The Panikkar Year inaugurated on February 5th commemorates the hundredth anniversary of the birth of the philosopher, and has a double objective: to promote his work and debate on the validity of his thoughts on understanding the current world.

Panikkar is a philosopher with an intense, complex and eventful biography that tells us about his work, explaining it and making it possible. We can get a first glimpse at this biography by looking at his name: Raimon Panikkar i Alemany. The fact is, that wasn’t always what he was called. Panikkar changed the spelling of his name as his ideas evolved. Let’s start at the end: Alemany. It’s the family name of his mother, Carme Alemany, a daughter of the Barcelona bourgeoisie.

Well-educated and refined, Carme Alemany was interested in philosophy and often interacted with the cultural circles of the noucentista movement. In 1916 she married Ramuni Pániker, an Indian who had left his first wife with child in India, coming to Europe to seek his fortune. And find his fortune he did: his chemical products business (“what Pániker sticks stays stuck!”) reached considerable size and became decisive for the economic welfare of his entire family. When Ramuni Pániker reached Europe, that’s how he decided to transcribe his name: Pániker. That’s the name he would pass on to his four children, and that’s the spelling that would always be used by writer and philosopher Salvador Pániker, Raimon’s brother. However, when Raimon travelled to India, he discovered that his paternal family name could more accurately be transcribed Panikkar, and from then on that’s how he wrote it. By doing so, he sought to show his deep respect for his Indian heritage.

Then there’s “Raimon”. When Panikkar was born, his first name was recorded at the Civil Registry in its Spanish form: Raimundo. That’s the name he used to sign his first books, published by Editorial Rialp, associated with Opus Dei. Later, he would come to spell it “Raimon” in all his books. In 1997 he went to the Civil Registry to officially change his name from “Raimundo Pániker Alemany” to “Raimon Panikkar Alemany”.

In summary, by going from Raimundo Pániker to Raimon Panikkar, he was Catalanizing his first name and Indianizing his last, and both steps are quite significant. Panikkar always identified as a thinker with a Catalan and Indian background. His intercultural proposal, summarized in his interreligious mantra “I left a Christian, found myself to be Hindu and became a Buddhist, all without ever ceasing to be a Christian”, is inspired by this double background. It’s as if he was genetically destined to embrace multiple cultures and religions.

Panikkar always insisted that his work had been experienced. In the prologue of his book Mysticism and fullness of life, he claims that he was tempted to tear up the manuscript so that the subject would take root in his life. In the “Editorial by the author” of his complete works, he solemnly declares “none of the writings I have the honour and the responsibility of presenting were born from simple speculation. Rather, they are all really autobiographical, meaning they are inspired by life and praxis, and it was only later that they were put into writing.” What can be said about the life and the praxis that inspired the work by Raimon Panikkar? We know a good deal about it thanks to the controversial biography written by Maciej Bielawski (Fragmenta, 2014).

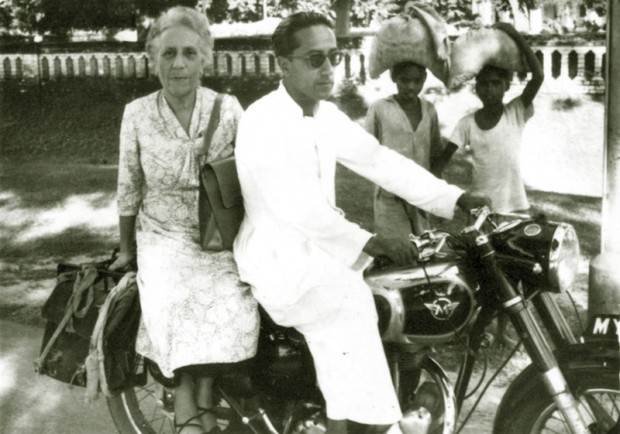

Panikkar was born in Barcelona in 1918 on the corner of Carrer Rector Ubach and Carrer Santaló. He studied at the Jesuit school in Sarrià. With the outbreak of the Civil War, he and his mother were persecuted for their dedication to Catholicism. He took refuge in Germany, where he studied chemistry. After the war, he returned to Barcelona by bicycle. In 1939 he met Escrivà de Balaguer, and the following year he joined Opus Dei. He studied science, philosophy and theology. In 1946 he obtained his doctorate in philosophy and was ordained as a priest. He lived first in Madrid, then in Salamanca and finally in Rome; these movements had to do with conflicts within Opus Dei. In 1954, with the death of his father, Panikkar decided to honour his memory by travelling to India for the first time. He initially stayed there for four years. In 1958, he obtained his doctorate in science in Madrid, and in 1961 he got his doctorate in theology in Rome, giving him a total of three doctorate degrees: in science, philosophy and theology. Years later, Panikkar would write abundantly on what he called cosmotheandric intuition, according to which reality consists of three interdependent realities: nature (kosmos), man (anthropos, Andros) and God (Theos). Xavier Melloni has noted that Panikkar’s three doctorates correspond with these three dimensions: his science degree involves the study of the kosmos, his philosophy degree explores the anthropos and the theology degree has to do with the Theos. Life and thought are connected once again.

In 1966 Panikkar came into conflict with Opus Dei, which expelled him after a canonical process we are gradually coming to understand more and more. He then moved to India and was incardinated as a priest in Varanasi. From 1967-1972, he taught at Harvard University. In 1972, he became a professor of compared philosophy of religions at the University of California, Santa Barbara. During his tenure at UCSB, he divided his time between India and the United States.

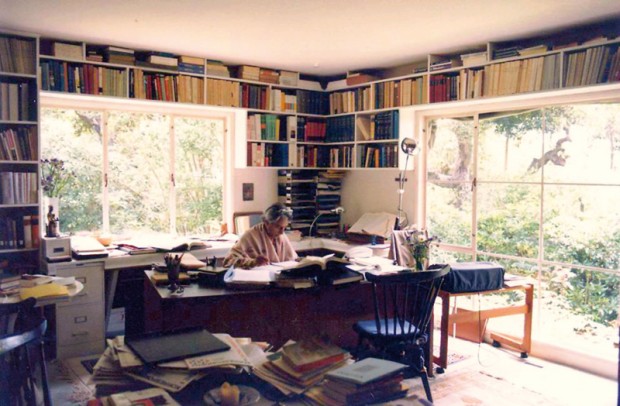

Panikkar at home in his study in Santa Barbara, California, where he was a professor in compared philosophy of religions starting in 1972.

Photo: Fragmenta Editorial

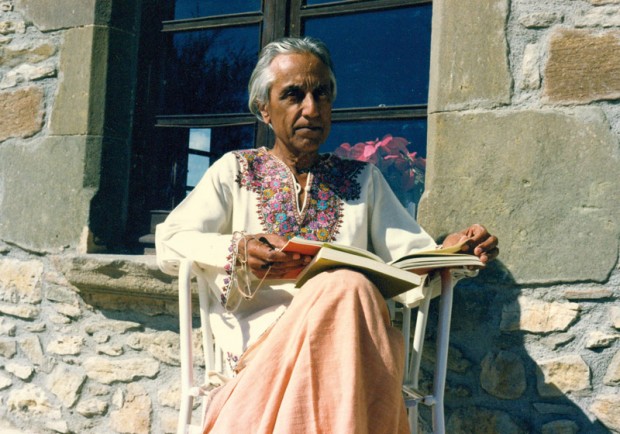

In the mid-eighties, Panikkar retired and took up residence in Tavertet, where he created Vivarium, Centre of Intercultural Studies (today the Vivarium Raimon Panikkar Foundation). The final years of his life were spent mostly in this town in the foothills of the Catalan Pyrenees. His home became a place of pilgrimage for disciples and friends, eager to hear the words of the man they considered a master. However, Panikkar never ceased to travel the world, giving conferences and participating in all manner of academic events.

In 2008 Panikkar began to publish his complete works, the result of seventy years of intense dedication to writing: “I haven’t lived to write, but I have written to live in a more conscious manner and to help my brothers with thoughts that have sprung not really from my mind, but rather from a higher source we might call Spirit.” In fact, for seventy years Panikkar continued to produce without interruption: some sixty books, hundreds of articles, innumerable public talks, no end of participations in the media… Panikkar didn’t flee contact with the public, and was eager for his intellectual and spiritual ideas to help to forge a different world, more respectful of diverse cultures and traditions and more critical of the techno-scientific empire.

Interreligious dialogue

In 2004 Panikkar participated very actively in the Parliament of World Religions, the most successful and impactful opportunity for dialogue of the many that took place at the Universal Forum of Cultures in Barcelona. Panikkar dedicated a great deal of effort to promoting interreligious dialogue, on which he theorized a great deal.

In 2009, Barcelona awarded him the Gold Medal of Cultural Merit. The same year, he publicly presented his complete writings at the CaixaForum in Barcelona. This was to be his last great public event. He died in Tavertet in 2010. The following year, the city paid him homage in the Saló de Cent of the City Hall. And at the start of this year, on February 5, the Saló de Cent was once again the venue for the inauguration of the Raimon Panikkar Year, dedicated to the philosopher. Promoted by the Government of Catalonia, the Barcelona City Council and civil society, the Panikkar Year commemorates the hundredth anniversary of his birth with a double objective: promoting his work and debating on the validity of his thoughts on understanding the current world.