As an architect and town-planner, Puig i Cadafalch left a profound and lasting mark on Barcelona. But as a politician, despite the importance of his role as successor to Prat de la Riba at the head of the Mancomunitat of Catalonia, his work has been questioned.

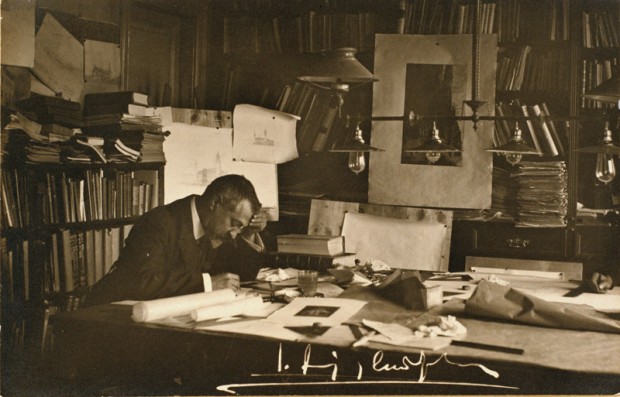

A complex, many-sided man, Josep Puig i Cadafalch (1867-1956) was also a remarkably cultured man – an architect, town-planner, archaeologist and restorer of Romanesque art – and, secondly, a politician. Even so, his work in this field has made him an enormously uncomfortable figure. Through ignorance or out of ideological interest, history, which is always much more complex than what is left in writing of it, has been very demanding of him and has not given him the place he deserved.

The early death of Enric Prat de la Riba brought Puig i Cadafalch to the Presidency of the Mancomunitat (1917-1923), the first national institution since the defeat of 1714. In this way, he became the continuer and executer of the work of his predecessor. Before that he had been one of the founders of the Catalan right-wing political party Lliga Regionalista, a member of Barcelona City Council (1901-1906), a deputy in Madrid (1907-1913) elected for the Catalanist coalition Solidaritat Catalana, formed in response to the attacks on the magazine Cu-cut!, as well as a deputy to Barcelona Corporation (1913-1914), the germ of the subsequent Mancomunitat of Catalonia.

For his immense architectural work alone, Josep Puig i Cadafalch deserves a place of honour in the cultural history of Catalonia. Barcelona today still bears testimony to his commitment and his activity in this sphere. He was one of the three most outstanding architects of Catalan Modernisme, along with Domènech i Montaner and Antoni Gaudí. We mustn’t forget that much of Barcelona’s success today is due to these three great men. They were people with ideas and men of action, of great civility, committed to a concept of their country which they expressed in great architectural works.

Puig i Cadafalch designed the four columns on Montjuïc to represent Catalanness (the present ones are a replica made in 2010). They were part of a plan to develop the area on the occasion of an exhibition on the electrical industry to be held in 1917, later replanned as the 1929 Universal Exposition. The columns were built in 1919 and demolished nine years later under the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera. The image shows the last column being demolished.

Photo: A. Gil / AFB

Difficult times

But if Josep Puig i Cadafalch has gone down as the forgotten president, it is, among other things, because of a mistaken political decision. It fell to him to preside the Mancomunitat at a very difficult time for our country, years of great social and political upheaval. It was the age of gun-toting gangsters, when people were killing each other in the streets of Barcelona. The Mancomunitat was overwhelmed in matters of law and order because of fierce social conflicts. And he had no powers in this sphere. What’s more, the spiral of violence was the antithesis of the spirit of the institution.

At the same time, another element that did nothing to help Puig i Cadafalch’s political legacy was the troubled relationship he had with other leading intellectuals taking part in the work of the Mancomunitat. Relations with the artist Torres Garcia were complicated, with the priest Mossèn Alcover they were difficult… and with the writer Eugeni d’Ors they were explosive!

Puig i Cadafalch obviously didn’t have the skill that characterised Prat de la Riba to surround himself with and direct such a powerful team as that formed by a large part of the country’s intellectuals (apart from the three already mentioned, the linguist Pompeu Fabra, the politicians Antoni Rovira i Virgili and the linguist Jordi Rubió and others all played an important part).

Having said that, Puig i Cadafalch’s work still stands, literally; both the physical work he himself conceived and signed as an architect, and the political work, which was planned by Prat de la Riba and which he executed.

Spiral staircase in one of the towers of the Casa de les Punxes in Barcelona, at the junction of Avinguda Diagonal, Carrer del Rosselló and Carrer del Bruc, a work from 1905.

Photo: Ramon Manent

More than a hundred years later, Barcelona can still boast Casa Amatller, on Passeig de Gràcia, Casa de les Punxes and Palau del Baró de Quadres, on Avinguda Diagonal, Palau Macaya, on Passeig de Sant Joan, the Casaramona factory, on Montjuïc, Can Serra, the home of Barcelona County Corporation on Rambla de Catalunya, Palau d’Alfons XIII and Palau de Victòria Eugènia, in the Montjuïc Fair area, and the four columns opposite the fountains on Montjuïc, replicas of the originals that were demolished by the dictator Primo de Rivera. As regards his contribution as a town-planner, we could mention his extensive remodelling in this same part of Montjuïc, as well as in Plaça de Catalunya, and the opening up of Via Laietana, while in Maresme – especially in his home town Mataró, but also in Argentona, Canet de Mar, Lloret de Mar…– his works still stand out and radiate a unique spirit of their own.

As a restorer of important monuments, he was in charge of the work on the Palau de la Generalitat (which was then the home of the Barcelona Provincial Corporation) and on the monasteries of Montserrat, Sant Joan de les Abadesses, Sant Benet de Bages and Sant Miquel de Cuixà, the Romanesque works of Sant Pere de Terrassa and La Seu d’Urgell cathedral, and he also directed the work of rescuing and restoring the Romanesque art in the Pyrenees. And as regards his work as an archaeologist, the excavations he directed at Empúries were especially important.

Bearing in mind all the work he did in different spheres and the building resources available at the end of the 19th century, we could say Josep Puig i Cadafalch was hyperactive.

Lobby of the Palau del Baró de Quadras, also on Avinguda Diagonal, which has been home to institutions like the Museu de la Música (Museum of Music) and Casa Àsia (Asia House), and now houses the Institut Ramon Llull (Ramon Llull Institute). Puig i Cadafalch built it between 1904 and 1906.

Photo: Ramon Manent

The work of the Mancomunitat

In addition, we must emphasise the public works promoted by the Mancomunitat, which are well known to everyone. The main ones are the Biblioteca de Catalunya (Library of Catalonia), the Escola Catalana d’Art Dramàtic (Catalan School of Dramatic Art), the Escola Industrial (Industrial College), the Escola del Treball (Vocational Training College, the Escola Superior de Bells Oficis (Higher College of Arts and Crafts), the Escola d’Infermeres (College of Nurses) and the Institut Cartogràfic de Catalunya (Cartographic Institute of Catalonia).

In the words of the historian Lluís Duran, ‘We know the Presidents of the Generalitat in the 20th century by their names. We know the Presidents of the Mancomunitat by their works’. In the same way, the journalist Francesc Canosa stresses that ‘all of the work of the Mancomunitat is still standing!’.

This enormous work, both personal and political, has been overshadowed by a serious political mistake Puig i Cadafalch made, which was not to oppose Primo de Rivera. An obvious mistake, but it should also be pointed out that no one opposed him. Political accounts of the time report no moves of any sort against the dictator. No one put up any resistance to him. The need to restore order in the streets, physical safety, was a priority.

Josep Puig i Cadafalch erred on the side of innocence when he believed that the dictator would respect the work of the Mancomunitat and the spirit of Catalanness that impregnated it. He later acknowledged his error and expressed his remorse over it. Puig i Cadafalch suffered reprisals on two fronts, suffering at first hand the political contradictions of the first third of the 20th century. He paid for it with a first exile when he resigned his post as President of the Mancomunitat in 1923, and with a second in 1936, at the start of the Spanish Civil War.

Puig i Cadafalch was one of the men of La Lliga Regionalista who not only didn’t acknowledge the Franco regime, but also opposed it from the first day. His work after presiding the Mancomunitat was in keeping with his political career, and during the early years of the Franco regime he was one of the most active representatives of the Catalanist cultural resistance. On his return to Barcelona in 1942, he devoted himself to the reconstruction of the Institut d’Estudis Catalans – IEC (Institute for Catalan Studies) in his home in Barcelona’s Carrer Provença, the same one where all the IEC records were discovered a few months ago behind a false wall he had built. Thanks to these records, it has been possible to follow the thread of the organisation from its foundation, to which he was a contributor, until the architect’s death. It was one of our country’s solidest cultural institutions, and after a period of clandestine activity during the Franco era, it was publicly resumed in 1979 following the return of democracy and self-government. A thread that should never have been broken.