The first kiosks were built in Barcelona in the mid-19th century, either to sell products or shelter musical performances. However, the first newspaper kiosk was the initiative of an evening paper born in 1888: El Noticiero Universal. From La Rambla, newspaper kiosks spread throughout the city.

A crowd gathers around a kiosk on La Rambla at an uncertain date in 1908 to glance at the day’s headlines.

Photo: Frederic Ballell / AFB

Kiosks are much older than we might expect. The venerable linguist Joan Coromines tells us that the word is of Turkish origin (kyöšk). It originally meant a luxurious building for recreation and relaxation within a large garden with columns, often with a terrace or gallery and an open pavilion. This word passed through other languages, such as Persian, Pahlavi, Syriac, Aramaic and Arabic, and it reached us through French, which had incorporated it by 1624. Nevertheless, English, which is always more open to renewal and enrichment, had already done so one year earlier. Spanish didn’t accept the word until 1884, surprisingly allowing it to be written either with a “q” or a “k”, perhaps to reflect its exotic origin.

At the time, the Royal Spanish Academy defined it as a small stand for selling objects or for sheltering musical groups. No mention yet of the press.

It seems that in the mid-19th century a number of kiosks were placed in public spaces by both private and municipal initiative. Architect Garriga i Roca’s 1857 reform of the Pla de Palau included a kiosk for refreshments: a small, wooden structure with a single window.

In 1870, there were a number of requests to place kiosks across town, so the City Council asked the aforementioned municipal architect for a unifying project that would provide a minimum of decorum to so many structures. His design was in wood, reinforced with iron and with a zinc roof. The bureaucratic process was as slow as it always is, and the first wasn’t placed until 1877, on La Rambla.

The event, which made the news, inspired the city’s most enterprising residents. Miquel Coch, for example, presented a more ambitious and attractive project the following year. It was approved and built in the Plaça de Jonqueres. However, it didn’t stay there long: the reform that completed the creation of Via Laietana moved it to one end of the new Passeig de Colom.

A number of other temporary kiosks also appeared, such as the pretentious pavilions within the fairgrounds of the 1888 Universal Exposition, or number of simpler ones selling all sorts of wares to the avalanche of visitors.

Kiosk at the entrance to Carrer de Santa Anna, from an uncertain date in 1907-1908.

The first press kiosk on La Rambla was set up by El Noticiero Universal in 1888, the year of the Universal Exposition. Soon, these establishments spread across La Rambla, and from there to the Eixample and other areas of Barcelona.

Photo: Frederic Ballell / AFB

The first newspaper kiosk

The honour of setting up the first newspaper kiosk went to a brand-new paper offering news 365 afternoons a year: El Noticiero Universal. Up until then, the Diario de Barcelona had been the most influential paper, because of both its seniority and the lack of lasting competition. It was joined by El Correo Catalán in 1876, La Vanguardia in 1881, and La Veu de Catalunya in 1899. In view of the journalistic and social situation in Barcelona at the time, it’s easy to understand some of the circumstances shaping the events described in this article.

It’s no surprise that none of kiosks of the day were dedicated to selling newspapers. To begin with, they didn’t provide much of a business opportunity. For one thing, many readers of Diario de Barcelona had their papers delivered to their homes early in the morning. This service would later be perfected to a surprising degree by La Vanguardia.

Therefore, the newly created El Noticiero Universal came up with a number of innovations that were the result of the innovative spirit of the owner, his great initiative and notable personality. Francisco Peris Mencheta, originally of Valencia, was no newcomer to the world of press: he had been a member of the editorial staff of several papers in his hometown and in Madrid. He had, of course, begun as a stonemason, which drove many –out of ignorance– to interpret his initiatives as eccentricities. It is true that when the third and definitive headquarters of his newspaper were inaugurated, he himself climbed up on the scaffolding at 35 Carrer Roger de Llúria for the joy of sculpting the publication’s name on the façade himself.

Not long before, Peris Mencheta had foreseen that the most modern, forward-looking city in Spain was to be Barcelona, where preparations were already being made for the 1888 Universal Exposition. Besides this event, Mencheta’s prediction was based on the opening of the first railway on the Iberian Peninsula, the tearing down of the city walls and the colonization of the Eixample. Once he had made up his mind to come and compete in Barcelona, he decided to try creating an afternoon newspaper. That way, his publication could carry fresh new stories from the same day, while others could only carry yesterday’s news. It goes without saying that the absence of radio and television further shaped the state of the market, but it is worth mentioning that Peris’ brother Juan had stayed in Madrid, where he led the Mencheta news agency. Founded in 1882, it was the oldest in Spain. As a result, El Noticiero Universal had its own generous source of news stories.

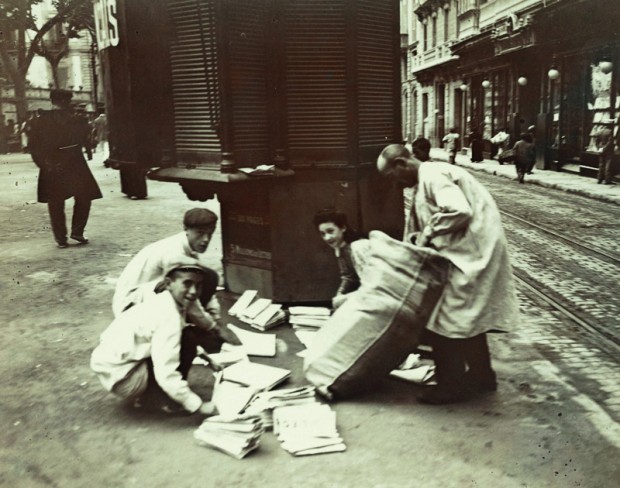

Kiosk attendants on La Rambla organizing their wares, in a photograph from 1907 or 1908.

Photo: Frederic Ballell / AFB

El ʼCiero’s new style

Three additional elements defined the new style El Noticiero Universal adopted from the very beginning.

First: the flock of vendors who would walk the streets carrying piles of newspapers, constantly shouting “El ʼCiero!” in imitation of the newsboys of foreign capitals. Now, when Walter Scott referred to the “youths with powerful lungs”, everyone understood the reference. I still heard an extended version of this cry soon after the Spanish Civil War: “CierooPe!” The new addition was a reference to La Prensa, another publication the paperboy offered passers-by. Aureli Capmany didn’t include these paperboys in his book on hawkers, although their way of selling their wares in the street would seem to merit it. When there was important news, the event became the focus of their cry. Meanwhile, the typical fair-style barkers didn’t last long, working within close proximity of their stores. Newspaper kiosks didn’t yet exist, and all some newspapers did was hang posters on the ones that did.

Second: as I’ve already mentioned, the creation of the first newspaper kiosk, built in Barcelona by El Noticiero Universal. It was related to an event that would have a significant and positive effect on Barcelona. On May 20, 1888, the Universal Exposition was inaugurated in a ceremony presided over by the royal family in the solemn venue of the Palau de Belles Arts. It was no coincidence that just a few weeks before, on April 15, the aforementioned newspaper had appeared, taking its stand in the afternoon battle. Going it alone was already a bold move. Plus, organizing the entire company structure to ensure speed allowed the publication to take full advantage of what was to be not only the first exposition in Spanish history, but also one of the most important events in the modern history of a city that had been used to bringing innovations to Spain and the West for centuries. It’s worth remembering the words of economic history professor Jordi Nadal, who declared that Barcelona is the only city in the world that has generated two revolutions: a commercial revolution in the Middle Ages, and an industrial revolution in the early 18th century.

Third: the location selected. It’s important to remember that this kiosk was a novelty; not for its size, design or decoration, but for its purpose. It was the first time one of the kiosks that were beginning to pop up around the city was used to sell press. In this case, basically just one newspaper: El Noticiero Universal. It certainly wouldn’t have been surprising if it had been placed within the fairgrounds of the Universal Exposition. However, Peris Mencheta (who had a nose for this sort of thing and a sense of the values of modernity, if we’re to believe his biographers) decided that the best place was on La Rambla. And he didn’t just build one kiosk, but four. Nevertheless, he didn’t create a new model, instead using one that had existed for some time in Paris.

It’s important to mention that these kiosks were meant to be permanent and not just to last for the few months of the Universal Exposition, which generated news every day. This seems extremely significant to me. Owner Peris Mencheta knew that kiosks weren’t just efficient resources, but an essential tool for the future of the press.

Over time, kiosks began to diversify in terms of both style and size. There were even “stairwell” kiosks that used the extra space in the entrances to apartment buildings to sell a little bit of everything. There are still a handful of very representative examples in Barcelona’s old city.

From La Rambla to the entire city

La Rambla soon became the spot for the best kiosks in Barcelona, to the point where they were as important as the flower vendors. Before long, they began to multiply. At the time, La Rambla was the heart of Barcelona; however, as the years went by and the Eixample was colonized, kiosks began to spread throughout the neighbourhoods and the housing developments that defined the outskirts of the city from the 1950s onward.

One of the tempting, unbeatable features of the kiosks on La Rambla was that they almost never closed. This was a characteristic of such a lively, intense city. My friend Valldeperas, the owner of Cafè Zurich, admitted to me that during the military uprising on July 19, 1936, he found that he couldn’t close his doors: he had none. The same thing happened to most of the businesses on Carrer Nou de la Rambla. When heading home late or leaving an event, until just a few years ago it was common practice to swing by La Rambla and buy a hot-off-the-presses copy of the newspaper.

Soon, some vendors learned how to enrich their business with their personality. There was Agustí, whose kiosk was on the Rambla dels Caputxins, also known as the Rambla del Mig. He was an anarchist from head to toe, and he never tried to hide it. So much so that when dictator Primo de Rivera was still the captain-general of Catalonia, he passed by the kiosk late one night after some illegal gambling to provoke its owner. He ended their debate with these words: “you’re a revolutionary, and one day you’re going to get it.” Agustí had managed to convert his kiosk into a hotspot for debate from eleven at night to three in the morning. His list of regulars certifies this fact, but I’ll only name a few of his most famous clients: Rusiñol, the Lerrouxists Emiliano Iglesias and the Ulled brothers, Casas, Nonell, the journalists Mir i Miró and Almerich; Opisso, Alarma, Peius Gener… and La Monyos.

The kiosks on La Rambla weren’t just attractive and unbeatable because they sold the day’s paper hot off the presses; they also had the foreign press and important French, German and English publications, bought by local artists to follow and discover the new styles Europe’s great artists were beginning to display.

During the long night of the Franco dictatorship, some trusted kiosks were the venue for discrete debates, providing opinions or stories that censorship kept out of the news. I was an onlooker at a debate my father participated in in the late ‘40s and early ‘50s at a kiosk on the upper side of what was then officially Avinguda José Antonio Primo de Rivera (Gran Via de les Corts Catalanes). It’s still there, moved a little to one side, and it’s been closed for some years as a result of having sold everything but newspapers without the necessary permits. The participants in this debate were the journalists Sempronio and Jaime Arias (he’d come by on his way to La Noti to see if there was anyone at the Ritz worth interviewing) and Rossend Llates (married to Maria Canals). The owner was named Tomàs, and he worked with his nephew Antoni Torres, a referee in Greco-Roman wrestling and a pillar of the Hot Club: he’d let me know when Armstrong, Hampton or Bechet were in town, so I could save up to attend the unforgettable jazz sessions they would organize.

André Maurois, Somerset Maugham and Georges Arnaud (author of the novel Le salaire de la peur, which Yves Montand starred in the film version, with cameos by painter and writer Joan Vilacasas and the great Picassian Josep Palau i Fabre) concurred on why the kiosks were the best part of La Rambla. Newsstands all around the world sold press and pornography, but the ones on La Rambla also sold all manner of books: poetry, novels, essays and history.

For five days in 1988 I had the privilege of showing Barcelona to Stephen Hawking, who was staying in the Ramada-Renaissance Hotel just off La Rambla. Once, when he went out –an extremely complicated operation– I shared the aforementioned reflection on the kiosks with him. Upon seeing one, he quickly made straight for it and looked it over, full of curiosity. In his first words to the press, he spoke of how pleased he was to see tall stacks of the Catalan- and Spanish-language editions of his book surrounded by magazines full of women displaying ample breasts.

The model for the current kiosks on La Rambla was created in 1972 by Pep Alemany and Enric Poblet, who were awarded the FAD architectural award that same year.

Photo: Pere Virgili

Design came late to kiosks: aesthetics wasn’t important. In 1972 Pep Alemany and Enric Poblet designed the ones on La Rambla, which received a FAD award. Those that would later spread throughout the Eixample and the rest of the city were the work of Antoni Roselló.

I’m saddened by the dangerous trend taking hold of our city: more and more kiosks are closing, and on Sundays it’s hard to find one open. Even worse, they soon degenerate into half-abandoned, dirty shacks that are stain on the urban landscape. We need an urgent solution that can help keep print editions alive.

It’s hard to imagine, but kiosks have even inspired poetry. Writer Osvald Cardona dedicated these lines to them: “paper castle / at one end of the square, / detains passers-by / like a man of strength.”