La Barcelona dels tramvies i altres textos

La Barcelona dels tramvies i altres textos

[The Barcelona of Trams and Other Texts]- Edited by Jordi Amat and Agustí Pons

- Editorial Meteora and the

- Barcelona City Council

- Barcelona, 2015

- 240 pages

The editors of the work were religiously intent on vindicating Barcelona journalism, a school in which Luján is a leading figure. In terms of the author’s style, they stress the influence of the great school of journalism represented by Pla, but also by Sagarra and Camba.

The book is an anthology of Luján’s newspaper articles, divided into four chapters: a selection of articles on Barcelona that the author published in Destino under the title “Al doblar la esquina” [Around the Corner] (1946-1951); a selection of the obituaries he wrote between 1950 and 1981 for the same magazine; entries from a valuable 1947 journal; and, finally, “Apuntes para una futura historia del Premio Nadal” [Notes for a Future Story on the Nadal Awards].

In my opinion, the two chapters that sustain the book are the articles and journal. The obituaries, however, give nothing more than a sense of urgency, the requisite formulaic notes. Among the latter I would highlight the obituaries written for J. M. de Sagarra and Josep Pla. Two figures who are often cited in these pages, as one would expect. First thing’s first, however.

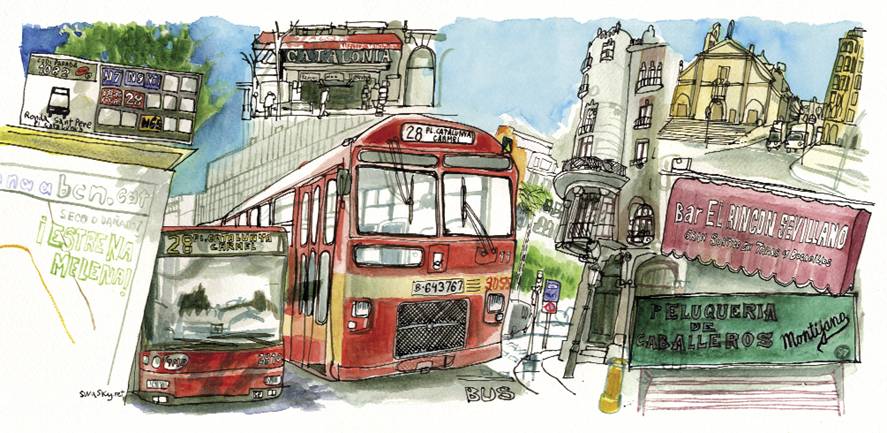

The editors of the work were religiously intent on vindicating Barcelona journalism, a school in which Luján is a leading figure. In terms of the author’s style, they stress the influence of the great school of journalism represented by Pla, but also by Sagarra and Camba. These articles from the “Al doblar la esquina” section were the result of perfectly localised issues, mainly those regarding the tram company (even so, the articles also criticise the city’s urban sprawl, the inconvenience of certain construction projects that dragged on, the proliferation of cockroaches in flats in L’Eixample, etc.). Biting and sharp, these are articles that should be taken lightly by those they criticise, because the author is often ironic: “We apologise for bringing up the issue of the tram company once again […]”

Formal man that he was, Luján writes of “the value of discipline in any aspect of life”, complains that Barcelona is “such a sad, messy city” (today, some of Barcelona’s journalists and writers complain that the city is touristified), uses a constant irony that often comes close to bitter sarcasm (as in “the reasons for the duration of the works […] force us to reach back to ancient Egypt and the pyramids to find another example of such a monumental effort”). However, some of these articles occasionally go beyond the framework of public criticism to seemingly embrace the Orsian theory of civility in general: see Luján’s magnificent “Volaron dos mariposas” [Two Butterflies Flew], an extremely short article that, in my opinion, should be included in any textbook on journalistic writing.

The 1947 journal begins with a reference to Josep Pla, who was the last subject of the obituaries in the second chapter. It is a splendid journal that demonstrates, much more than the rest of the selected works, that Luján was a great writer. It abounds with the names of the men who worked for Destino (Agustí, Vergés, Teixidor, Pla, Brunet); there are references to books, to bulls… The descriptions of individuals, especially their physical characteristics, are quite simply masterful: the face of a man has the “colour of twice-baked brick” and the face of a woman has skin “the colour of stomach”. The Pla he describes in the first pages is also exemplary: “Hypertensive hands, with thick veins and gleaming skin, like wax.” It sounds like Flaubert. Or Pla himself.