Barcelona’s municipal government is working on various ways to provide citizens with greater access to information on public affairs as the basis for boosting public involvement in their management. The establishment of the Office for Transparency and Good Practices, the Ethical mailbox and the Transparency web portal are some of the actions that have been taken for that purpose.

A code of conduct is also being drafted for elected officials and high-level municipal staff. In addition, work has been underway since the summer to amend the regulatory standards governing civic involvement in public affairs. The regulations being brought into effect go beyond what is required by the law on transparency, access to public information and good governance, which was passed by the Catalan Parliament in 2014.

In December 2014, the Catalan Parliament ratified Law 19/2014 on Transparency, Access to Public Information and Good Governance with CiU, ERC, PSC and PP all voting in favour. Iniciativa and Ciutadans abstained and CUP voted against. In June 2015, during her inaugural address, Barcelona’s Mayor Ada Colau spoke of a City Council in which “people feel that they have an important role” and she urged residents to get involved in designing and assessing public policies and making them more transparent: “We want a new City Council with glass walls, because if the public does not have information, democracy is not possible”, she added. The Law on transparency only came into force in Catalan town councils a year ago, in January 2016.

But the council’s intention of giving the public access to data that is of public interest goes back to 2010, when former Mayor Jordi Hereu’s team put forward the proposal for what would later become the council’s open data service. Since then, the internet portal that provides the open data service has gathered 330 datasets, according to Chief Technology and Digital Innovation Officer of the City Council, Francesca Bria.

Although the volume of data is starting to become quite significant, the Association of Archivists of Catalonia is calling for more coordination when it comes to establishing a shared methodology for classifying, integrating and standardising documentation, as archivists have been carrying out this task for some time and have found that the resources and information available on the City Council website and in the municipal archive are sometimes duplicated.

In addition, the format of the data has to be reusable. In other words, it has to be in the form of spreadsheets and not PDF documents, to allow analysis and comparison with other data and to be more representative, says Karma Peiró, a journalist specialising in information technology: “We want the original archives, not the Administration’s interpretation of them”, she points out.

Inauguration of the Office for Transparency and Good Practices, November 2015. From left to right, director Joan Llinares, deputy mayor Jaume Asens and two members of the Office’s advisory board: Simona Levi, from Xnet, and journalist David Fernàndez, former member of the Popular Unity Candidacy party (CUP), who headed up the parliamentary commission of inquiry into alleged wrongdoing by former Catalan President, Jordi Pujol (known as the Caso Pujol).

Photo: Barcelona City Council

Office for Transparency and Good Practice

In November 2015, the city council launched the Office for Transparency and Good Practice (OTBP), which, through its digital tool, the transparency web portal, is to be the first guarantee of this government with glass walls that Colau announced in her inauguration speech.

The office reports to the Department of Public Rights, Participation and Transparency, which is led by Jaume Asens: “Transparency makes us weaker as a government, because the opposition knows where we are at all times, who we’re meeting, what we’re doing; and this information is very valuable to them because they can use it to get ahead of the game. But at the same time, it makes us stronger”, says Asens.

The person at the helm of the OTBP is Joan Llinares, Manager of Council Resources. As someone with no small experience in corruption scandals, Llinares was the person who took over the management of the Palau de la Música after Fèlix Millet was found to have defrauded the institution: “The role of the Office, together with the council’s legal services, is to develop the regulations that will be rolled out to guarantee the principles of transparency and good practice”, he says.

These regulations, which go beyond the requirements of Law 19/2014, according to Llinares, provide for the creation of an Advisory Committee on Transparency to support and audit the Office. The committee is made up of twelve people, most of them from community groups and civil society, who receive zero remuneration for their work. The list includes people like Itziar Gonzàlez, David Fernàndez, Josep Ramoneda, Francesc Torralba, Miguel Ángel Mayo of Geshta (the Trade Union for Inland Revenue Staff), and Simona Levi.

In fact, the group of which the digital activist Simona Levi is a member – XNET, which acted as the public complainant in the Bankia trial and is behind the 15MpaRato Citizens Against Corruption initiative – has been charged with implementing the ethical mailbox service.

The ethical mailbox is an open mechanism that allows members of the public to denounce any illegal behaviour by governments or any other official organisation, with guaranteed anonymity and protection, thanks to the free TOR encryption software: “It’s been a technological task and it involved changing the technical protocol of the City Council’s entire I.T architecture, but we’ve also had to generate understanding of this new way of doing things, which is more of a cultural change”, says Simona Levi. Other traceability protocols have been incorporated that allow complainants to track the progress of their complaint, thus ensuring feedback from the authorities, and allowing people also to complain if they feel their case is not being properly handled: “We are trying to get people to take control of their own complaint, to take ownership of it”, explains Levi. “There have to be ways of preventing participation from being a painful process. Public vigilance must not take over your life.”

At the Office for Transparency, they admit that they have taken too long to launch the services and apply the laws. The mailbox was meant to be ready by January 2016, after the hacker-proofing and external filter resistance testing phase was complete in December. According to the Director of the OTBP, Joan Llinares, organisations and individuals were asked to break through the security barriers to find out if they really were impenetrable.

A general code of conduct

All we know about the ethical code of conduct is the blueprint that was presented in March. The Council has been seeking the consensus of political parties and civil society groups to be able to push ahead with it: “It’s like a constitution,” claims the Fourth Deputy Mayor, Jaume Asens. “Everyone has to abide by it, so we want everyone to give it the green light.” The official process began in December and will culminate in a municipal plenary in February. As such, by March, the City Council will already have its two main instruments for transparency and good practices in place.

The code will serve to prevent and report conflicts of interests, incompatibilities, unjustifiable expenses and the acceptance of gifts worth more than €50: “Unlike other codes of ethics that are only declarations of principles and therefore not much more than lip service, ours goes above and beyond ethics,” claims Jaume Asens. “This is a true code of conduct that, if it gets the compliance we predict, will have very clear positive effects.”

The code is aimed at all elected positions, executive staff at the City Hall, the organs of government of all associated Council entities and even the temporary staff working at the Council and its associated entities who hold positions of trust or advisory roles.

Political malpractice has not always been punished; quite the contrary. We should recall the €3,000 fine imposed by the Supreme Court on the NGO Access Info Europe in 2012 for having asked the executive what measures Spain had taken to fight corruption. After the Partido Popular government set up the transparency portal for the whole of Spain, the Director of the NGO, Helen Darbishire, was critical: “For a country to be transparent, there has to be a cultural shift.”

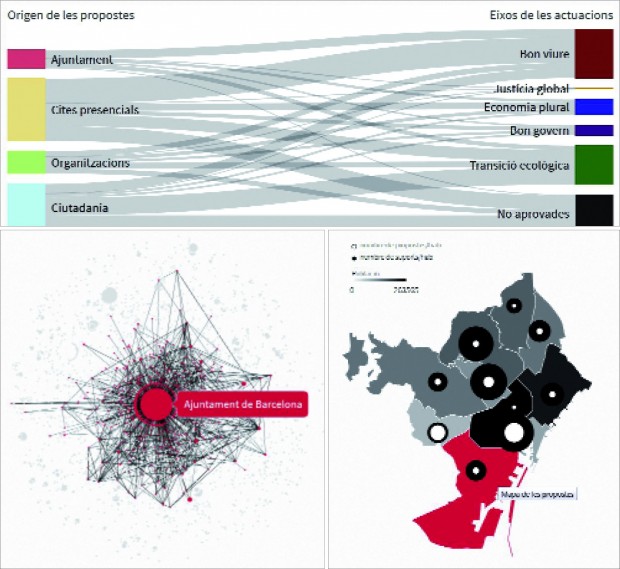

Interactive images from the Let’s Decide Barcelona (decidim.barcelona ) website, which provides information on the different aspects of the participatory process that were implemented in preparation for the Municipal Action Plan 2016-2019. The first depicts the distribution of proposals according to origin, and which ones were incorporated into the strategic thrusts of the plan; the image below, on the left, provides information about the entities and citizens who actively participated in the process; the image on the right represents the number of proposals per inhabitant that were registered in each district, and the volume of support that they received.

Smart city versus technological sovereignty

According to Francesca Bria, Chief Technology and Digital Innovation Officer, today’s digital economy is based on data. That is why the majority of data is concentrated in the hands of very few companies that tend to be technology firms, banks or insurance companies: “We are living in the time of the wild west of the digital economy: data are the oil of the 21st century”, she warns.

Bria accepts that there is still a long way to go and she points out that the Council is in touch with other local authorities in cities such as London, New York and Helsinki, with which to share information in this area. “We need to go beyond static data that relate to the past, and monitor the city’s dynamic data, in other words, the data that speak to us in real time about mobility or pollution levels, for example,” explains Bria. These data are useful for the City Council and they must be accessible to it so that it can improve its services”.

In October, the City Council presented its Barcelona Digital City Plan 2017-2020. The Transition to Technological Sovereignty, which has a budget of 65.6 million euros. This plan sets out to guide the Council’s digital transformation by laying down the standards for open code and free programming software. “We have included a clause by which all the information in contracts with external providers and the resulting activities (cleaning, lighting, the bicing bike-share system, etc.) must be made public, because they relate to public facilities”, explains Bria.

She maintains that we need to diversify the digital economy so that it is not “in the hands of some companies, as happened with the idea of the smart city, which put technology before anything else simply to make money”. For Bria, the answer lies in putting all the Council’s digital efforts into hiring Catalan SMEs to provide services. “To do this, our digital plan allocates ten million euros to innovative public procurement, and this means adapting the Council’s relationships with providers to include SMEs”, she explains.

Making data more than just a juicy business resource for the private sector and ensuring that it provides returns for the public purse would be the first step in achieving technological sovereignty. But there is no sovereignty without social empowerment. Many members of the public are unaware about what is done with their personal data. “The digital economy often violates our basic rights to privacy,” claims Bria. “We have to intervene here, to ensure that members of the public really are the sole owners of their data”. In addition, Bria talks about how the Council needs to exercise its public leadership to set out the priorities for putting technology at the service of the public.

The participation process Decidim Barcelona (Deciding Barcelona)

The first example that Francesca Bria gives when she’s asked how the public leadership of council policies should be developed through transparency and technology is the participation process that helped to elaborate the Municipal Action Plan (PAM) 2016-2019, which began in October 2015, with the name of Decidim Barcelona. The Head of Projects at Barcelona’s Residents Federation (FAVB), Joan Maria Soler, gives a positive evaluation of the work done: “There has a been a clear desire on the part of the Council to implement participation processes, with an intensity that had not been seen before.”

Over 15,000 people attended the workshops and preparatory meetings, but the bulk of the participation happened through the Decidim Barcelona internet portal, which has 24,000 registered users: “Never before has there been a municipal action plan with real public participation”, points out Bria. But Joan Maria Soler sees the FAVB’s participation experience a little differently, as “not very successful in quantitative terms” given that only 2.4% of the city’s population took part.

10,860 proposals were collected from individuals, organisations and associations, to be incorporated into the Plan, of which 8,142 were finally included. According to Soler, some of the proposals in the Plan are having limited returns: “There was a very high sense of expectation (the process went on for a long time and it was intense) and in some specific cases, there was frustration. Proposals that received a lot of votes were then interpreted too weakly, or given a less radical spin.” Soler gives the example of the project to cover the Ronda de Dalt ring road, which was the proposal that got the most votes regarding the ring road issue and which, according to Soler, was dealt with in a very lightweight manner by the Council, with deadlines that are too long. When asked about this, Joan Llinares accepts that the results have not been as hoped, but assures that it is because of budget priorities and is nothing to do with the aim of covering the road, which remains intact.

The Fort Pienc ward council met on 14 December 2016 to discuss the launch of a participatory budgeting pilot project in Eixample. Both this district and Gràcia are the first areas in which the participatory process is being implemented, on a trial basis, as a means of enabling citizens to make proposals and take decisions regarding the use of municipal funds in various areas.

Photo: Albert Armengol

There is no magic wand that can strengthen participation, but Soler does refer to the self-management of public spaces: “We can do wonders when it comes to participation, but if people don’t meet in their neighbourhood, there is no way we can achieve it,” he says. “Facilities, day centres and community centres should be self-managed as much as possible: people need to feel that they are an active part of these spaces, not just customers or users”.

Since the summer, there has been a process to review the laws governing public participation in the city. Joan Maria Soler explains that the FAVB forms part of the committee that instigated this process and says that, while it is too early to draw conclusions, the Federation will put forward its own long-standing demands to the discussions on public participation: “District councillors chosen directly by the public, the ability to develop public legislative initiatives, having binding consultations with residents and decentralising the city government. The districts must have real decision-making power on many issues that are currently closed to them, such as the area of urban planning”, maintains Soler. The Director of the Office for Transparency, Joan Llinares, also accepts that it is still very early days but he does point out that participation “should be based on administrators’ commitment to be accountable to the public”.

A report entitled Transparència, accés a la informació pública i bon govern (Transparency, Access to Public Information and Good Governance) produced by the Catalan ombudsman, the Síndic de Greuges, in July 2016 (Law 19/2014 gives the ombudsman the authority to assess its compliance) says that Barcelona is Catalonia’s most transparent city of over 50,000 inhabitants, when it comes to active council communication or the public’s right to access public information. The UAB’s Laboratory on Journalism and Communication for a Plural Public also conducts a yearly assessment of the transparency of all Catalan town councils. In the 2016 survey, Barcelona City Council meets all 52 requirements.

One of the clearest examples of the winds of change in the city government is the Transparency web portal developed by Civio, where one can look up the council budgets from 2013 to the budget proposals for 2017, in an open format with interactive viewing options. Or there’s the opportunity to download a spreadsheet of all the invoices processed in the City Council in 2015.

One may ask oneself what real power the people would have if all town councils made this information accessible to their residents and if people were interested. One last piece of data: the private company that sent the Council the biggest bill last year was the building firm Fomento de Construcciones y Contratas (FCC), for €116,155,886.43. And it’s the Office for Transparency and Good Practice that is responsible for auditing FCC’s alleged €800,000 fraud in the Council’s cleaning service.