The Publishers’ Guild of Catalonia (GEC) brings together 279 publishers who put out more than 30,000 titles each year. The industry is now facing the challenges of the economic crisis, the new global market, the technological revolution and a shift in reading habits: challenges that seem perfectly manageable for an industry backed by five centuries of history.

Barcelona is among the cities in the world which boast a long, uninterrupted publishing history. From the dawn of the printing press to the present day, it has been producing volumes for a very broad reading public over the last five centuries. This uninterrupted vocation is a defining feature of the Catalan metropolis, which has been and remains the publishing capital of Spanish America.

How has Barcelona come to be a key leader in the international cultural industry?

In the Middle Ages, the city already possessed what might be called a complete literary ecosystem. There is evidence dating back to the 11th century of the circulation of copies of religious and legal works. The historian J.E. Ruiz-Domènec has pointed out that the counts of Barcelona (as well as kings of Aragon from the 12th century) sought to strengthen culture through books, promoting the Floral Games and embracing writers such as Bernat Metge, author of Lo Somni [The Dream]. At the same time, figures close to the court, such as the aristocrat Bernat Tous and the archivist Pere Miquel Carbonell, created magnificent libraries.

Another scholar, Joan Batista Batlle, recounted that Barcelonian booksellers in the Middle Ages were occupied with providing wealthy clergy members, jurists and merchants with copies of books for each stratum of the old social hierarchy. Their collaborators were scribes, illuminators of letters (embellished initials, known as caplletres in Catalan) and xylographists. Ordinances for booksellers proclaimed by municipal consellers in 1445 represent the first instance of institutional recognition in the Iberian Peninsula of the importance of the guild. A street near the city’s mediaeval centre would later be christened Carrer de la Llibreteria.

In this environment of promoting the written word, it is not surprising that, a few years after Gutenberg launched his universal invention, German craftsmen such as Enric Botel and Pau de Constanza settled in Barcelona and organised the first regularly operating printing workshops in Spain. From the eighties on, editions in Latin, Catalan and Spanish emerged from the Barcelonian presses. The scholar Pere Bohigas has cited a translation into Catalan of Cárcel de amor [The Prison of Love], from 1493, printed by Rosembach; Histories e conquestes [Tales and Conquests] by Pere Tomic, (1534); and Antiquiores barchinonensium leges, quas vulgus usaticos appellat, from 1544, as being among the period’s loveliest books.

A few dozen kilometres outside of the city, the printing press at Montserrat monastery issued its first volume, Liber meditationum vitae domini [The Book of Meditations on Life] in 1499. Although it has suffered a number of interruptions throughout its history, the abbey’s publishing house remains active today, rendering it Europe’s senior publishing house.

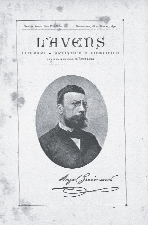

Arxiu de Revistes Catalanes Antigues

Cover of L’Avenç, from February 23rd 1890, with a photograph of playwright Àngel Guimerà.

Don Quixote in the workshop

There is a key literary episode that sheds light on Barcelona’s publishing vocation. When, at the beginning of the 17th century, Cervantes sent Don Quixote to Barcelona in the final chapters of the second part of his novel, he had him enter a printing house, presumably inspired by that of Sebastià de Cormellas, where he carried on meaningful conversations with the printer and an Italian author. Cervantes thus cast the Catalan capital as a city of books in the international literary imagination.

The Catalonia of the 17th and 18th centuries kept up a constant output of religious books, texts, professional treatises and literary works. Latin withered and Spanish bloomed: an abundance of classics were published in Barcelona for the rest of Spain. Production in Catalan decreased considerably and was sustained primarily through didactic works, pamphlets and chapbooks. To understand this period, and the subject matter at hand in general, it is essential to read Manuel Llanas’ Història de l’edició a Catalunya [A History of Publishing in Catalonia].

Often, printing workshops associated with bookshops are a family business passed down from one generation to the next. Such is the case of the Martí, Surià and Piferrer printing dynasties. The Piferrer workshop printed Catalonia’s most visually outstanding work of the 18th century, La máscara real [The Royal Mask]. The work was commissioned by the Barcelonian guilds to celebrate Charles III of Spain’s arrival to the city in 1759, and describes the festivities held in his honour.

The historian A. Duran i Sanpere reconstructed the operations of the Piferrer family business from a set of preserved invoices. Theirs was a “costal trade”, with expeditions to several cities along the Mediterranean, from Alicante to Seville. Maritime shipments of books were made “by means of polaccas, feluccas, pinks, tartans, sailboats, canaries, xebecs, brigantines, sloops and other watercraft”. They were governed by sponsors from Palamós, Valencia, Sant Feliu, Malgrat, Mallorca, Dénia and Barcelona. “Books”, Duran added, “were transported in bundles, bales or packages, or wooden boxes if they were bound”.

This century witnessed a flourishing of institutions of high culture devoted to the world of books in Barcelona, such as the Reial Acadèmia de Bones Lletres [Royal Academy of Letters], with its meetings of scholars and historicist publications.

Thanks to the invention of the flatbed press at the beginning of the 19th century, printing became faster and books consequently became less expensive. Antoni Bergnes de las Casas was by all accounts the first modern publisher in Catalonia, with works such as an impressive Diccionario geográfico universal [Universal Gazetteer] in ten volumes published between 1830 and 1834. Bergnes was also the director of magazines such as El Vapor, in which Aribau published the poem “La pàtria” [Ode to the Motherland] (1833), which is considered the starting point of the Renaixença.

Throughout the century, numerous figures in the book industry floated between a publishing world that set its stakes on Spanish-language output, and support for or simultaneous complicity with a Catalan literary renaissance, which would largely focus its energies on the region’s intelligentsia. The strength, technology and resources of the Spanish publishing industry would help get the Catalan publishing industry off the ground.

Biblioteca Digital de Castilla y Léon / Wikimedia

The Alcazar gate in Avila, as it was portrayed by Francesc Xavier Parcensa in Recuerdos y bellezas de España, published in 1865.

Joaquim Verdaguer was a contemporary of Bergnes de las Casas, who brought to bookstores the famous twelve-volume illustrated series Recuerdos y bellezas de España [Memories and Beauties of Spain], with prints by F. X. Parcerisa. Narciso Ramírez and Francisco Oliva were also among the period’s distinguished publishers. Some divided their time between publishing and bookselling.

In the century’s final decades, a few strong, powerful publishing houses with their own vessels and printing presses established themselves. This marked publishing’s transition from the romantic period to the industrial period. These companies bore names that would reach legendary proportions, such as Montaner y Simón, Salvat, Heinrich and Espasa. The owners and directors often travelled through Europe to become familiar with new printing systems, incorporate translations into their catalogues and participate in international guild meetings in Paris, Brussels, London and Leipzig. Barcelona positioned itself as a publishing leader in the Spanish-speaking world with its constant exports to the Americas and establishment of offices and subsidiaries there.

In the second half of the 19th century, several publishers systematically printed in Catalan, which received a fresh boost as a language of culture after three centuries. The literary Renaixença had its practical correlative in printing presses such as L’Avenç and La Ilustració Catalana, tied to magazines of the same names.

In 1897, Josep Lluís Pellicer and Eudald Canivell founded the Catalan Institute of Book Arts, with the twofold aim of lobbying for the publishing industry and training professionals in techniques such as photoengraving, stereotyping and composition.

Turning point in the 20th century

The Barcelona of the first third of the 20th century was a city that modernised at full tilt, seeking to emulate the major European metropolises. Bookselling activity reached a turning point: By Antoni Palau’s account, in 1933, there were more than 50 second-hand bookshops in the city.

These were years of major projects: following the example set by the major German leaders, the Espasa publishing house launched its Enciclopedia, which would end up totalling 82 volumes of 1,500 pages each, with a weight of 164 kilos and a length of six linear meters. Notably, Espasa – which published in Spanish – recruited its editors amongst some of the most distinguished figures in Catalan nationalist culture at the beginning of the century. Its collaborators in literature and graphic design included the likes of Miquel dels Sants Oliver, Jordi Rubió i Balaguer, Pompeu Fabra, Josep Comas Solà, Alexandre de Riquer and Ramon Casas.

Different publishing houses reveal the maturity of the Catalan-language market: Barcino, Editorial Catalana, Llibreria Catalònia, etc. Edicions Proa, founded in 1928, launched the A Tot Vent book collection, which published classic European novels (Dostoyevsky, Proust) alongside works by young local authors (Benguerel, Rodoreda) and new international figures (Moravia). It ultimately sold around a million copies of its titles. The politician Francesc Cambó strongly encouraged translations of major classics through the Bernat Metge Foundation.

In the realm of popular literature, the publisher Molino launched successful mystery and detective collections. The Montseny-Mañé family, who adhered to an anarchist ideology, was behind the La Novela Ideal [The Ideal Novel] collection, which put out 600 volumes exceeding 10,000 copies.

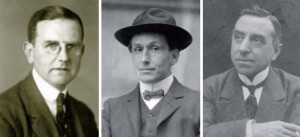

AFB

Philologists Jordi Rubió i Balaguer and Pompeu Fabra, in portraits from the second decade of the last century, and Josep Comas i Solà, director of the Fabra Observatory, in 1902. These were three of the foremost representatives of Catalanist culture in their time, and all three participated in the Spanish Encyclopedia Espasa.

The reign of King Alfonso XIII saw the start of a publishing-association movement in Barcelona, and the city’s Chamber of Books was founded in 1918. In the course of its history, José Zendrera, the founder of Editorial Juventud, and his colleague Gustavo Gili – both very important editors in their own right – would tirelessly support all sorts of guild initiatives, encouraging the different governments to undertake measures to protect their industry.

Taking up the initiative of Vicente Clavel, a Valencian publisher and journalist residing in Barcelona, in 1926 Primo de Rivera’s administration approved the creation of a book fair that initially was held on 7 October, but was moved to 23 April in 1930. In Catalonia, the fair quickly merged with the festival of Sant Jordi to the point that the two occasions became inseparable.

In the years of the Spanish Republic, various publishing houses (Àgora, Juvenal and Bauzá) published oppositional or openly revolutionary literature from Barcelona. The Spanish Civil War had a destructive effect on the Catalan publishing industry (which, nonetheless, did not halt production) and on the city’s intellectual fabric. After the conflict came to an end, many members of book industry faced censorship, saw their activity restricted or followed the path of exile.

Post-war period

Under the post-war dictatorship, the Catalan language was reduced to a semi-clandestine status in terms of literary creation and publishing. At the same time, several star Catalan publishers laid out a trajectory that would mark the Spanish culture of those years.

After forming part of the intellectuals of the Franco regime who were the driving force behind Destino magazine, Josep Vergés launched, through the publisher of the same name, the Nadal prize, which would attract a loyal following. Vergés was also the legendary publisher of the definitive complete works of his friend, Josep Pla.

Josep Janés i Olivé, who had raised spirits in antebellum Catalonia with his Quaderns Literaris [Literary Papers], set about publishing in Spanish with a specialisation on British narrative. (Following his death, the José Janés publishing house was acquired by the Plaza publishing house, giving rise to Plaza & Janés, the great generalist publisher from the sixties on.)

In the fifties, José Manuel Lara, an Andalusian transplant to Catalonia, promoted his publishing house Planeta, with major hits such as Josep Maria Gironella’s trilogy on the Spanish Civil War (Los cipreses creen en Dios [The Cypresses Believe in God] Un millón de muertos [One Million Dead] and Ha estallado la paz [Peace After War]) and translations of bestsellers by authors such as Frank Yerby and Frank G. Slaughter. These authors would soon be awarded the famous Planeta prize for novels, which competed with the Nadal prize from the publisher Destino and very quickly exceeded it in terms of prize money.

The publishing company Bruguera founded a major factory of pop dreams, an entertainment industry that unfolded with the production of comics and dime-store novels with themes on the Wild West, romance (with Corín Tellado’s major successes) and adventure, as well as literary adaptations and pocket classics.

Carlos Barral, at the helm of the publisher Seix Barral, represented modernity and experimentalism. He would be the main driving force behind the key phenomenon of the literary boom in Spanish America in the sixties. Seix Barral awarded accolades to novels by Mario Vargas Llosa, Carlos Fuentes, Guillermo Cabrera Infante, and others. Some of these authors would go on to be represented by the agent Carme Balcells. Vargas Llosa and García Márquez moved to Barcelona, the literary boom spread internationally from the Catalan capital and its publishing prestige was etched into the history of the 20th century. The contributions of these and other publishing houses allowed Barcelona to remain the Spanish-language capital of books in the midst of the Franco regime.

In Catalan, J.M. Cruzet and his publishing house Selecta kept the flame burning until in the more permissive sixties new publishing houses came about that captured the modernity of the time, particularly Edicions 62. Under the literary direction of Josep M. Castellet, this publishing house forged ties with new European trends in the fields of narrative – Catalan and international – and the essay. The Gran Enciclopèdia Catalana [Great Catalan Encyclopaedia], which was first published in 1968, symbolised the Catalan language’s recovery and cultural and economic steps forward. In this decade, Club Editor, driven by its merger with Sales, published some of the masterpiece Catalan novels of the 20th century (by Rodoreda, Villalonga and Sales himself).

In the years leading up to and following Franco’s death, Barcelona experienced a creative explosion. Publishing houses such as Anagrama and Tusquets, which hailed from the anti-authoritarian left, established themselves by publishing counter-culture works, new journalism and anti-conventional narrative. Catalan publishing also experienced a revival, and very soon names such as Llibres del Mall, Quaderns Crema and Columna emerged. Bookshops committed to the cause invested in disseminating voices on the political and social change taking place.

At the same time, Planeta started to take over former rivals such as Seix Barral and Destino, and consolidated its identity as a publishing empire in an expansion process that would lead it to become the world’s eighth-largest publishing house in the 21st century.

Barcelona became a field of operations for multinationals in the book industry, which used the city as a platform to access the Spanish American market. The first to arrive, in the sixties, was the German publisher Bertelsmann, which launched the very successful Círculo de Lectores, and later on merged with the Italian publisher Mondadori and then the British publisher Penguin.

In recent decades, Barcelona has published fewer books per year than Madrid (which holds the title of textbook capital), but thanks to its greater revenue, it remains the industry leader. New publishing houses such as Salamandra and La Campana help maintain the spirit of innovation. Jaume Vallcorba, the owner of Quaderns Crema, founded the Spanish-language publisher Acantilado, a major cultural leader that has revived classic works. Other groups such as RBA and Océano maintain their head offices in the city.

To spread the notion of Barcelona as a city of books and publishers, the city council declared 2005 as the Year of Books and Reading, and developed a programme with more than 1,500 activities. In October 2007, Catalan culture was the guest of honour at the Frankfurt Book Fair, the world’s top annual meeting for book professionals.

The Catalan publishing world would not be what it is without literary agents, which has no shortage of outstanding women. The most important historical figure is Carme Balcells. Her colleagues in active service include Mercedes Casanovas, Antonia Kerrigan, Anna Soler-Pont (Pontas), Mónica Martín, Silvia Bastos, Sandra Bruna and Guillermo Schavelzon. Another indisputable touchstone in the industry is Pompeu Fabra University’s Master in Publishing and Editing. Directed by Javier Aparicio, the internationally recognised programme has now been running for 20 years.

Currently, the Publishers’ Guild of Catalonia (GEC) brings together 279 publishers who put out more than 30,000 titles each year. The industry is now facing the challenges of the economic crisis, the new global market, the technological revolution and the shift in reading habits. But for an industry backed by five centuries of history, these challenges seem more than manageable.