Globalisation has led to more mobility and cultural exchange around the world. More than 300 languages are spoken in Catalonia, including Abo’o, Armenian, Beti, Hawaiian, Inuit and Welsh. The city of Barcelona is home to a large number of the immigrants who come to the region and has become a mosaic of very diverse cultures and languages.

According to the municipal census, there are currently 347,897 people of foreign origin in Barcelona, many of whom are not familiar with the Catalan reality when they arrive here. They think that Spanish is the language spoken here and it is usually the first language they learn. In some cases they decide to study Catalan later as it makes life in the city easier. In other cases they do so simply to regularise their status, because they need to have proof of a minimum knowledge of Catalan to get a certificat d’arrelament [certificate confirming being established within the locality that makes it possible to get work permits and residency].

However, newcomers have difficulty finding a place to practise Catalan and usually encounter Spanish in social situations, especially in big cities like Barcelona, since the local people are used to using Spanish with newcomers. Even though foreigners might start a conversation in Catalan, the majority of locals respond in Spanish, which can lead to certain frustration and to them giving up learning Catalan.

Here, we present a sample of different groups to see how they have adapted to a multilingual city like Barcelona.

The British: looking for quality of life

The Mediterranean climate and quality of life – life outside the house, the food, social relationships – are the main reasons why Brits decide to live in Barcelona: they account for 2.44% of the foreign population. British people usually live quite spread out around Barcelona’s neighbourhoods, but there are concentrations in the districts of de L’Eixample, Ciutat Vella, Sant Martí and Gràcia.

Although the majority of British people who live in Barcelona usually have English-language-related jobs, language is not an obstacle to integrating and, in fact, they usually intermingle with the local population and often form mixed couples. According to data from the Statistical Institute of Catalonia’s 2011 population and housing census, 72.1% of British people understand Catalan.

Brazilians – an open community

Brazilians are, in general, an open community who are able to integrate very easily. They usually live spread throughout the city rather than being grouped into closed communities. This community is fairly large and diverse in Barcelona, in a similar way to their country of origin: 2.1% of the foreign population is from Brazil. These data are not completely in line with the reality, however, because there are people with dual nationality.

Thanks to the fact that like Spanish and Catalan, Portuguese is a Romance language, it is easier for Brazilians to learn them than for other groups. “People who have received an education have probably studied a bit of Spanish if they’re thinking about living in Barcelona, but not Catalan,” explains Andréia Moroni, a PhD student in sociolinguistics and President of the Associação de Pais de Brasileirinhos na Catalunha. People who are not educated usually only speak Spanish, although there are also those who “don’t end up speaking either of the languages and stay at an intermediate point, which isn’t Catalan or Spanish, but it’s not a problem for them to live here,” says Moroni.

Italian pragmatism

Italians account of 9.16% of the immigrant population in Barcelona, although these data are not totally reliable, because some have dual nationality. They usually live in different districts such as Ciutat Vella, L’Eixample, Gràcia, Sants-Montjuïc o Sarrià-Sant Gervasi, rather than in closed communities.

In general, Italians tend to use Spanish in interpersonal relationships and leisure contexts. According to Nicola Vaiarello, visiting investigator at the University Centre of Sociolinguistics and Communication (CUSC-UB), the author of a doctorate on Italians in multilingual educational contexts. behind this attitude lies a discourse of usability: “The relationship that Italians experience with Catalan, as a regional language, is influenced by their language of origin,” since Italy is made up of regional languages and dialects that do not have an official status. “If they had an official status, that would translate into more prestige for their own languages and, in a multilingual context, into a positive attitude towards the situation of Catalan bilingualism,” he observes.

Reserved Pakistanis

Pakistani immigrants – who account for 7.42% of the newly-arrived population – usually settle here for economic and work-related reasons. The majority are young, Muslim (although there are minority Christian communities) and speak Punjabi, a majority language in Pakistan, although it is not official: Urdu is the official language and language of prestige and is what is taught in schools.

Since this group’s priority is finding work, the issue of language is secondary and the interest in taking Catalan courses is focused on obtaining the certificat d’arrelament. There is also a third factor in addition to the first two: “If you don’t love your own language, it is difficult to understand the status of Catalan, because you see Spanish as the language of prestige,” notes Imanol Larrea, a PhD student who has studied the case of Pakistanis in Barcelona. However, there are people who see Catalan as a way to integrate: this is the case of the Pakistani Workers’ Association, a finalist for this year’s Martí Gasull award, which is given by the private organization Plataforma per la Llengua to a person or organisation that works to defend the Catalan language.

Berber sensitivity

The majority of the Berber population, from North Africa, especially Morocco and Algeria – 4.78% an 0.64% of the immigrant population in Barcelona, respectively – is concentrated in towns in the Barcelona Metropolitan Area, such as Cornellà de Llobregat, Sant Joan Despí and Sabadell, and in the Barcelona neighbourhood of Torre Baró.

Although this is a group that largely conserves their customs – particularly in terms of interpersonal relationships, traditions and religion (they practise a popular form of Islam, mixed with local customs) – they have an open mentality, take part in social life and show a sensitivity towards the linguistic issue because of the situation of their own language in their countries of origin.

People with a low level of education or no education who have come here for work reasons usually limit themselves to just learning Spanish, while those who have attended university have more sensitivity to Catalan, as noted by Äl·la N Ayt Lhu (Abdellah Ihmadi) and Aziz Baha, Secretary and President of the Casa Amaziga of Catalonia, respectively.

The Japanese – a monolingual group

The Japanese form a small, little-known population in Barcelona: they account for 0.58% of the foreign population and live in districts such as Sarrià-Sant Gervasi and Les Corts. Their degree of integration varies depending on their migration plans.

On the one hand, there are those who are just passing through, workers invited by Japanese companies or teachers at the Japanese college, who only stay temporarily and are focused on maintaining the customs of their country. They do not usually sign up for Catalan courses and prioritise Spanish, something that reflects Japan’s monolingual ideology.

On the other hand, there are those who settle here for family, cultural or academic reasons, who adapt to local customs, combining them with their own. They sign up for Catalan classes “out of curiosity”, but they do not use it as a customary language: “The second generation of Japanese immigrants or mixed couples, however, usually use Catalan as their customary language,” says Makiko Fukuda, Professor of Translation and Interpreting at the Autonomous University of Barcelona and an expert in language transmission in mixed families.

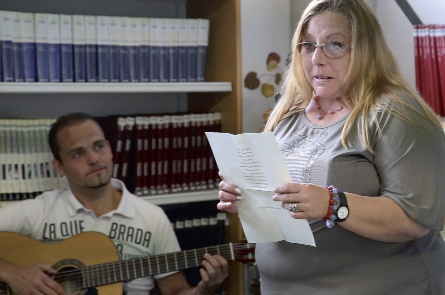

(Note: In the photos at the beginning of the article, from left to right, Javed Ilyas, founder and president of the Pakistani Workers’ Association; Andréia Moroni, president of the Associação de Pais de Brasileirinhos na Catalunha. The italian investigator Nicola Vaiarello, the japanese professor Makiko Fukuda and, together in the last photo, Aziz Baha y Äl·la N Ayt Lhu, president and secretary of de la Casa Amaziga of Catalonia.)