Linguistic sustainability would recognise the rise of plurilingualism and intercommunication, while also reclaiming the conditions required to guarantee the continuity and development of various linguistic groups.

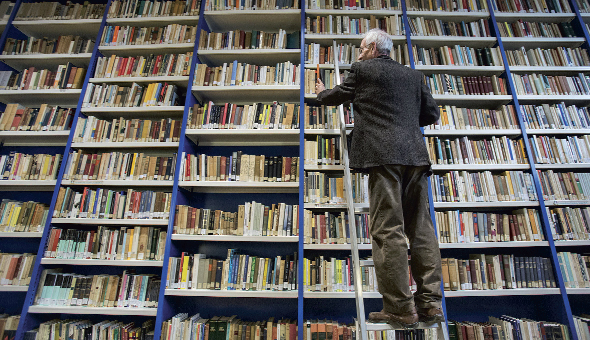

The library at the Italian Institute of Culture in Barcelona. Italians make up the most numerous group among foreigners in Barcelona, and are also one of the oldest, most firmly rooted and most influential groups.

Photo: Pere Virgili.

The 21st century has led us to polylingual metropolises where populations that have already been bilingualized – being integrated into states in which another language is predominant – live day to day alongside many people with different first languages, who come from the rest of the same national territory and/or places all over the world. In more developed societies, there is also a growing trend towards the domination and use of major international languages, due to the fact that many companies and organisations participate in continental or global techno-economic networks. This huge increase in linguistic contacts represents a very significant change in the regional socio-cultural ecosystems in which different human groups have traditionally developed their languages. If we fail to learn how to manage these new situations properly, then sociolinguistic trends could have future effects that are not exactly positive for human language diversity.

The need for mutual understanding in urban spaces and the skills that are most available to individuals tend to lead to a rise in the use of the languages that are the most widespread internationally. In the case of societies where these widespread languages are already their own, the mass arrival of new populations may not affect them too much. This situation, however, may be different in the case of medium-sized language communities, which are already characterised by their own status as largely bi- or plurilingual communities. A significant influx of people from other places can seriously increase the use of the national or international language that predominates in that place, at the expense of the local language.

These kinds of phenomena are clearly visible in the case of Catalan, where the local population generally has knowledge of Spanish, and this is the language for integration that more recent immigrant populations normally develop spontaneously (if they do not already have it). The perpetuation of these inter-group habits cannot be ruled out even in successive generations – despite the fact that their children may have been born in Catalonia and educated there – because of the forces of the sociolinguistic habits established in metropolitan areas especially.

How can we manage this series of new contacts from a standpoint of respect for human linguistic diversity, while giving the local language, Catalan, the inter-group communicative role that will ensure its future? Maybe we can find clues in the principles the philosophy of sustainability has developed to maintain biodiversity and balanced socioeconomic progress. In doing so we could also seek the necessary fraternity and solidarity that should exist between members of a species that is culturally diverse, yet one and the same.

To paraphrase Ramon Folch in an interview about sustainability in general, we could say that “linguistic sustainability” is a process to gradually transform the current model of linguistic organisation with the aim of preventing the collective bi- or plurilingualization of human beings from leading necessarily to the abandonment of the different cultural groups’ own languages. Linguistic sustainability, therefore, would recognise the often inescapable rise in plurilingualism and intercommunication, while at the same time reclaiming the conditions required for the continuity and full development of human linguistic groups.

From this point of view, sustainable linguistic contact would be contact that does not generate linguistic exposure or use in a language that is not the group’s, to an extent or pressure that is so high as to make the continuity of the indigenous languages of the human groups impossible. We could thus say that the sustainable nature of mass bilingualization could be determined by comparing the degree of appreciation and functions of the language that is not the group’s own with that of the language that is. If this degree is lower in terms of the other language, then mass contact and bilingualization can be sustainable. If it is higher, then billingualization will most likely not be sustainable and the group’s own language will begin to be abandoned and will disappear in a few decades.

Taking action with regard to the abandonment of groups’ languages by their bi- or plurilingualized speakers means, in particular, building contexts in which they will not develop negative attitudes towards their original language, and where they will be able to have valuable and worthy uses for their language and their group. In cases in which the demo-sociolinguistic conditions mean that the speakers begin to stop using their language, for practical reasons, in a spontaneous and self-organised way (often unconsciously), it would be necessary to make them aware of their developmentally self-destructive behaviour, and to promote the deserving appreciation of their own cultural attributes.

It is obvious that public authorities play a very important role in this pursuit of linguistic sustainability, as they have to transmit positive discourses; provide an example of the most relevant rules of usage; regulate the public administration, education and services from a linguistic standpoint; and also guide the communications of non-official organisations towards this objective. The principle of linguistic subsidiarity – “anything a local language can do should not be done by a more global one” – could be, among other things, the basis for an equitable distribution of functions, which would ensure the local language in the society’s general communication, at the same time as the use of other languages in the functions that each group or person deems appropriate.

Article molt interessant. Jo diria que potser la frase clau és “El caràcter sostenible d’una bilingüització massiva vindria donat per la comparació entre el grau de valoració i de funcions de la llengua no pròpia i el de la llengua pròpia del grup”. I, a la frase següent (“Si el primer és menor, el contacte massiu i la bilingüització pot ser sostenible. Si és major, la bilingüització probablement no ho serà […]”), hi afegiria un matís: “[…] Si és IGUAL o major la bilingüització probablement no ho serà [de sostenible] […]”. Vet aquí un principi teòric general que ens hauria d’orientar en tot el debat, ara revifat, sobre el tema del futur estatus de català a Catalunya (si és que, finalment, aquest tema acaba depenent només dels catalans).

I trobo que el fet que la pretensió que la bilingüització d’una comunitat lingüística hagi de ser OBLIGATÒRIA (és a dir, afecti tot el grup), i a més amb exigència de coneixement (gairebé) IGUAL que el d’un nadiu, té relació amb el fet que el “grau de valoració i de funcions de la llengua no pròpia” sigui igual o superior al de la llengua pròpia; és a dir, robo que aquesta pretensió té relació amb la no sostenibilitat d’aquesta bilingüització.

Finalment, contra el darwinisme lingüístic, molt d’acord amb el darrer paràgraf, que parla del paper dels poders públics com a agents que intervenen i legitimen “aquest assoliment de la sostenibilitat lingüística”.