for our collaborators, such as the group that is investigating the effects of COVID at the Can Ruti Hospital. We currently have about 800 brain organoids available that are kept in very controlled conditions. They must be inside a stove, a container that is airtight and maintained at 37 degrees (the temperature of the human body) and continuously incorporates 5% carbon dioxide to maintain the acidity of the mixture.

In these structures you can observe different processes that should ultimately lead to facilitating new therapies and preventing Alzheimer’s disease. How do you work exactly?

We focus on understanding the progression of the disease as it progresses, beyond a purely initial phase. Many processes are examined and compared to draw certain conclusions. Above all, we observe biomarkers, certain molecular changes that are associated with this disease, such as amyloids (protein aggregates), or the Tau protein (very abundant in the central nervous system). And we look at RNA molecules (or ribonucleic acid, which transcribes the information provided by DNA) to define alterations and also genes that predispose to suffering the disease. On the other hand, we join two organoids, one healthy and one with Alzheimer’s and see if one transfers to the other, or we induce SARS-COV-2 in them to observe how this virus evolves in cases of dementia. At each step it is important to consider what happens to the synapses, the neural connections that, when broken, can damage extensive areas of the brain and produce toxic cascades, such as neuroinflammation.

Can brain organoids also be frozen?

Unlike many other organoids, which can be kept frozen to be available when needed, brain mini-organs are very sensitive, and therefore it is impossible to freeze them. It is a real shame, because it would save costs and some time in research, but it is totally impossible, today, not to damage the neurons and we have to manufacture them.

There has been an insistence lately on raising funding to continue this work. The “Minicervells per pensar en gran” campaign, whose donations will be used for the study focused on the development of miniature brains from stem cells to explore the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s, concluded in January and raised 312.820 euros. A success because it is more than you expected…

Rotund! Research requires a lot of money and if it weren’t for the many donors and these specific campaigns we wouldn’t be here. Just to create, so you can get an idea, these 800 organoids that we have, 6.000 euros are needed. And an advanced microscope like the one in the Parc de Recerca Biomèdica, with very high definition, about 500.000. If it weren’t for the help of people, all of this wouldn’t be possible.

Until recently, research into neurodegenerative diseases was based solely on animals (basically on primates or mice). What changes, apart from ethics and scientifically speaking, with this new in vitro method?

Well, we gain in precision and in many possibilities because we do not have to consider the regulatory and moral restrictions of working with a living being. First of all, a mouse cannot suffer from Alzheimer’s disease, and therefore the results obtained from it will not be extrapolable to what happens in people. The organoid, on the other hand, is human, and despite not being as complete as a brain, it is a relevant tool for research that opens up many new paths and provides us with much more complete detail.

Tests on mice help us understand how their neuronal system evolves in the event of any type of disease (infectious, degenerative, inflammatory, or even metabolic), and relate these records with the rest of the measurements. In the end we have a map where many pieces contribute (organoids, monitoring of volunteers, application in patients or data banks of people and animals) in order to relate them and draw conclusions.

You talk about changing research for therapies, and advancing a concept that is progressing: personalized medicine. How do you promote it and where are we in this field?

At the moment we differentiate organoids into certain groups, depending on whether they come from one person or another, because we all behave in a particular way when faced with affects. All this with evolution can lead us to create patterns of mini-organs, which will be much more faithful to certain people. And in a short time this can lead to investigating directly and much more precisely the evolution or certain remedies for individual patients.

Since 2013, the Barcelonaβeta Brain Research Center has been carrying out the Alfa Cognition project, which has been funded by the Barcelona City Council since 2017. Tell us what it consists of.

It is precisely one of the projects that adds basic data to better understand Alzheimer’s disease. Volunteers are offered, between 45 and 75 years of age, most of whom are descendants of patients who have suffered from Alzheimer’s. Through photo images and other tests, the evolution of neurons is followed (a fact that is very relevant because these are real brains). Genetic factors, the evolution of proteins, and other indicators are also monitored. All of this in the long term provides conclusions, such as, for example, that not all descendants genetically predisposed to contracting the disease end up developing it. And it links with the work carried out by other groups that identify the effectiveness of natural behaviors (good nutrition, physical exercise, or intellectual practice) to prevent the condition. These studies will continue over time until much more data and a longer and more robust series are obtained.

On the other hand, last December, the City Council signed an agreement to promote the Alzheimer Hub Barcelona. The Hospital de Sant Pau, the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, the Hospital del Mar and the Vall d’Hebron University Hospital will also participate. How do you assess this new initiative?

It is important for two reasons. To strengthen the entire field of research in the city (collaborate even more closely and expand the scope of everything that is investigated) and to attract funding. The city, in this way, presents itself as a leading hub, and makes it easier to attract both new talent and new money from the state or from Europe. And in addition, new grants are being opened to continue research, at the doctoral or postdoctoral levels.

In general, what do you consider to have been the most outstanding advances in this project and what is expected for the future? Will it be possible to prevent and have a cure for Alzheimer’s?

We have been able to make a lot of progress and have created innovative tools, such as brain organoids, but we are only in the early stages of fully understanding this major neurodegeneration. Other hypotheses are emerging and we have certain conclusions, but we need to make even more progress to understand all the processes and then, subsequently, investigate new remedies. Everything is moving very quickly and a lot of effort is being put into it. In a short time, it is expected that a lot of progress will be made, but for now it is impossible to say to what extent and even less to determine when it will be feasible to prevent or cure Alzheimer’s (in the important phases, those that already go far beyond simple initial lapses and entail serious consequences). However, it is clear that we are better than twenty years ago and there is hope and promising results.