The book Vázquez Montalbán published in 1987 and which has now been republished in Spanish and translated into Catalan and English would be the ideal book because at the same time as you read it you can tour it as though it were a city.

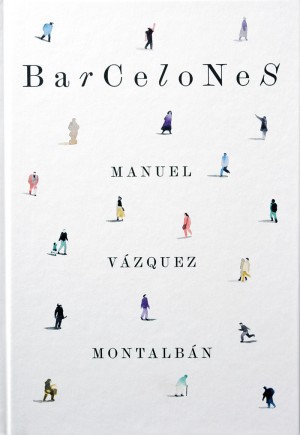

Barcelonas

Barcelonas

Author: Manuel Vázquez Montalbán

Published by: Ajuntament de Barcelona

358 pages

Barcelona, 2018

Every book, be it fiction, non-fiction or poetry, always has a centre of gravity. This is the question any reviewer is asked. I don’t know if this law (assuming it is one) is written down anywhere, but my years of experience in the business suggests it as an inescapable precept. One wonders what idea or ideas does the book I’m reading hinge on? No book doesn’t have its centre or centres of gravity. The same goes for cities. Which is why, when we visit a city we don’t know, the first thing we look for is the centre. A city can also be seen or ‘read’ like a book. And generally speaking, to find our bearings in a city hitherto unknown to us, we take along a guide –a book, in short.

In a way, Barcelonas, the book Vázquez Montalbán published in 1987 and which has now been republished in Spanish and translated into Catalan and English would be the ideal book because at the same time as you read it you can tour it as though it were a city. I am almost certain the author was not unaware of this symbiosis between book and city, this tour on which the reader does not only turn pages, she also tours streets, neighbourhoods, squares, monuments and people. And feels, just as you intuitively feel when you walk around our city, the layers making it up, its various archaeologies, its adjacent surfaces.

I use the word archaeologies in the same sense Manuel Vázquez Montalbán uses it in his book, and the phrase ‘superficial archaeological prospection’ comes to my mind. This type of archaeology refers to a type of research which, instead of at the bottom of what is being studied (excavations), takes place on the surface, as though it were being observed from an aeroplane, so that the results obtained by that new way of looking at a complex area, a landscape (rather more than just a stage) are richer and unexpected.

Well, the first thing one finds with Barcelonas is that it is not the typical book that talks about a city along historical lines. So it is not a history book but a book of memory, which is something very different. Barcelonas is not driven by landmark events. It’s a deconstruction of Barcelona, which is what you would expect, bearing in mind the eminently deconstructivist intelligence with which Vázquez Montalbán always analysed reality. Or rather, realities. There is no way of analysing any human landscape with any guarantee, either moral or sociological, unless we record the contradictions making it up. This is exactly what deconstructing is. And that is how the intelligence of the author of El pianista works.

Barcelonas is driven by concepts and perspectives. Each one is a chapter, a way of organising it that has no bearing on a historical unfolding, though it is a historicist one. Let’s enumerate those concepts, which in turn become perspectives and vice versa: ‘From the hills’, ‘The submerged cities’, ‘The free man in the free city’, ‘La Ben plantada’, ‘The occupied city’ and ‘Millennium’. When you read it, the book does not hide a sort of synchronic structure, although at the end what dominates are the diachronies and superstructures the whole text rests on. Barcelona is a cross between thickness and surface. The former is in the latter, excavating is not enough, you need to overfly the ground as well. Rise above its ceilings. It’s a law that is probably called for in any study of a city. We must not overlook the author’s Marxist training either. That’s why I spoke above of deconstruction –that is, the method by which one can surprise the contradictions all reality contains.

More solemnly, I would also say that Barcelonas is a treatise not just on Barcelona but on how to write about a city with a long history like ours. Are there other ways of telling this story? Of course. If, for example, we read the no less canonical Barcelona, by Robert Hughes, we will find a philosophy that is closely related to its author’s usual practice and a way of committing oneself to the city he knew and fell in love with, but without ever losing sight of his trade as an art critic in the interpretation of ‘his’ Barcelona.

Rereading Barcelonas today can still mean reading it with the same admiration with which we read it the first time. That prose, seemingly programmed to restore in the memory of the people of Barcelona the intra-history pasted to the walls of their city, the historical slanders, the humiliation handed out to its inhabitants, alternating with brief days of boundless joy and hope. I’m sure the author read Italo Calvino’s Las ciudades invisibles. And he must have asked what category his dear Barcelona could fit in to, following Calvino’s classification: ‘a subtle city or one according to its skies, its desires, its names, its memory, its dead or its eyes? Readers now have the floor.