A mouse is a peripheral. Anyone who has set up a computer knows this. Mice and peripheral areas, neighbourhood policies. A periphery that no longer seems to exist and yet has never stopped existing. A periphery more about urbanites than urbanists. The districts have been transformed, but there is still no justice.

Being from a peripheral neighbourhood is like being in Burgos but without local products. The neighbourhood is itself a product of the land, of cement, where your shoes don’t wear down so much. These are all things which once proclaimed ring hollow. Yet they are still applicable, because they have never ceased to exist, because it was said by elderly neighbours as they readied themselves to defend against the day-to-day penalty shoot: there will always be poor people. That is an utterance not only of resignation but of a will to survive (not to perpetuate oneself: that’s for the rich). Barcelona’s radios and its outlying areas are filled with aerials pointing to Tibidabo Mountain, the tallest thing that can be seen from far away. The aerials pointed towards the Expiatory Church of Tibidabo look like fishing rods angling for radio stations.

The word extrarradio (outskirts) was invented when somebody noticed a strange throng of people with radio sets listening to the football matches of FC Barcelona, Real Madrid and the Spanish national team; programmes where it was possible to dedicate songs, send congratulations… the radio hosts Elena Francis and Montserrat Fortuny, because wherever there’s a Zorro there’s also a Coyote. Foxes, coyotes, stray dogs, mice. A mouse is a peripheral. Anyone who has set up a computer knows this. Mice and peripheral areas, neighbourhood policies. A periphery that no longer seems to exist and yet has never stopped existing. A periphery more about urbanites than urbanists.

The forest

The periphery, the outskirts, that idiotic way of naming a grouping of districts, which expands as a living, rhizomatous thing from Sant Cosme and Bellvitge to Singuerlín, Pomar, Les Guixeres, etc., by way of Sants, Ciutat Vella, La Pau, etc. It is a type of roving existence with its own economic, population and landscape transformations and all manner of changes except those that are geographical in nature. But the fact that the land remains can be explained by geo-politics, and before it was said by Ecclesiastes. The way in which the districts have changed is being studied more frequently and more in depth.

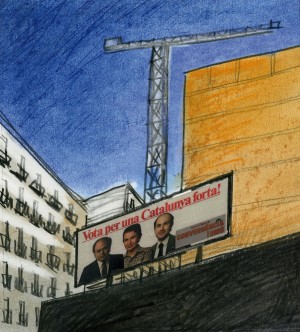

For example, journalist Marc Andreu has just published Les ciutats invisibles. Viatge a la Catalunya metropolitana (The Invisible Cities. A Journey to Metropolitan Catalonia; L’Avenç, 2016), which shows what the media have not dared to say, and have not even been able to see. But the periphery is precisely that, a class bias. Marc Andreu’s book discusses, amongst many other subjects, people in the districts who don’t watch channel TV3 except when a Barça game is on. Who do not in the least identify with the image of Catalonia that people in power have endeavoured to project. The book also delves into the worlds of Chinese residents who buy bars from retiring migrants, the Pakistani-owned grocery stores and the pisos patera (overcrowded immigrant flats) in Badalona’s La Salut district, amongst other topics. It particularly speaks of the habitat made up of neighbourhoods that the people call “city”. Neighbourhoods that seem invisible from the outside, like when a dense forest does not let you properly see its trees.

Trees

Barcelona has perhaps the saddest trees in Europe, if we do not take those around the Chernobyl nuclear plant into account. I am not referring to the trees themselves. Once stuck in their holes, the poor things do as best they can. I am rather talking about the way they are made to exist. Trees in Barcelona seem like a hindrance, or worse: they have been put where they are so as not to be a hindrance. This is what has happened, in general. Urban planning in the districts, something akin a manicure given to a poor person, has resulted in trees being pulled up where they were growing in leafy abundance only to be rearranged like a set of streetlamps. Now the trees seem not to have much personality, like rows of unisex trees, to borrow the neighbourhood hairdresser’s terminology.

The branches of the weeping willows with their resin tears, the befuddled fig tree in the middle of a vacant lot. Freedom, the individuality of being a tree. Barcelona does not like trees. The city pulls them up because it does not know what they are good for. It is not even a matter of class, but of the whims of power of a certain class.

It happened in Sant Gervasi (spoilt upper-class, although well-educated pijos). The jujube tree on a plot in Carrier Arimon, which the late writer and translator Isabel Núñez defended, even as she defended her own life to the end. It once occurred to me to say how funny the bourgeoisie sounded when defending their plots of land. She was not at all happy about it, but she forgave me and that is why I say it here, because that tree from an upper class district is now the wonderful emblem of all the free trees in each and every Barcelona district. The city with no other attribute but democracy, the city as a human chain, the city as a rhizome.

Sant Gervasi is also a peripheral district when seen from the apartment blocks in Sant Roc de Badalona. Not the more recently built ones, but the ones that are still languishing down in Carrer Alfons XII: with the concrete of the facades all rotten and dirty and the names of young people painted on them, dirty pavements, open rubbish bins, neighbours sitting in their chairs and whiling away the time with bird cages on their cars or hanging on the walls. This is the heart of a community (to use the terms of the conciliatory Christianity of Pope John XXIII, who has a street named after him in Badalona), this is the nerve centre for many people, some of whom never find it in themselves to spend any time outside the district, and hence everything around them is the outskirts, the periphery, the outlying areas. Hell is the others, and the outlying areas are the air that separates us from them.

The muck

The boulevards, promenades and avenues of London, Paris, Berlin, New York (to name four very European cities). Given the sumptuousness and generous width of streets in big cities, individual districts are left with flaunting the width of their pavements. Looking towards a better quality of life and higher levels of welfare, the pavements have been getting wider around groups of homes in places where there were hardly any pavements thirty years ago. The transformation of such places has made it possible for people to comfortably walk to the dole office.

Photo: Dani Codina.

The metropolitan coastline of the north side seen from the Colomense Singuerlín neighborhood.

The other night groups of volunteers combed the streets of Barcelona and other cities within its metropolitan area to make a count of poor people sleeping on pavements, in cash machine enclosures, etc. In Badalona, which has more than two hundred thousand inhabitants, they counted thirty-nine. Less than forty – the years of a certain dictatorship.

The gleaming pavements of the districts extend outwards like the leisure marina quays that coastal town councils have been busy building. But with the crisis came more muggings than moorings. And we are once again seeing syringes under bridges, in street rubbish bins, under the trees planted in the flat pavement cement. Safety fences around the train tracks that have been torn up by scrap sellers. The industrial estate has gone belly up and become an estate of commercial warehouses run by Chinese citizens. Homeless people from all over the world sleep under the shelter of a hypermarket structure. Piles of rubble lie beside the tracks, opposite La Plataforma de la Construcción, the building material warehouse where the unemployed wait bright and early for a van that will give them a ride to work (enabling employers to transport material and labour in one go). All this shows that the districts have indeed been transformed, but justice has not been done.