Barcelona has seen periods of interreligious coexistence as well as appalling episodes such as pogroms, Inquisition tribunals and the burning of convents. Today, the city is a point of reference for peace between religions, which provide cohesion and coexistence. How has this been achieved and who made it possible?

Open session and prayers at the centre of the Naqshbandi Haqqani Sufi order, coinciding with Barcelona’s Nit de les Religions [Night of Religions] on 17 September 2016, an initiative by the Young People’s Interreligious Group, part of the UNESCO Association for Interreligious Dialogue.

Photo: Vicente Zambrano

Although the history of religious diversity in Barcelona goes back a century and a half, it is perceived as a novelty because it now has so much public visibility, and it was only included on the political agenda 20 years ago.

We can say that religious diversity has grown exponentially in recent decades, counting believers or centres of worship, with the understanding that many religious practices have spread extraordinarily through participants without religious affiliation: meditation, yoga, tai chi, gospel music… However, beyond the numeric growth, this pluralism has become more diverse as well, up to the point that it is difficult to distinguish the religious and spiritual initiatives from many others that are philosophical, parapsychological, humanist and philanthropic in nature and, even – let’s face it – for profit.

From repression to freedom

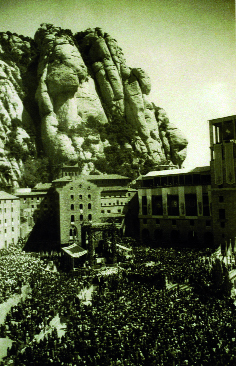

A crowd gathers outside Montserrat monastery, drawn by the celebrations for the enthroning of the Virgin of Montserrat, in 1947. The events, promoted by the more open sections of the Catholic Church, were the first meaningful attempt at reconciliation with people opposed to Franco.

Photo: Pérez de Rozas / AFB

The darkest hour for religious freedom in contemporary history was the Spanish Civil War. Opponents of religious freedom (both supporters of National Catholicism as well as the anti-clerical factions) launched a vicious attack on democratic Catholics and believers from other faiths. The first significant gesture of reconciliation did not arrive until 1947, with the festivities celebrating the enthronement of the Virgin of Monserrat, actively promoted by the more open Catalan Catholics, clearly opposed to the dictatorial regime.

These same sectors created structures and dynamics along the lines of the later Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), in favour of freedom, pacifism and ecumenicism. That period saw events in Barcelona such as La Caputxinada, a student sit-in at a Capuchin convent, the subsequent protest by priests and the founding of Workers’ Commissions (CCOO) in a parish, while entities were created such as Pax Christi, the International Catholic Movement for Intellectual and Cultural Affairs and Justícia i Pau (Justice and Peace), which often work with other social entities. The Ecumenical Centre of Catalonia was also founded, which, under Fr. Joan Botam, became the benchmark for ecumenicism.

The process of secularisation made this pro-reconciliation movement lose some of its fervour, but eventually its principals of dialogue and open arms ended up becoming the usual pattern for cooperation between religious communities, some of which had been decimated during the dictatorship and others introduced with great precariousness.

Turning point

The consolidation of religious freedom in democracy, the immigration of peoples from countries that were not very or not at all secularised and the cultural exchange facilitated by globalisation phased out the old disputes over the role of religion in society and, in particular, the mistrust between faiths.

In five years there was a blossoming of interreligious dialogue in Barcelona and social recognition of the religious reality, turning the city into an international point of reference. The city council created the Barcelona Inter-religion Centre, now the Office of Religious Affairs (OAR), in 1999, and one year later the Catalan Government started up an agency that is now called the Department of Religious Affairs. Both institutions commissioned a religious map from a team at the Autonomous University of Barcelona led by Joan Estruch, which brought out all the religious diversity hitherto unknown. Its circulation promoted a more plural image of the city, while policies of institutional recognition, subsidies, awareness raising and mediation began.

In parallel, under the expertise of Raimon Panikkar, the leadership of Fèlix Martí and the management of Francesc Torradefolot, the UNESCO Association for Interreligious Dialogue was created, which has been the most fruitful laboratory for this dialogue: it creates dialogue groups, publishes the magazine Dialogal and other materials, advises government agencies and coordinates the Catalan Network of Interreligious Dialogue Entities, which brings together around 20 associations stretching from Perpignan down to Alicante, and from Lleida across to Palma de Mallorca. Together with the city council, the Association successfully brought the Fourth Parliament of the World’s Religions to Barcelona, in the framework of the 2004 Universal Forum of Cultures. Consequently, the Archbishop of Barcelona created the Standing Working Group on Religions, which brings together five of the city’s communities. With this platform, the synergy between institutions, academia and society is rounded off with coordination from representatives from the Catholic, Protestant, Orthodox, Islamic and Jewish faiths.

This avalanche of projects has not been free from tensions, but it has established a basis of trust, mutual understanding and horizons that consolidate coexistence in the long term. Although it does not serve any pre-established plan, it has ended up building a unique system. It has become a benchmark at international level, not so much to be copied, but rather as a sustainable model that grows (agencies such as the Advisory Council for Religious Diversity, publishers such as Fragmenta, etc.), while it is also reproduced at local level. Thus, for example, when it was announced that an Islamic prayer room would be relocated to El Raval, a group of entities from different faiths came out to defend the right to open a centre of worship. In Barcelona, all faiths cooperate in favour of the freedom of worship.

This interreligious cooperation will be put to the test constantly. The international context is becoming tense again, thanks to jihadist extremism and Islamophobia. At national level, now that religious freedom is not a questioned right, cooperation between religions and state will need to be addressed. The necessary updating of obsolete regulations on religious freedom will force the prerogatives of the Catholic Church to be eliminated (areligious option) or extended to other faiths (pluri-religious option). In any case, the understanding of the city’s religious partnerships and networks of diverse actors prevent the proliferation of prejudices, limit the scope of possible conflicts and put the dialogue preached by all faiths into practice.