The private bridges are the oldest in Barcelona, but there are also among them a couple of modern and well-known ones: the false Gothic bridge in Carrer del Bisbe, and the “bridge of shame” in Carrer de les Egipcíaques. But there is no bridge dedicated to the devil.

Barcelona does not have a river, but, my goodness, it has a lot of bridges. Pont de Marina, Pont de Mülhberg and Pont de la Foixarda are just some which exist today. Pont de la Riera d’Horta, Pont dels Àngels and Pont de l’Esparver, to name three that were around in the 20th century. And there are yet more: in Sant Martí there is an area called El Barri del Pont, bridge district, and Nova Icària Park is known as the park of bridges.

A bridge is a construction erected over a depression or an obstacle, like a river, valley or train line, which allows passage from one side to the other. A bridge makes you happy. It is always beneficial. Think about the Game of the Goose, and ponts in the calendar, those extra days off between public holidays and weekends. On top of this, a bridge always has a little bit of magic and wonder about it. We journey from here to there without getting muddy, going up or down or sweating, just straight ahead and there we are. A bridge unites things that are separated, and a car thief hot wiring a car bridges the circuit to start the engine. No wonder that some bridges are supposedly fingers of the devil, because all bridges remake nature; some people even claim that they alter divine creation. Pont del Diable, the Devil’s Bridge, just legends, but Satan’s appearance is something that remains in the spoken word and the world of bridges. There is a phrase salvar un riu, save a river, where salvar means to avoid an obstacle or overcome a difficulty; even so, the first meaning of save is to protect from death: salvation; or in other words, to remove yourself from evil, from the Devil.

In Barcelona there are no devil’s bridges, and these days there are not many that overcome geography. The majority are railway bridges, and, particularly ring roads, fast lanes and motorways. Those in Barcelona are bridges of the industrial revolution; bridges of modernity. It was not always like this. When there were no trains or cars, geography was much more in evidence. You could see that Barcelona is on an inclined plane, boxed in between the Collserola range and the sea and hemmed in by two rivers. This, as well as the series of hills (Rovira, Peira, Creueta, Carmel, Putxet and Monterols), mean that in some places the slope is quite pronounced. To “save” this topography there is the Vallcarca viaduct, and the neighbouring Plaça Mons bridge, which span two branches of the Vallcarca creek; and the Reina Elisenda bridge over J.V. Foix and the Duquessa d’Orleans, where the Sarrià stream bed passes. Watercourses that have disappeared because they have been buried or channelled into the sewer system. And what was once water is now the land of cars and people.

Most bridges communicate and solve problems of physical geography, and have a particular orientation. Parallel to the Collserola and the hills, to allow passage between the waters that descended to the sea. The railway bridges have a different orientation. They are other way round, perpendicular. The train lines crossing Barcelona were problematic and dangerous. More than just the noise and smoke was the trench, a new and terrible frontier imposed by industrialisation. It separated streets and neighbourhoods, living spaces that until then were next to each other. The solution was to build some bridges. Although, really, only a few. On Carrer d’Alcolea and Carrer del Nord (today Galileu), in Sants. Pont del Mico, in Aragó/Casanova. And on the east side, the bridges of Marina, Espronceda, Treball and Maquinista. A handful of bridges and some level crossings, always cheaper than building an overpass. And we know that cheap things often end up being expensive. If only in terms of human life.

The bridges go over water torrents, expanses of rails, even the sea, like the Porta d’Europa, a bascule bridge connecting the Ponent and Adossat quays, and, sometimes, also “saving” streets. These are private overpasses. Like all bridges, they make life easier; in this case, only for individuals as they are not public.

Between home and paradise

Of all Barcelona’s bridges, these include the oldest in the city. Carrer Carabassa has two. They joined houses on one side to gardens on the other. They appear to be 18th century. The one on Carrer dels Ocells must have had the same function. That on Mercè and the one on Sant Pere are in very claustrophobic neighbourhoods. Narrow streets and small plots. Anyone who could, bought the space opposite to make an allotment or a garden. On one side a dwelling and on the other a little slice of heaven, a corner of paradise.

There is another special iron and glass bridge on Passatge Bacardí. Whilst the Carabassa and Ocells bridges are open, that on Bacardí is not. This is one of the things that makes it unique: a covered bridge in a covered space, as is this passageway. The other is that the glass had been painted with tropical landscapes. The bridge still exists, but there is not a trace of the decoration left.

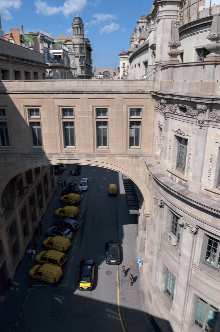

The most common private bridges are those that run between the different parts of institutional buildings. The Carrer del Bisbe bridge, joining the Palau de la Generalitat with the Cases dels Canonges, is perhaps the best known example. It is by Joan Rubió Bellver and was inaugurated in 1928, in those delirious years when, demolishing something here, moving buildings there, the Barri Gòtic was invented. Because of its pretentiousness, a Gothic overload, no one liked the bridge, and it was the butt of many jokes. Ricard Opisso created a series of four drawings, where in each one he pointed out the ridiculousness of the construction. It is now one of the most photographed sites in Barcelona. If the Generalitat had a bridge, City Hall could not be left out, and they, too, have their own. It is more discrete and tucked away. It runs from Carrer de la Font de Sant Miquel, and links the old building with that in Plaça de Sant Miquel.

© AFB

The Santa Maria bridge, which linked the Basilica of Santa Maria and the Palau Reial, which partially stood until the nineteen eighties, in an image from the start of the twentieth century.

The Santa Maria bridge

Private bridges isolate folk; they pass over the street, over other people. They are the symbol of a way of life. Such is the case of the nobility. In Pla de Palau, in front of the Llotja, there was a Gothic building, remodelled over and over again, property of the city, which in 1654 King Philip IV made his own. The king decided that it would be home to his viceroys. In the Bourbon era, and up until 1844, it was the residence of the captain-generals and from that time on it became the royal palace, housing the monarchs when they happened to visit the Catalan capital, right up until Christmas 1875 when it was entirely destroyed by fire. Or almost entirely: the bridge was saved.

The viceroy, Prince of Darmstadt, had had it built in 1700. It was covered and left from the palace, ran down Carrer de Malcuinat, continued along Fossar de les Moreres, Carrer de Santa Maria, and reached the temple at the height of a spacious gallery on the Epistle side. The bridge was demolished in 1823 by resolution of the City Council and rebuilt again in 1827. It lasted quite a few years and can still be seen in photos from the 1980s, as well as in private collections. It was one of the first paintings of Santiago Rusiñol: Façana lateral de Santa Maria del Mar, des del passeig del Born (1887).

In fact, the Santa Maria bridge was not a unique construction; instead, it followed tradition. In the cathedral there was a bridge linking the Royal Palace with The See. Its remains can be seen on the facade in Plaça de Sant Iu. This bridge is from the time of the fat and devout King Martin the Humane. As it was difficult for him to get about, the chapter agreed to this construction as a work of piety and to save the monarch from the breathlessness and fatigue of the steps. The bridge was demolished “in our days”, wrote Pi i Arimon in 1854.

Bridges in the Generalitat, City Hall, the Church, more bridges in the State’s administrative buildings. Behind the main post office is another special bridge, put up at the same time as the building (1926–1927). Not far from there, in Carrer d’Ocata, is yet another. It is lower and shorter, and joins the two station buildings a way to remind us that many of Barcelona’s bridges are there to “save” the railway lines.

In Carrer de les Egipcíaques there is another unusual bridge with sad memories. It goes from the regional seat of the Spanish National Research Council (known as the CSIC) to the Institut d’Estudis Catalans: a bridge that reminds us of Franco’s occupation. Thanks to a decree signed in Burgos in 1938, the Instituto de España was founded, which one year later became the CSIC. Like all institutions created in times of conflict, it took away everything it could: the work, premises and property of the Junta para Ampliación de Estudios, and, in Catalonia, the Institut d’Estudis Catalans. In 1942 it reached Barcelona. It was housed in flats until 1952–1954, when it built itself a colossal building, and, in the middle, was a bridge: an advance to occupy enemy territory. A bridge of shame that still exists.

There are further bridges; they are happy and fun. And in Barcelona there are almost as many as there are parks. Recently it has been typical to put bridges in newly designed parks. They are only decorative and serve to show just how deeply the art of building nativity scenes is rooted in this country.