We have to ask ourselves what gives the authors of the new Catalonia tourist campaign the right to so willingly give away the region to outsiders.

Let’s lay our cards on the table. If it were not for tourism, I would not be here writing this article. I am the son of hoteliers and the grandson of bar owners, on both sides. At home, I probably would not have experienced the opening up of horizons that the arrival of northerners brought about; I most likely would not have had an Italian girlfriend, and therefore trips to Milan; my parents probably would have not been able to pay for my studies. Without this business, the wealth of the Costa Brava would surely not be so dissimilar from that of the small inland villages, with less tourism.

Or maybe it would. Maybe some other type of industry would have sprung up, just as unexpected and prosperous as the cork industry once was. Who knows? People look for ways to make a living, and it often happens that one plant obstructs the growth of another. Let’s not waste time on this however, because in any case it’s too late: things are the way they are, with everything that entails, and I myself have experienced the way things are, which is why I can say a thing or two about the matter.

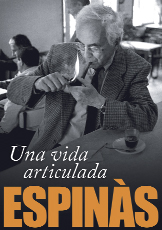

More than fifty years ago, the jourmalist and writer Gaziel was sat on the stone bench of a viewpoint as he contemplated the bay of Sant Feliu de Guíxols, asked himself: “Should we treat the outsiders who come here from around the world like friends or like passers-by? Should we charge them honestly for our services, or try to empty their pockets the quicker the better?” This is an article dating from the year 1960. Gaziel had debated questions regarding tourism previously in his book on Florence, from the point of view of the traveller. Now he was dealing with the matter from the locals’ point of view, and he was shrewd enough to foresee the scope of the issue.

It was during the 60s that my grandfather, who worked in the transport business when horses were still used, had the idea of opening up riding stables in Platja d’Aro, the village next to Sant Feliu. It was a typical example of what many people in the area did. The riding stables lived off tourism, naturally, and he was soon able to add a bar. Then, above the bar, some rooms, which in the eighties were turned into a hotel. I was born sometime in between, and the first job I ever had was stocking the fridges with soft drinks and refilling the boxes with empty glass bottles. Another was to lead horses by the reins under the hot summer sun for thirty minutes or an hour around the ring, pulling along a foreign child mounted on the horse. Working for a child. Later, when I was a teenager, I got to ride the horse and act as a guide, and later still I was the hotel receptionist during those long nights. These are ideal jobs when you’re studying.

I want to tell a story that has do to with the questions Gaziel asked himself fifty years ago. My grandfather, who ran the stables, always encouraged me to wait for a tip from the customers. It is a sad and humiliating culture, that of tipping, but for a child… well, you know what I mean. He encouraged me to hold my hand out. To uphold my dignity, all I had, as is often the case with children, was the instinctive self-defence mechanism of embarrassment. I had a terrible time of it, and used to say to him “granddad, I’m embarrassed.” And his reply always comes to mind when I think of tourism. The reply was: “I don’t know why you should feel embarrassed – you’re never going to see them again”.

© Library of Catalonia. Gaziel Collection

The journalist Agustí Calvet, Gaziel, reflected on tourism many times in his work. In the image, Gaziel at the port of Sant Feliu de Guíxols, his birthplace, in August 1963.

In other words: pure exploitation. If you’re lucky enough to have some birds flying over your land, you get out the shotgun and shoot. A basic business notion, yet unthinkable in a bakery, a factory or a garage. Don’t worry about the customers, you’ll never see them again. I’m not saying that’s how tourism is, naturally. All I mean is that my grandfather would not have had this irresponsible idea in any other type of business. And the problem is that this exploitation doesn’t only apply to tourists, but to everything that revolves around tourism. The culture of exploitation does not only apply to tourism, of course, and a country’s level of development can be assessed by its degree of exploitation – we’ve seen it with the housing bubble and we’ve seen it in terms of political corruption. In cultural terms, were talking about anti-tradition.

Just like with pork, nothing goes to waste when it comes to tourism: you can make use of everything the tourist and the tourist site have to offer. There’s no need to create anything, just take what’s already there. You’ve got a beach? Then sand and sun. Wine? Enotourism. Some sort of monument? “Cultural” tourism. But the day will come when tourists open their eyes to the self-deception, to the massive ride they’re being taken for under the pretences of the virtues of travel. Homer would turn in his grave!

In times of economic crisis however, what can you do about it? In times of crisis you rent out a room in your house. In Barcelona this has reached dramatic levels with the problem of tourist apartments, but we are also familiar with this issue on the Costa Brava. I too occasionally had to give up my room so that tourists could spend the night there. Marina Garcés talks about the blackmail this involves, and she is totally correct, but is there anything that can’t be called “blackmail”? As with everything, it’s a question of to what extent. Reflecting on tourism is not an easy thing to do as so many of our livelihoods depend on it, and it is a question that currently touches on the very essence of our country. Tourism puts food on our tables and we are therefore highly conditioned by it; it reflects directly on us. We should have a first-class tourism observatory, cutting-edge, fully independent and with a regulatory role, to keep the matter permanently open to public debate.

At the last FITUR tourism trade fair, Mariano Rajoy called the tourism industry the “flag ship” of the Spanish economy, because that is what it is. Whether or not this is something to be proud of is another matter. There’s something slightly humiliating about running after people like a bazaar hawker: ‘look what I’ve got! Who wants it? If you don’t want beaches, I’ve got mountains! And if not, I’ve got…’ But we’re in an economic crisis, it’s common sense.

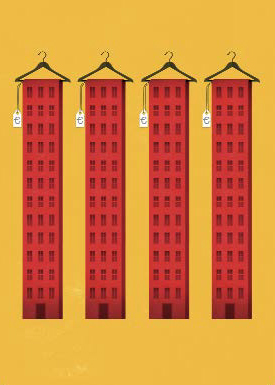

In that same edition of FITUR, the Catalan Government invested more money than ever before in a tourism campaign: 3.8 million euros. The campaign was run under the slogan of “Catalonia is your home”. The singer-songwriter Sisa himself has assigned the rights of Qualsevol nit pot sortir el sol, a song that has become such an intimate part of our culture, so a version can be made for the adverts.

“Catalonia is your home”. Here lies the problem. My home is your home. Is it not pertinent to ask ourselves what gives the authors of the new tourist campaign the right to so willingly give away the region to outsiders? What authorises them to offer my home to someone else? Isn’t Catalonia mine, then? Have they thrown me out? Was it ever mine? Have they sold it? Do I not have a say in the matter?

This is another anecdote, but it explains more than grand ideas. If I believe that someone else’s home is my own, I can do what I want there, I’ll be allowed to exploit it however I like. Coming soon, a competition to see who’s got their wits about them, who can exploit who best.