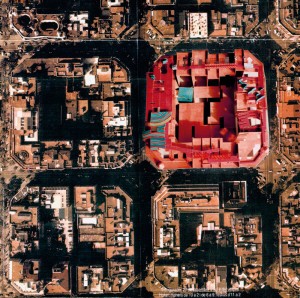

Photomontage of Plaça Catalunya with the light, transparent library designed by Pau Bajet on the site of El Corte Inglés.

The graduation projects of the School of Architecture of Barcelona (Escola d’Arquitectura de Barcelona – ETSAB) are a good database on the way architects see the city. Facilities, town-planning developments, infrastructures, solutions to problems, bold ideas… all of this has been tackled in countless proposals. Two hundred and sixty projects were chosen, the best of the last 50 years of the ETSAB’s life, to make up the exhibition Escola-Ciutat, cinc dècades de projectes finals de carrera d’arquitectura a Barcelona (College-City, five decades of architecture graduation projects in Barcelona), which was on show for one week at the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya (MNAC) last October and which will be given a second lease of life at the ETSAB building.

The curators are Roger Such and Ariadna Perich, Associate Professors and Assistant Directors in the Department of Culture of the ETSAB. The selected projects since 1977 also provide a rough picture of the fate of the real city and the one these students imagined when they were preparing to leave university. The projects focus their attention on a range of aspects: the Ciutat Vella district accounts for a lot of proposals during the early years of democracy, while the 90s illustrate the tendency in the city to extend and diversify the network of facilities. Other interesting lines of argument are concerned with developing and dignifying town-planning, the promotion of the 22@ district, the design of the large area between Plaça de les Glòries Catalanes and the Fòrum and infrastructures and natural spaces.

Here is a small sample of the graduation projects as seen by their authors, practising architects who have agreed to take part in the experiment of returning to the past and contextualising it in the present.

Eduard Gascón approached his graduation project in 1984 in the framework of the study programme ‘Del Liceu al Seminari’ (From the Liceu to the Seminary), held at the ETSAB and based on the municipal town-planning project of the same name launched a few years before with the object of bringing new life to the Raval district and connecting it with the Eixample. He did the work with Francesc Mitjans as his main tutor. Today the architect of the future Nou Palau Blaugrana, as well as many other projects, he remembers that his project caused a bit of a stir. ‘I started from the idea of recovering Plaça de la Boqueria for the city, as it was a space not unlike Plaça Reial before the market structure was built in 1840. I was convinced it was better to recover a quality architectural space with a perimeter of Neoclassical columns which already formed a public square by themselves’, he explains. In this way, the Rambla would have had a direct connection with an open community space, like a public square. ‘I placed the market over the Gardunya car park, which already existed and in which I set aside one underground level for loading and unloading. I followed a historicist criterion and designed inclined roofs with a metal structure. It would be on two levels: on the ground floor, the market for fresh produce, and on the first floor, a large supermarket’, he goes on.

A few decades after Gascón’s proposal, there was something of a debate about the possibility of moving the Boqueria to Plaça de la Gardunya. The funny thing about it is that today, 33 years after the graduation project, La Gardunya is in the process of completing its new layout. After all this time, Gascón still sticks to his idea, ‘I still think reclaiming La Boqueria as a public square was a good idea’.

The original idea for this 1992 project by Eva Prats had its starting point on a roof terrace in Ciutat Vella that some of the architect’s friends had turned into a communal space. ‘I thought of developing the same sort of thing but on a much bigger scale, a whole city block of the Eixample, precisely because of its compact, repeated, rigid structure’, says Prats. She looked at one particular block, the one bounded by Carrer Ausiàs March, Carrer Ali Bei, Carrer Girona and Carrer Bailèn. It was a completely built-up space, both along the perimeter and in the interior, and the layout of the buildings, of similar heights, let her design a continuum of structures — including a bridge! — connecting the roof terraces, which were ‘closed spaces that had been abandoned following the remove of the old water tanks’.

Prats, whose tutor was Enric Miralles, started by calculating the structures to place in each of the spaces and the walkways that would connect the buildings. She planned a large terrace that would house a practical area for a gardening school, an area for aquatic plants and another for pruning lessons, a greenhouse, an area with different types of lawn and another for climbing plants. All of this in minimal containers without much earth and with a watering system based on water tanks.

Another indispensable aspect of the project was to create spaces for the residents. ‘All the people living in flats in the block would enjoy the whole of it’, the architect explains. ‘The idea was that they would be able to use it to hold parties or meals, things you can’t do in a home because of the limited room’. Prats’s idea didn’t fall on barren ground. Some years later that project has roused interest and the mock-ups she did in 1992 have been in demand for exhibitions. Even Barcelona City Council – both during the current term of office and under Xavier Trias – has taken a look at the idea, though without going so far as to develop it. In the course of her professional work, the architect, along with her partner, Ricardo Flores – winner of this year’s Ciutat de Barcelona award for the refurbishing of the Sala Becket –, has taken the approach of favouring communal spaces and looking for solutions with garden elements. ‘To create a garden on a roof terrace, the one thing that’s really essential is that the residents’ association should want to do it’, she claims, 25 years later.

David Martínez García, who was born in Santa Coloma de Gramanet in 1973, looked at this inhospitable bridge at the start of the 21st century and thought of turning it into an urban promenade that would act as a link, drawing together the town’s main street and the avenue that connects it to Avinguda Meridiana, according to the project he conceived in 2001. ‘I imagined the bridge as a symbol of recovering run-down urban space for people, in this case in the context of the recovery of the Besòs river, which we all remembered as an open sewer. I took classic Italian bridges as my model, and more specifically, the Ponte Vecchio in Florence. You might say it was an architectural project with a marked town-planning component’, says Martínez.

In fact, this has been his main professional practice since then. He was responsible for town-planning services for Badalona Town Council until 2011, when he joined the same department in the Barcelona Council, where he still is with the mission of relaunching the 22@ district. ‘The programme I developed had three parts to it: first of all, it opened up an area of commercial spaces, shops; secondly, it proposed partly covering the ring road with a system of prefabricated pieces without pillars, in which commercial activity could also take place, and thirdly, it included an interpretation centre for the Besòs river explaining its history. The project also included a structure providing access to the riverbank’, he remembers. The idea behind the whole project was to humanise an area that had become a mere connecting road. ‘On the other hand, in all these years the Pont Vell has hardly received any ambitious treatment and only a bit more room for pedestrians has been gained’, concludes David Martínez.

Biblioteca Nacional de Catalunya (National Library of Catalonia)

Rather than national or provincial, the 2013 project by Pau Bajet was for a central library in the very centre of Barcelona, Plaça de Catalunya, right in the immense urban plot occupied by El Corte Inglés. Eduard Bru, his tutor and a professor at the ETSAB, suggested this programme to him with a groundbreaking idea: ‘Why not put a cultural catalyst in the centre of the city confronting capitalist power as represented by the rest of the urban activity?’ This reflection wasn’t unlike the proposals to locate the planned Biblioteca Provincial in the Bank of Spain building in the same city square. ‘It consisted of a large building of almost 30,000 square metres based on the Renaissance concept of the library as a large space representing knowledge. For my part, I added the wish to make it transgressive. The structure was of polished concrete, as close as possible to stone, developed with prefabricated elements and with dimensions on a human scale’, he explains.

In contrast to El Corte Inglés and its opaque façade, Bajet proposed enclosing the library on the outside with a sort of latticework façade that would allow a view of the interior from the square, though not from Passeig de Gràcia or Carrer de Fontanella. The visitor would find a large atrium and a system of ramps with the walls lined with shelves and books. ‘Leaving aside the traditional appearance of the classic libraries with compartments and floors, I designed a single space that could be traversed continuously, without floors. From the moment you went in, you could make out the ceiling. Even so, more sheltered areas were generated: the overall monumentality of the construction contrasted with the more domestic nature of the other, smaller areas’.

No-one would argue with the statement that Plaça de Catalunya is the result of different operations over the course of time that have given it a fairly disjointed and questionable overall appearance. Some years after that proposal, Bajet, who after working in England with David Chipperfield opened his own office in Barcelona, feels that his project helped to improve this untidy group of buildings currently making up Plaça de Catalunya.