Si els alcaldes governessin el món

Si els alcaldes governessin el món

[If Mayors Ruled the World]

Author: Benjamin R. Barber

Barcelona City Council and Arcàdia Editorial

Barcelona, 2015

527 pages

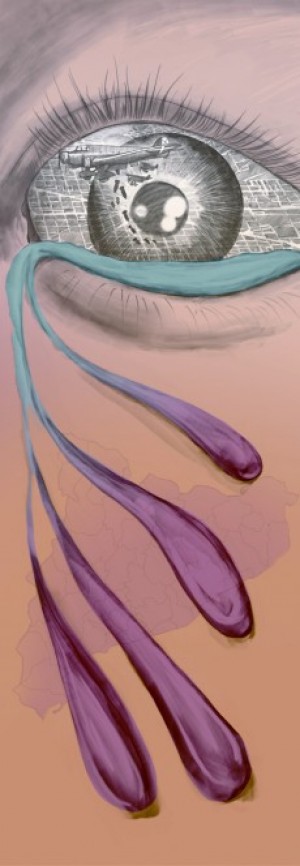

Globalisation has turned the old states into structures that are insufficient for developing democracy. Power is changing hands. The old metropolises can no longer compete via militarism, bureaucracy or mass production.

Every era has its progressive wave of thought, just as every era has its own forms of hypocrisy and leisure. It can be said that progressivism is the smooth and complacent discourse adopted by the powers that be, depending on the circumstances, in order to coax and nudge people along without making them feel imposed upon. Up until the fall of the Berlin Wall, the nation-state monopolised all areas of life and knowledge, and it was a core element in the discourses of the status quo. In Spain, where political cohesion is so fragile, the State continues to play an essential role in building progressive discourses, although in other parts of the world the social imagination changes faster. Globalisation has turned the old states into structures that are insufficient for developing democracy. With the advent of highly populated – and highly motivated – nations of the ilk of China, India and Indonesia, the old Western powers are looking for solutions to conserve their hegemony.

The latest book by Benjamin Barber, If Mayors Ruled the World, must be placed in this context. Power is changing hands. The West feels threatened precisely at a time when Western values are prevailing everywhere. The old metropolises can no longer compete via militarism, bureaucracy or mass production. As explained by Pankaj Mishra in From the Ruins of Empire, there are increasingly more reasons to believe that the former Asian colonies may eventually dominate the Western countries through the selfsame values that allowed the Europeans to conquer the world. To give one apparently harmless example: in 1991, selling 4,000 books gave an Indian writer best-seller status; now, the biggest-selling writers in India easily sell 55,000 books a week, and are read by millions of people.

The role of urban culture

In the face of the drastic scale of change faced by the West, cities emerge as an alternative that would allow the old democracies to continue playing an important role in the world. When all is said and done, urban culture is a creation of Europe and of the United States. Moreover, as Barber explains, in urban culture, sophistication, individualism and creativity are more important than violence and the power of the masses. Until only recently we were convinced that capitalism and material progress would unfailingly lead to a greater democratisation of the world. The growth of China and other Asian countries has brought this assumption into question. India itself, one of the West’s potential allies, is an unstable democracy, with extreme social differences and domestic threats.

Without this context it is impossible to explain Barber’s book and his proposal – quixotic or visionary – of creating a Global Parliament of Mayors, which would act as a counterweight to the UN and seek to promote a political culture more respectful of the management of empirical realities. Whereas in a world dominated by cities the West would be highly likely to maintain its hegemony, in a world of nation-states, democracy could be overcome by authoritarian-style capitalist models. When Barber describes the limitations that states impose upon the development of democracy, the economy and the world’s ecological sustainability, he is evidently talking from a Western standpoint – although he does not actually say so. For a Chinese, South Korean or Vietnamese person, the classic state still has a long way to go. The improvement in the quality of life the people in these countries are beginning to enjoy cannot be ignored.

It is therefore not strange that Barber’s book, and the proposal that underpins it, draws on studies that Western universities have undertaken on the phenomenon of cities and urban culture over the last decade. From a theoretical standpoint, the work is a compendium of already-published arguments about individualism, interdependence, cross-border spaces, pollution, women’s liberation, war and terrorism.

Barber follows in the footsteps of authors such as Richard Florida, Edward Glaeser, Saskia Sassen, Jane Jacobs and the Japanese writer Kenichi Ohmae, who had already written of the decadence of nation-states in the mid-1990s. From many different standpoints, all these authors had explained, before Barber, that cities are the most effective instrument for humanising the process of globalisation and for regenerating democracy.

The originality of Barber’s contribution lies in the fact that he takes this discourse to its logical conclusion, though the book’s very audacity is also what reveals its main defects. Perhaps due to his staunch defence of the need to create a Global Parliament of Mayors, the author bases his discourse on a sometimes over-naive faith in the city – such as when he says that terrorists hate the United States but have nothing against New York City. We have had enough that Barber makes a virtue of necessity. But we do not know –because the author does not say – to what extent he realises that a large part of the phenomena that he describes and the solutions he proposes are based on a highly simple fact, namely the debilitation of the power of the West and its need to fragment to avoid lapsing into rhetorical inanity.

A play to the gallery

Perhaps that is why the proposal smacks somewhat of avoiding the issue, a play to the gallery that is halfway between ingenious and childish. In this regard, it is significant that the prologue penned by Barber for the Catalan edition seems as if it could have been written by almost any spokesperson of the “third way” movement for Catalonia as a Federalist state – of the autonomous region status quo. Barber often seems to forget that cities do not promote wars only because states wage them (or have waged them) on their behalf. It is as if he failed to realise that one of the things which affords cities prestige is, in fact, that their power is limited, that they have scant capacity to impact the world dramatically and directly. The book’s logic echoes with the discourse we have heard so often in Catalonia about the population’s real problems and management understood as neutral action. It is true that city management enables politicians to better concentrate their efforts, but it is also undeniable that this capacity for concentration is taking refuge in increasingly smaller and empirical realities through the very decadence of the power that exercises it.