A series of new projects have begun to come to the fore in recent years in the world of arts and artistic education. These projects tap into classroom experience, but they are more flexible and responsive to the social reality they seek to improve, leveraging the power of music as a factor of cultural and human development. They are led by figures with non-traditional profiles who combine creativity and activism.

Author Archives: Eva Vila

Rediscovering the power of music

True musical action does not talk about the number of music schools, of results in terms of numbers or sales, but rather the transforming power of music and the richness of art as a catalyst for social needs.

© Fabiola Llanos

Musicians of the Sant Andreu Jazz Band, an ensemble founded seven years ago at the Sant Andreu Municipal School of Music.

The teaching of art, and music in particular, has been revisited in recent years from different standpoints. Not just by the authorities and teachers, but also by artists, social educators and students themselves. First of all, the content of programmes in compulsory and higher education has had to be revised to bring music up to speed with other subjects and, as a result, Barcelona now has three schools that offer a higher diploma in music: the Escola Superior de Música de Catalunya (ESMUC), the Liceu and the Taller de Músics. Secondly, the number of music schools and the range of extracurricular activities have grown. All this has helped to complete a process for the standardisation of courses which has allowed us to start extricating ourselves from an anomalous situation, namely that art has long since been on the fringes of our society.

However, true musical action does not talk about the number of music schools, of results in terms of numbers or sales, but rather the transforming power of music and the richness of art as a catalyst for social needs. This is why new ideas in the world of art and artistic education have come to the fore: long-term projects that seek a solvent way out of a spiritual and value crisis; proposals that innovate and open up new paths; paths that are not plotted around the tables of an office, but in the street, in contact with the children, and become reliable indicators of transformations taking place in society while they are also transformed by it.

In the current debate, different voices agree that there is one thing that cannot be staved off any longer, namely that we cannot abandon culture if we do not wish to lose the values that contribute to personal growth and the development of our society’s identity. While in other fields, such as health, taking measures to prevent and alleviate costs and the future effects of the population’s bad habits is common, similar tools that would allow us to take care of the soul of tomorrow’s society are still regarded as utopian. With the shortage of resources, the truly essential becomes patent: the priorities of the community and people. Educating through art is an opportunity for the society of the future because it will enable us to develop significant findings, such as flexibility and integration, that will be much needed by children to build the society that is taking shape.

For some time now, new methods lying outside established frameworks have been proposing changes geared towards affording greater scope for creativity. Classroom experience is generating new proposals that are more flexible and open to social change in order to respond continuously to the needs of the community, thus making artistic education and culture a true social yardstick once and for all.

New professional figures are also emerging in the wake of these changes. A new profile has been born, somewhere between creator and activist, combining the facets of artist, teacher, social worker and manager; someone capable of engaging and liaising with decision-makers in many different areas, responsible for spearheading renewed musical and artistic activity. These professionals collaborate together and with other networks – organisations, neighbourhoods, schools – but above all they are committed to children, young people and their families. Open dedication, as yet not fully defined, is a long way ahead. Some examples of this are analysed in the following pages.

The irresistible magnetism of the Sant Andreu Jazz Band

The SAJB project is driven by a work ethos that leads its members, children and young people aged between seven and twenty, to play out of need, out of the desire to feel good and convey this to others.

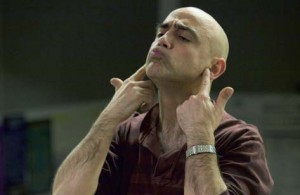

The group during a rehearsal, conducted by the band leader, Joan Chamorro, a tutor at the Musicians’ Workshop.

Today there is no way into the municipal school of music of the Eixample district, as a throng of people of all ages are blocking the entrance. It is hosting a concert by the Sant Andreu Jazz Band, currently the most glamorous children’s and young people’s orchestra, conducted by the jazzman Joan Chamorro. A band with three albums, a documentary and international impact that attracts musicians from all over the world to Barcelona to collaborate in the project.

In the band’s ranks, boys and girls between seven and twenty years old perform a repertoire of jazz, above all swing, from the thirties and forties, with catchy melodies and a rhythm rooted in dance. Where does the SAJB’s magnetism lie? It could be summarised in a single gesture, that of Elsa Armengou, a seven-year-old girl, as she gives the tempo to a twenty-strong orchestra before taking up her own trumpet to play; this, as well as the joy, rhythm and naturalness with which they perform their music from the stage. You can feel that the project is underpinned by a work ethos that leads them to play out of need, the desire to feel good and to communicate this to other people – family, friends and the audience.

How utterly vital these experiences are in our fragile ecosystem! In 2011, the Sant Andreu Jazz Band gave a knockout performance at the Palau de la Música. The SAJB undoubtedly has the hook of being a group where the stars of the show are boys and girls, with the charisma of a voice like Andrea Motis’ to boot. However, if you drop into a rehearsal you will also be charmed by the voice of Magalí Datzira, by Alba Armengou on trumpet and Eva Fernández on saxophone. Besides brimming with good musicians, the SAJB’s great virtue lies in taking classic and popular jazz to audiences who hitherto had never been attracted by this type of music. Glenn Miller, Louis Armstrong and Sarah Vaughan have become part of many people’s soundtrack just as easily as the children take to the stage as another part of their learning process.

The Sant Andreu Jazz Band was founded seven years ago in the municipal music school of Sant Andreu as just another instrumental group, with no intention whatsoever of becoming what it is now. The result is the product of the methodological work of one of their teachers, Joan Chamorro, known for his thirty-year career as a musician, especially as a baritone saxophonist in various bands, and twenty-five years as a teacher. This background allowed him to cultivate an educational experience that is now yielding fruit. Five years on, the SAJB project has surpassed the expectations of the Sant Andreu school, so much so that it is now proving difficult to contain. It is by no means easy for the school to manage a group of students who may start to generate income through the sale of albums and concerts, hence the decision was made to take it outside the school. In 2011, the Sant Andreu Jazz Band became an independent and self-financed project based at the Taller de Música school in the municipal facilities of Can Fabra.

We have to grow

Chamorro fully realises that the goal is not to make money, although this does not mean that the SAJB should exist merely as a school group. “I want the project to grow so that people can see what kind of music children aged nine and twelve years old are capable of making and get other kids to fall in love with it.” The need to explain what is going on in the SAJB is just as compelling as the need the children have to feel that their concerts and music are “real”. As real as the names they refer to constantly during rehearsals or concerts: Billie Holiday, Sidney Bechet, and so on. Is it pretentious for them to attempt to imitate a sound that has captivated them in order to captivate others? This is the traditional method for the transmission of flamenco, or the same one that the son of Alfonso Carrascosa, the latest SAJB member, has grown up with, just like many children of musicians who started to play through imitation, watching and listening to their parents and the friends of their parents who frequented their home.

Instead of mechanically repeating studies and scales, the SAJB children listen repeatedly to the great jazz compositions. Following them and imitating them is their first wish. This is followed by the excitement of being part of a group of friends and musicians, and finally, concerts, sharing stage with such prestigious guests as Jesse Davis, Terell Stafford and Wycliffe Gordon, who became their stage-mates during the concert at the Palau de la Música. If music knows no boundaries, why not let the students cross them beyond the school walls?

Chamorros’ theory is that most of what is learnt in music should come from listening. When a child starts out, they should go straight to the music, the sound, not how it is coded through language, because as yet we do not know if the person will need to use it. Music should come before writing. “It is not a new methodology, but many people are wary of it because, depending on how you look at it, it may be regarded as anti-dogmatic and anti-conservatoire. There are still many things that appear to be immovable. It is taken for granted that children should be grouped by ages or begin to learn through reading and writing music. However, by doing this we are telling the child that they should wait to have a perfect technique to be able to make music or take to the stage. It is believed that most children, particularly smaller ones, cannot climb onto a stage and give a good performance.” Chamorro began to think about recording discs and DVDs to show people what was going on. The first one was with some great friends and musicians from Catalonia such as Ricard Gili, Dani Alonso and Josep Traver, who wanted to participate in the spirit of the SAJB and turn it into a celebration.

Teaching how to love music

“We often hear conversations about how ‘most children do not study’ and teachers would rather work with older students because at “least we can demand more of them”. “This”, explains Chamorro, “is a mistake we have made. Of course there must be willpower and rigour, but what does ‘demand’ mean? The teacher should know how to motivate or encourage children, and before teaching them music, he or she should teach them to love music. You need to make music appeal to children; they should see it as fun. A child will never be motivated to study if we tell them that they will be able to play within a year as long as they study hard. My students start with a song they learn by ear and will be able to play within a week. A note in itself is not important to a child; what they listen to is the melody in their head.”

Tired of years of studying that did not offer students the certainty of being able to play with the same ease as they read a book, Chamorro thought that there was something wrong with the way music was being taught. A teacher of musical language at the Taller de Músics, he developed a colour system to explain tonalities, relationships between notes and other elements of harmony in order to facilitate, among other things, improvisation.

“When you use the actual music without considering the coding of the language, and you do so from your own feelings, you are creating a true connection with the instrument. The results with groups of children aged seven, for example, are amazing. They do not play anything that they do not listen to or sing internally. This is their language. As they study out of pleasure and enthusiasm, they retain things better. And you should hear them improvising! A lot of musicians would have loved to improvise the way these kids do! Only this deep connection with the instrument will make creative musicians of them, a musician who not only reads but also has the ability to sing, to put their fingers in the right place and know what it will sound like.”

So far, eight former members of the SAJB are working in music here or abroad, but regardless of whether they eventually become professional musicians, Chamorro knows that this will have touched their lives forever.

The Voices project, or the Venezuelan seed

In 2004, in the district of Gràcia, sixteen children started up the project Voces y Música para la Integración (Voices and Music for Integration), an initiative with which the conductor Pablo Gonzalez revived, in Barcelona, the theory and practice of music of the famous National System of Youth and Children’s Orchestras of Venezuela.

The Voces project, headed by Venezuelan musician Pablo González, is based on work with the voice, and in a secondary phase, collective instrumental practice. One of its social aims is to integrate the children of families from elsewhere into local life.

When the Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra was not yet what it is today, i.e. a symbol of social integration through the values of music, Jose Antonio Abreu was already planting the seeds of a great project in his students. Almost from out of nowhere, from the grass-roots, from the provinces, without any resources, without any precedent, he instilled an ambitious dream among the first young people that worked with him – the dream of building an orchestral centre for children and young people in every city in the country, next to the church and the town hall: places which Abreu calls núcleos (cores) and which form the basis of the National System of Youth and Children’s Orchestras of Venezuela, known worldwide as El Sistema (the System).

Since its inception, Maestro Abreu’s sensitivity has been focused on conveying to his students the importance of music as a socialising phenomenon. Therefore, each one of them, besides playing, has always had the option of forming a new orchestra, of dedicating their time to creating a grassroots awareness of music in underprivileged places scourged by poverty and marginalisation, and taking music to them as a social rescue tool. They say that Abreu once had a seventeen-year-old who had done time for bank robbery and major crimes brought before him. “I am going to give you the chance to change your life; I’m going to give you a clarinet,” he said. “I want you to study in El Sistema.” “And aren’t you afraid I’ll steal the clarinet?” asked the kid. “You won’t steal it, because it’s yours.”

The same desire for inclusion was what led the Venezuelan musician Pablo Gonzalez to start the Voices and Music for Integration project in Barcelona. It was in 2004, in Gràcia, under the auspices of the Sant Felip Neri Oratory. This was how sixteen children became the founders of what is now the seed of the Venezuelan System implemented in Barcelona. The initial idea was to include children from other countries. At that time, the wave of immigration was huge, and serious problems were beginning to arise inside and outside schools. Why not design a programme like the youth orchestras in Venezuela, but with the aim of uniting children and families from abroad with others from here? Nine years on, lack of integration is still due, more than ever, to economic reasons; the status of many families has changed and children have to adapt. “What better way of facing up to the new situation by singing, playing and having fun?” Pablo tells us that he used to watch many of the children who are now in the orchestra playing football in the local square, until one day they stopped him and told him they wanted to study flute, violin or bass. “After that we meet the family, the parents, and go to knock on doors if need be. Far from the idea of creating a ghetto with specific characteristics, here we have children from all over the place. When we play we are all equal. There are children of doctors who could afford a music school but would rather be with us.”

Six years with the Simón Bolívar Orchestra

Pablo González had the privilege of sharing six years of rehearsals with José Antonio Abreu in the Simón Bolívar Orchestra. “When he explained musical phrasing to us it used to come with a complete philosophy. For Abreu, any musical note can transmit. What you need to know is what that phrase means, and put all your feelings into it to express it, otherwise you might be able to play but will never communicate. The Czech composer Antonin Dvorak, for example, when invited to conduct the New York Conservatory, was the first composer to allow black musicians into a conservatoire, at a time when it was thought that black people could not play the violin for biological reasons! Only this kind of stance, driven by a certain radicalism, could beget a work such as the New World Symphony. While the children are here making music we also try to remind them what is happening on the other side.”

Captivated by the instrument, Pablo entered the núcleo in his city, Maracay, at the tender age of twelve. “When I started out they gave me a cello and put me into the orchestra. Just two months later we had a meeting with Maestro Abreu in the Caracas Polyhedron Arena. Imagine, twenty kids from the provinces in a stadium full of people to play with an orchestra of 500 musicians. ‘We are not needed here’ I thought! But we were all important for the Maestro and the system. We played Beethoven’s Fifth.”

Basically, the only thing the Voices project pursues is to create youth orchestras that sound better and better and let the kids have fun. Work is based initially on singing and then performing with the instrument collectively. The first time they come in, the kids walk out singing with their classmates. So they are given the chance to participate immediately, to be in the concerts and see society in a different light.

Pablo Gonzalez got involved the local grassroots of the Venezuelan youth orchestra set-up when he was aged just twelve. In the picture he practises the cello with one of his students in Barcelona.

Musical points of reference

It was at one of these concerts in Les Basses Civic Centre where the District Councillor fell in love with the project and offered the centre to the cause. The project also has sites at Roquetes (where other initiatives have been running for some time now, such as the Roquetes Nou Barris Symphonic Band), Ciutat Meridiana (where there are virtually no music schools), and Sant Andreu. The idea is to grow and turn these places into points of reference for children, where they can form their own groups (chamber orchestras, choirs, etc.) and feel that they are part of the project with new initiatives (hip hop, musical theatre, etc.)

It was during Barcelona’s Mercè festival in 2011 that Ana’s seven-year-old twin daughters, Barbara and Fabiola, on the violin and cello respectively, got their chance. “When we saw them we were stunned.” It was a Sunday lunchtime. It was raining. The whole choir was on the stage that had been set up in the middle of Plaça de Catalunya. They got in contact immediately and started out with awareness-raising and singing. Two months later they had chosen an instrument and joined the A orchestra. Today we are watching them rehearsing with the B orchestra. Everyone is preparing for the concert they will give in the Auditorium of Barcelona on 10 May with the Barcelona Symphony and Catalonia National Orchestra (OBC), together with the kids from Xamfrà, another educational project that has been using music as a tool for social transformation in the Raval district since 2005.

Besides the OBC, more and more musicians are collaborating with these projects. Two years ago, Natalia Smirnoff, violinist with the Vallès Symphony Orchestra, contacted Les Basses as a volunteer. Little did she think that she would meet Pablo there, whom she had played with for four years at Simón Bolívar. “I greeted him and confessed that I felt as if I was in one of the núcleos.” They are one of the first generations of musicians produced by El Sistema. Later it produced such famous names as the young conductor Gustavo Dudamel, aged thirty-two, director of the Simón Bolívar since 1999 and one of the standard bearers of El Sistema, a framework that has created several products (music groups) to export Venezuela’s national identity and culture. Its success proves that when a country understands what its wealth is, it can export it with results that surpass expectations.

We might say that belonging to the Simón Bolívar Orchestra is the highest goal within Venezuela’s Sistema, and only the best make it. Being at the top of the pyramid means being a role model for 350,000 children and more than 180 núcleos all over the country. While you need to be really good to get in, there is no minimum age limit. Natali knows children who joined at the ages of twelve and thirteen. Those who don’t make it give classes in the núcleos or form new ones, because youth orchestras are constantly developing.

“What really matters”, he explains, “is that when you listen to a núcleo from a neighbourhood in one of Venezuela’s provinces and then you listen to the Simón Bolívar, you know for sure that one day the orchestra will sound just like it. Because it isn’t just about music; it is also about ideology.” People have tried to export the model across the world. France is one of the few countries where it has failed to gel because the priority there is to focus on finding the best students from the conservatoires in order to produce orchestras that sound good. The essence is lost. “Many people we have met, who are now soloists and conductors of the best orchestras in the world, would not be where they are today had it not been for music. That is why one day we would like to have a great youth orchestra in Barcelona, a professional orchestra born of our own system.”

The new education of Barris en Solfa and Do d’Acords

The Argentine musician Pablo Pérsico, who has been living and working in Barcelona since 2007, is the driving force behind a new educational system, Integrasons, which has created two children’s and youth orchestras in Badalona and Poble-sec.

© Arxiu Integrasons / Marta Pich / SGAE

The Do d’Acords Orchestra during the concert they gave in June last year, in partnership with the OBC string quartet, at the Artèria auditorium on Avinguda Paral·lel.

In all orchestras there comes a moment when the soloist goes out on a limb. What would happen if they sounded off? The whole group, the whole piece, would be jeopardised. This moment, recorded in a musical score and performed at a given moment in our present, sums up the educational project created by the Argentine composer Pablo Pérsico. A new methodology based on the possibility that one day we will have to give our all with a whole orchestra behind us and an audience in front of us. When I first heard the Barris en Solfa orchestra I was reminded of Mireia Farrés, solo trumpeter with the OBC, playing the opening notes to Mahler’s Fifth Symphony with a full orchestra behind her almost in silence. How do you launch a boat that will later have to switch to cruising speed?

Barris en Solfa, conducted by Pablo Pérsico himself, comprises of fifteen children from different backgrounds, each of whom has between five to six different instruments. They are all unique and fascinating instruments – a didgeridoo, guaguatub, xylophone, Chinese harp, bongo, maracas, etc. Today we are watching the orchestra rehearse. Each child follows Pablo Pérsico’s instructions depending on what they are listening to at the time and chooses an instrument. The maracas are just as important as the xylophone. Or vice versa. The idea is to choose the most appropriate sound based on what the rest of their friends are doing. The methodology encourages the children to make mistakes, which should not be feared but rather integrated into the experience.

Collective improvisation is something that is far removed from official school programmes, but in Barris en Solfa it is part of the children’s initial learning. Each one of them is invited to conduct the orchestra and get it to improvise on the basis of very simple parameters. They all want to play, they all want to conduct, they all want more. They are hungry for music. They are children from different schools, put forward by the neighbourhood’s social organisations. Every Tuesday and Thursday they meet at the Consorci Badalona Sud to work with Pablo Pérsico and his collaborators, some music teachers and other volunteers who started out knowing nothing about music and have learnt at the same time as the children.

Today is concert day and there is a feeling of complicity between the volunteers who play alongside the children and Pablo, who reminds us that what we are hearing is the fruit of months of work without playing a single note. These children, with different family circumstances, came to this place two years ago to become carefree children. Music was not even the top priority. “We started out by building instruments and playing about with sounds, because while we build all are equal. If you fail to build together, if your partner does not play with you or does not play well, that affects you. And it is not a question of philosophy or interpretation – our hearing does not lie! It is so obvious when you are out of step! So music requires teamwork. We have to work together so that each child is in sync with the rest, because problems are shared. By giving the children in the group responsibility we change the focus of education.”

The Integrasons methodology

The project proposes a new methodology of musical initiation underpinned by four core values – listening, attention, respect and community. The methodology known as Integrasons is based on “tasting” sound and timbre. I had never heard kids talk so naturally about the timbre, dynamics and structure of a piece. Pablo thinks it is important to explain to children that the sound they are making must be listened to from beginning to end, that attention must be paid to how it is executed, because that will impact everyone else and everyone should therefore work as a team. In musical learning, timbre is usually one of the most overlooked elements, the last lesson in the book that we never reach. Pablo explains how working with timbre and sound opens up a new dimension, a new gateway into music that is not melody or musical language but rather sound as a vibration. It allows us to gauge music as an ensemble of vibrations. “What are we if not sound? Vibration! As of now we all vibrate together. I have always been about playing with vibrations,” he says, “about tapping into children’s capacity to be surprised and fascinated by sound and using it to develop a new methodology.”

This is why for years now Pérsico has been dedicated heart and soul to looking for and selecting instruments from all over the world, collaborating with instrument makers who participate generously.

Great sounds in Poble-sec

The Integrasons methodology is also the driving force behind the children’s and youth orchestra Do d’Acords, which for the last four years has underpinned an educational, artistic, cultural and social project in Poble-sec.

In 2007, Pablo Pérsico arrived in Barcelona to do a Master’s in Management and began to take part in different orchestras, going into the classrooms of primary and secondary schools to work with teachers and learn about how things are done in Catalonia. Pablo had been working in music schools in Argentina for ten years, particularly in schools for the children of politicians. Being familiar with different realities is probably what has allowed him to imagine a new methodology, which he has been testing on heterogeneous groups of children everywhere. The results are constantly evolving, but they clearly show that the integration of values can be learnt and developed through sound, producing excellent results in children’s development and their capacity to build the future.

Argentinean composer Pablo Pérsico heads an educational project based on a new methodology to introduce students to music in Badalona and Poble-sec.

The Do d’Acords orchestra has managed to engage the inhabitants of an entire neighbourhood, regardless of race or economic status, as well as institutions, groups and, what is most important, dozens of young musicians who hope that the musician who came to their school one day and pulled some amazing instruments out of his trolley will maybe offer them the chance to feel unique and part of something. “Poble-sec deserves a children’s orchestra to represent the neighbourhood,” says Pablo. “I believe that Poble-sec has the chance to generate a high-quality orchestra of international renown, not so due to their technical capacity with a cello or trumpet, but because they will be unique when performing here and in Europe thanks to their creativity, relationships with the instruments and relationships with each other. It will be an example of how music can be created and transmitted.”

Last June, the Artèria Paral·lel hall rung with applause for the concert by Do d’Acords with the OBC string quartet, didgeridoo and tabla musicians and an instrument maker who designed a fascinating instrument for the occasion. “The power of applause is enormous in that it fuels the children’s self-esteem,” says Pablo. “The project makes sense through this recognition, which allows the children to understand many things. Growth is three-dimensional because they are doing something they had never expected they would. For a few moments, they are the centre of attention, they are heard by others in an ideal setting and are rewarded with sincere and grateful applause. When children hear this, they enter a process of transformation. They have discovered a habit, something that disquiets and stimulates them, a curiosity, a foundation that will help them to get by in this society we live in. Art as a vehicle of transformation.”

In the near future, Pablo Pérsico is addressing the challenge of how to improve instrumental training in terms of working with timbre and sound, according to his initial methodology. While it is true that Integrasons breaks away from traditional instrumental teaching, it greatly enhances learning in later phases because there are well-understood and well-established values in place. “Musical education as we have conceived it leads to missed opportunities that go beyond merely playing a score. In the long term, the value afforded by studying an instrument is unmatched. The child who actually learns to play an instrument and communicate with music attains an inexhaustible wealth. If the child consolidates their relationship with music they will have established a leitmotif that will guide them through life. What matters most is that children are creators. I do not train performers, I train creators. And I think that this is what Europe needs most right now: to train positive leaders.”