Nothing new is created without research, taking risks and teamwork. Gaudí knew this and became the manager of his artistic project. His attitude was identical to that of Einstein, Planck and Higgs.

© Pere Virgili

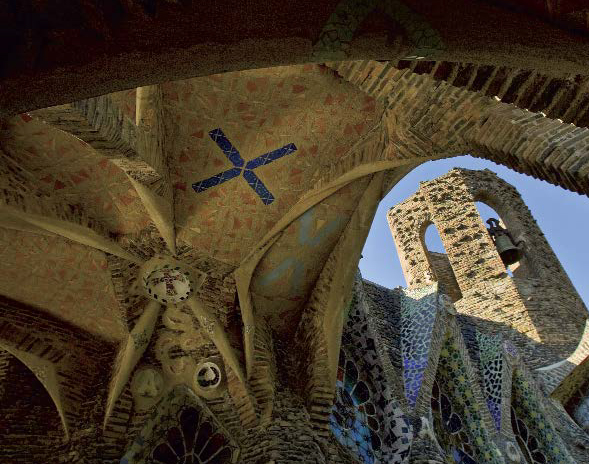

The four columns which support the ceiling of the crypt of the Colònia Güell and symbolise the four evangelists, are made with basalt pieces from Castellfollit de la Roca combined with lead. Gaudí always used local materials or materials from nearby areas, which is now a popular concept. The crypt was the first construction to make use of parabolic structure resistance.

Recent research on the work of Gaudí can be summarised in four points. The first indicates that Gaudí’s aim was to create a new kind of architecture; this is what made him original and revolutionary, and is the reason that after a hundred years it serves as a source of inspiration for today’s architecture and engineering. Second, the research establishes that what he had learned was of no use to him: he had to invent everything from methods and processes to equipment. His workshop was a laboratory where innovation and inventions were born. Third, he could not achieve his goals by himself; he needed a team, an interdisciplinary focus, and thus came up with the modern idea of managing mixed teams. Finally, the research concludes that the investment and creative partner that made his work physically possible was his friend Eusebi Güell.

Nothing new is created without research, taking risks and teamwork. Gaudí new this and became the manager of this project. “Should we call you a genius or a madman?” asked the president of the tribunal at the School of Architecture to a young Gaudí, who said: “There is no reason not to try something new just because no one has tried it before.” The same idea and the same attitude as Einstein, Planck and Higgs. Let’s have a look at some of his main contributions.

Father of light structures

Gaudí introduced the constructive use of twisted ruled surfaces (paraboloid, hyperboloid, hyperbolic paraboloid, conoid, ellipsoid and helical). Never used before, they enabled the building of structures and interiors that were larger, higher and more open, without external or additional supports, which makes them lighter, more functional and symbolic. In addition, these surfaces provide greater mechanical stability, require less material and can be built faster. Hence, Gaudí is considered the father of buildings based on lightweight structures, typical of sports halls, conference halls, train stations and any buildings designed to accommodate large numbers of people.

Gaudí created functional forms from based on geometry (“I calculate everything, I’m a geometer,” he said); such as inclined and double-twist columns, or intersecting combinations that are both functional and decorative. Structure, form and function merge. Geometric ratios describe and parameterise these structures: Jordi Bonet, chief architect of Sagrada Família for many years, says, “If you carefully examine the trajectory of the ideas and geometry and structural forms Gaudí used, you almost undoubtedly reach the same solutions that Gaudí had already determined, or the ones he surely would have come up with.” Starting with curves, Gaudí moves towards rationalism and contemporary architecture, which finds reasoning for solutions there.

Previously unheard of construction processes and materials, such as devising safer and more efficient scaffolding systems that were easy to assemble, with less material and that were also recyclable, as the planks made of different kinds of wood were reused for the construction of doors, frames etc. Building a structure starting with the façade or without load-bearing walls, anticipating modular and diaphanous architecture. The invention of trencadís, an ingenious technique for covering curved walls; durable, washable, made from recycled materials, serving as both decoration and covering: ceramic and glass pointillism transferred to exterior walls. All of these techniques are contributions to the new architecture.

Gaudí shared the spirit of his modernist colleagues in the use of new techniques and materials such as reinforced concrete, ironwork and electricity. He took them a step further thanks to his creative research and to the application of new ruled surfaces, in a fusion of structure, beauty and functionality, in an aesthetic line that would later be defended by Le Corbusier. He thus became a pioneer of expressionism, brutalism and architecture that is organic, efficient and makes use of recyclable materials.

Work method

© Pere Virgili

Model to scale 1:25 of the church of the Colonia Güell, which Gaudí never finished, produced by the Chair of the History of Construction and Architectural Heritage of Innsbruck University.

Gaudí’s work method is what today we would call co-working and co-design. In other words, working in multidisciplinary teams, based on research and innovation, both in terms of systems as well as structures, materials and ways of working, with a clear commitment to science. For its time, this was something extraordinary.

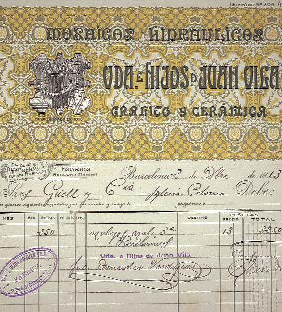

Gaudí rejected improvisation outright, calling himself a “meticulous bugger”. Simultaneously architect, artist and manager, he took on the planning, building and business aspects of his work. The proof: thousands of documents from Gaudí that outline both the cost and planning of the work. The example: almost half a century before the Japanese invented “just-in-time” and it was taught in business schools, Gaudí applied this technique to the management of orders, warehouse stock and building processes, with the aim of achieving efficiency in the work and financial effectiveness. Everything was well-planned and documented.

Gaudí’s method made it possible to invent the required technology, tools and materials, if they did not already exist, just as companies committed to R&D&I do nowadays. And when something already exists, it gets reused. Some examples include:

— The polyfunicular model as a system to represent and calculate the force loads of a building in a structural way, to scale and in three dimensions, before plans are drafted, as do many of today’s architectural firms. It was a precursor to Autocad, which combined with high-resolution photos obtained by manipulating the chemical formula of the flash, which when implemented in a viewer rendered a three-dimensional image and enabled, for example, the urban impact of a building to be seen before it was built.

At Moscow Polytechnic, they explain that it is difficult to understand that Gaudí, using only models, was able to perform the same calculations that are now done on supercomputers. Moreover, Arnold Walz studied Gaudí when developing 3D geometry processes for architectural design.

© Vicens Vilarrubias

Inverted polifunicular model – based on ropes or chains – in the same church, a system for calculating forces which inaugurated the Gaudian architectural revolution.

— The invention of trichromy. Combining data from astronomical observations, annual sunshine amounts and optical physics, Gaudí obtained natural light with multiple shades by layering three glass plates treated with primary colours. He covered the glass with stencils that left some areas open and others protected, and poured on liquid hydrofluoric acid, which diminished the tone of the colour in open areas, until he reached the desired degree. The bell shape of the windows made it possible to capture the desired amount of light. He thus achieved the effects of colour, luminosity and reverberation that he wanted for each place and each time of the day. For Gaudí, light and colour were key elements in giving architecture a symbolic value of life and beauty.

— Recycling. Gaudí spent when spending was called for and saved when saving was required. He used a chair leg to replace a broken handle, while also ordering light bulbs to be sent from the United States and Kern precision compasses from Switzerland. He was an amazing teacher of recycling, a radical precursor of Arte Povera. He recycled whenever there was an operational, practical and, furthermore, artistic reason for reuse. Thus, he collected refuse from tile makers and foundries for the ductile, light and thermal walls of the Colònia Güell church; wood from loom crates and steel bands from cotton bales from a nearby factory – an authentic local product, with near zero transport costs – to make benches that were beautiful and mechanically ultra-resistant, both owing to their materials and because the lower section was parabolic (perhaps the first place where this form was tried). Very economical at the time, today it is valued at €370,000 at auction.

© Vicens Vilarrubias

The crypt of the Colònia Güell under construction in the year 1910. The architect invented a cheap, efficient and easy-to-assemble scaffolding system, based on the recycling of materials.

Collaborators and apprentices

Gaudí had no disciples, but he did have colleagues and apprentices. That’s why he did not create a school. He worked with a team to invent, not to copy. He wanted the best of each trade for each job.

Work was collaborative and Gaudí repeated that it was necessary to listen and ask those who knew the most, starting with the mason and carpenter at each site. He must have been history’s first co-architect. “If I have an idea,” he said, “Jujol [architect, designer and artist Josep Maria Jujol] or Cudós [artist

Tomás Cudós] will be able to find the right colour.” If you look at Park Güell, you’ll only find one signature, and it’s not that of Gaudí.

Beyond. If you had to invent a way to get coloured light from sunshine – and stained glass artist Louis Comfort Tiffany had failed here – you’d have to find specialists from outside the building trade – physicists, astronomers, opticians, chemists, musicians, dynamiters – and work on it scientifically. To our knowledge, Gaudí is the first to use/create a laboratory for testing materials, which he did at the Industrial University of Catalonia.

Each material – such as the 47 types of wood we have identified at Colònia Güell – was studied and chosen based on ductility, resistance, functionality, use, beauty and position.

Sketch by Gaudí for the initial studies for the design of the church of the Colònia Güell.

Purpose, mission and context

Gaudí’s intended objective was to make a rational kind of art, at the service of the people (which is why he said that to create a work, first comes love and then technique). An art, therefore, that is both functional and imbued with life, full of colour and movement, inspired by solutions, shapes and colours drawn from nature, that is perfect and from which the values of beauty, humanisation, efficiency, ergonomics, usability and recycling derive.

Two curious examples: a seat tailored to a woman’s buttocks, who sat on soft plaster to create the mould, and the design of the box where a cord runs through four cylinders to make a rattle turn, which he made thinking of a left-handed bell ringer. What could be more ergonomic?

Symbolism and beauty are his mission. Creating works that achieve the ideal of beauty, defined as the radiance of the truth. Hence the use of local materials, the widespread use of recycled materials and even refuse, the integration with or reference to nature (the crypt in the forest or tree columns), the human scale or of the environment (the height of the Sagrada Família, below the highest point of Montjuïc) and symbology (in the classical, historical or popular tradition).

The most beautiful example is perhaps represented by the leaning basalt columns from the crypt at Colònia Güell. Pere Viñas, the apprentice, confessed to him: “I don’t like them. They are rough, cracked and I don’t understand them.” Gaudí was pleased by the interest and explained the structural function of the leaning column – like someone who leans on a cane – and read him a passage from Exodus where Moses asks God not to curse the stone by working it to make him a temple. We would not know all this, or we would engage in speculation, if Manuel Medarde had not done anthropological research and found Gaudí’s workers and their descendants, uncovering a hidden treasure: the diary of one of his apprentices, explaining in detail the daily life of the master, how he thought, worked and why he did what he did. Exciting.

His art integrated in an absolute manner tradition, the current trend and inventiveness of the avant-garde, Catalan national consciousness, social concern and religious yearning. A case that summarises this: the use of the flat brick vault. Inherited from popular tradition, in it Gaudí saw extraordinary functional possibilities (larger spaces, daylight openings, etc.) in combination with the ruled surfaces he invented. Artists are individuals who can take what is around them and turn it into something new. From the New York architecture of Guastavino to Otto’s Olympiastadion in Munich and Candela’s Sports Palace in Mexico, right up to Isozaki’s modern Convention Centre in Qatar, the ruled surfaces, with trees and in the Catalan tradition, are traceable, identifiable and obvious. Isozaki believes that Gaudí’s embrace of the modern broke the formal limits of known architecture.

A place for research

All of Gaudí’s research was done in the Colònia Güell workshop, and later in the Sagrada Família workshop. A real laboratory mimicking Edison’s Black Maria studio; a wonderful place where Güell said he was delighted with everything Gaudí did regardless of what he did, how long it took or the cost. The dream of every artist. The Colònia was, in Gaudí words, the place for research and innovation, for trying out everything you could imagine: “Without having carried out the tests I did at the Colònia, I would have never dared to apply it to Sagrada Família.” There he engineered the bulk of his revolutionary innovations, from design to the constructed reality: the polyfunicular model, the leaning pillar that follows the direction of thrust, the tree structure, the wall surface folded in parabolic shapes…

Colònia Güell is also atypical, a triple model of artistic, architectural and scientific revolution and technical-industrial innovation, social and cultural revolution (education expert Xavier Melgarejo wrote: “I was seeking a model of educational success in Finland, and in the end I’ve had it right here all along, and for the past 100 years.”)

The goals are always, first of all, practical and social: for Sagrada Família, because the client was not in a hurry, the first thing that was built was the school for the workers’ children, that humble building made of bricks that outlined the conoids that amazed Le Corbusier. At the Colònia, the factory, houses, school, the cultural centre, etc. – everything that was essential – came first. And after Gaudí had made houses of men, he designed the house of God, the work that would open the door to new architecture, built when he was in no hurry or under no pressure and could be the consummate artist.

Bear this in mind: the revolution in the history of architecture, which began with this avant la lettre calculator that is the polyfunicular model, was built with a never-before seen team: a mason, a teenage apprentice and an engineer. This will be helpful in discovering how to do calculations that had never been done before (the architect-engineer team is common today, but we have no evidence of it before Gaudí); the other person will be an effective apprentice and, because of his age, a polite troublemaker who will ask about what is so new and strange when nobody else would dare to do so. And the mason because he holds in his hands all the construction traditions that work well, due to the passing on of experience,.

© Pere Virgili

A corridor which goes through the entire lower part of the crypt of the Colònia Güell, built in the shape of a hyperbolic paraboloid, which Gaudí created as a resonance box for the organ and which also contributes to the climatisation of the building.

Health, hygiene and safety

I was not very surprised that those most interested in the findings of the research were businessmen and professionals, even more than historians and architects. They asked me to give a talk. When I finished, a man approached me and asked if I knew who he was and what he did. I said no. “I work in the area of ISO quality and hygiene certificates at work, and you’ve just said that Gaudí did the same job as me!” Yes, Gaudí established safety, quality and hygiene standards when they were not very important. And he was harsh if standards were not met.

A few examples: Gaudí made the women working in the Colònia textile mill work sitting down, not standing up, to prevent spinal column injuries. He also had them wear hair nets to keep their hair from getting caught in the machines, a common workplace accident. In construction, Gaudí watered the ground to avoid having people breathe in dust, and scheduled breaks to eat and made cleaning yourself mandatory. He offered advice on walking and getting sun, diet and instructions from Abbot Kneipp, and he encouraged workers to play sport (thus one of the facilities at the Colònia was… a football pitch).

Air, water, light, colour, sound

It is relatively easy for an architect to endow a building with natural light. It was even easier for him, as he applied the ruled surfaces. Now, how can life and movement be given to a building, which by definition is static and heavy? Gaudí recreated nature because nature is movement, the expression of life. He achieved it through a combination of materials and their irregularities, through the orientation of the building, curved shapes, the optical treatment of colour and natural integration, etc.: his buildings become changeable, and sometimes volatile, to erase the constructive limits when light and colour changes shape the spaces.

More constructive physics: through his choice of materials, in the ventilation systems (such as those provided by false columns that are actually chimneys, which, due to a Venturi effect, suck in and refresh the air, forming a sort of natural air conditioning with no energy cost) and drainage (pits, elevated floors, ventilation tunnels, water collection systems that were used for irrigation, etc.), Gaudí was able to regulate temperature variations and the level of humidity between indoors and outdoors (just imagine the savings on heating that enables). This combination of ventilation, drainage, natural lighting and the choice of materials forms a real system of ecological sustainability and energy efficiency.

© Pere Virgili

Bars made with pieces repurposed from textile machinery from the Colònia Güell.

Thanks to the study of physics applied to construction, the use of natural forces complements Edison’s research on electricity, when this was in the midst of commercial expansion. Examples that open up horizons: Gaudí designed a cinema, taking into account lighting and the transmission of sound and live music (none of Gaudí’s buildings echo). In terms of acoustics and music, the most spectacular thing to point out is that the towers of the Sagrada Família are belfries with enormous tubular bells, shapes he had previously tested in miniature, in a Wagner opera at the Liceu. And from the largest to the smallest: the rattle (wooden percussion wheel) at Colonia Güell is a marvel in choice of wood for producing sonic scales, while also being a symbol of factories as it mimics the sound of looms operating.

Business and social innovation

Artistic, technical and process innovation are inalienable assets of the Güell Gaudí binomial.

Güell, the patron-businessman, and Gaudí, the politician-creator, established a relationship of mutual influence. In other words, a genuine co-working situation that provided artistic challenges, business opportunities, as well as civic, national, social and worker engagement, based on innovation and design.

This unusual way of working, combining business, social needs and innovation in order to create something radically new, did not become an artistic, political or economic pillar, but instead remained on the sidelines, in an industrial village that was a social model and unique for its design. Consider, then, creation and industry – in close proximity and interconnected – as complementary factors of growth.

At the top, the four columns which support the ceiling of the crypt of the Colònia Güell and symbolise the four evangelists, are made with basalt pieces from Castellfollit de la Roca combined with lead. Gaudí always used local materials or materials from nearby areas, which is now a popular concept. The crypt was the first construction to make use of parabolic structure resistance.

Model to scale 1:25 of the church of the Colonia Güell, which Gaudí never finished, produced by the Chair of the History of Construction and Architectural Heritage of Innsbruck University.

Sketch by Gaudí for the initial studies for the design of the church of the Colònia Güell. On the right, inverted polifunicular model – based on ropes or chains – in the same church, a system for calculating forces which inaugurated the Gaudian architectural revolution.

A corridor which goes through the entire lower part of the crypt of the Colònia Güell, built in the shape of a hyperbolic paraboloid, which Gaudí created as a resonance box for the organ and which also contributes to the climatisation of the building. At the foot of the page, bars made with pieces repurposed from textile machinery from the Colònia Güell.

The crypt of the Colònia Güell under construction in the year 1910. The architect invented a cheap, efficient and easy-to-assemble scaffolding system, based on the recycling of materials.

The Colònia Güell is the star of the Gaudí 1st World Congress

The Gaudí 1st World Congress, organised by the Gaudí Research Institute with the collaboration of the University of Barcelona (UB), is to be held from 6-10 October 2014 with the aim of sharing research as well as industrial and creative applications.

The Gaudí 1st World Congress, organised by the Gaudí Research Institute with the collaboration of the University of Barcelona (UB), is to be held from 6-10 October 2014 with the aim of sharing research as well as industrial and creative applications.

As the first in a series of conferences, this one will focus on the Colònia Güell as the seed of Gaudí’s creativity, the place where he installed the laboratory in which a new architecture based on a revolutionary method of work and creation of new forms was born.

Although the symposium focuses on the Colònia Güell, this is not the sole subject matter. Other activities include the presentation of the English translation of philosopher Carles Rius Santamaria’s work Gaudí i la quinta potència. La filosofia d’un art, published in 2011 by UB and the Barcelona City Council.

This first edition honouring the Colònia Güell will have the participation of Arata Isozaki, Rainer Graefe, Jos Tomlow, Arnold Walz, Manuel Medarde, Jan Molema, Etsuro Sotoo, Carlos Flores, Tokukoshi Torii, Antonio Sama, Leonid Demyanov, Arnau Puig, Ferran Adrià and others. The riveting challenge: to transform Barcelona into the research and innovation capital of the master with the most World Heritage sites under his belt.