For 112 years and 364 days, Barcelona’s Model prison took in those whom the social and legal ideals of different regimes had cut off from the collective, from that which is deemed acceptable, from the public sphere. Society, either by submission or inaction, accepts a contract: the state protects us from crime in return for the right firstly to decide what counts as crime and secondly to exercise a legitimate use of force and confinement.

Photo: Arianna Giménez

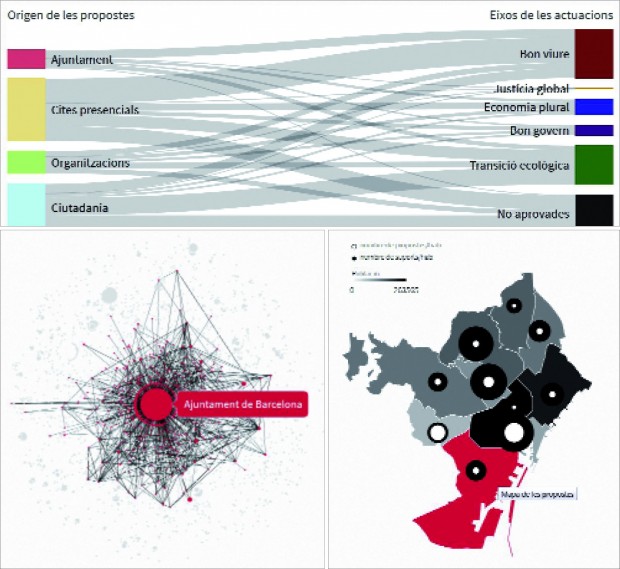

Until 10 January 2017, when the Catalan Government and the City Council signed the agreement to close the prison, nobody had believed this closure would actually happen, despite promises from Barcelona’s last three mayors. The Model prison has since been emptied of its prisoners – the last group left in a Catalan police force armoured van on 8 June. Now, for the residents in this part of the city (Nova Esquerra de l’Eixample), the two city blocks the premises encompass represent both an opportunity and a danger, as they watch to see what sort of restoration will be given to this large chunk of their neighbourhood, following four decades of calls for the prison’s closure in order to make way for amenities, green spaces and schools.

Used for pre-trial detentions – for prisoners without guilty verdicts – the Model prison is among the public institutions best equipped to tell us how the city of Barcelona experienced the 20th century. Its detainees have included people who stole (be it to put food on the table, to feed their addictions or just to satisfy their greed), people who dealt drugs (mostly people dealing in small amounts) and people who were at odds with the regime as regards their ideas and/or the political beliefs they expressed.

Francesc Ferrer i Guàrdia – educationalist and founder of the Escuela Moderna – was arrested in Barcelona in August 1909, accused of being one of the instigators of the riots and confrontations commonly known as the Tragic Week. On Saturday 9 October he was tried without due process by court martial in the auditorium of the Model prison, and condemned to death for military rebellion. When facing the firing squad in the Montjuïc cemetery on the morning of 13 October, standing rather than kneeling he shouted his final words “Long live the Escuela Moderna!”

Bulldozers preparing the ground for the portapacks for the Eixample I school last June on the part of the building demolished in 2015.

Photo: Arianna Giménez

The Eixample I school was inaugurated within the grounds of the old prison last September, coinciding with the start of the academic year. Locals in the Nova Esquerra de l’Eixample neighbourhood, having spent decades calling for the City Council and the Catalan Government to close the prison and open schools, amenities and green spaces in its place, now bring their children to be taught where the founder of the Escuela Moderna was condemned to death.

Jaume Asens is the fourth deputy to the mayoress of Barcelona and heads the council’s Citizens’ Rights, Participation and Transparency department. He invokes the words of Victor Hugo, that “he who opens a school door, closes a prison”. The doors of the Eixample I school are not as heavy as those of the Model prison were. Indeed, they are quite a lot lighter, as are the classrooms as a whole, consisting of huts installed in the part of the prison that was taken down under former mayor Xavier Trias in March 2015, on the corner formed by the streets Entença and Roselló. Diggers moved in at the start of July, and after they were done, a mural was left visible on the wall of the prison: “From the Model prison (1904-2017?) to a model for transformation, culture, cohesion, remembrance and neighbourhoods”.

For the Esquerra de l’Eixample Neighbourhood Association, the 2009 Master Plan for the Transformation of the Model Prison, which was designed in collaboration with neighbours and local businesses, remains valid. It envisages the creation of a primary school, a nursery school, a residence and day centre for senior citizens, an activity centre for young people, a sports centre, underground parking, a healthcare centre, a memorial to democracy and a green space – facilities urgently needed by a neighbourhood with almost nothing in the way of parks or schools.

Up until the opening of the Model prison, the city’s largest prison was one located on Carrer Reina Amàlia, in what is now Plaça de Josep Maria Folch i Torres in the Raval neighbourhood. It was a building that historically had been a convent for Paulist nuns, but was used as a prison as of 1839. In conditions of dire overcrowding and unsegregated yards and corridors, there was a mix of women, youths, children, elderly people, men who had been condemned, people awaiting trial, people who were ill and others about to become ill. The Model prison’s first inmates were the men from the Reina Amàlia prison, which continued to function as a women’s prison in dreadfully insanitary conditions up until the Spanish Civil War.

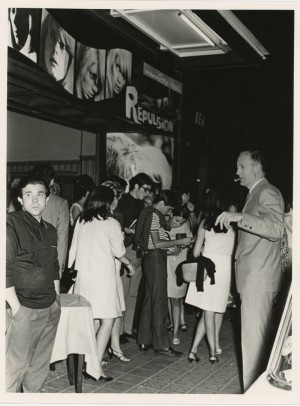

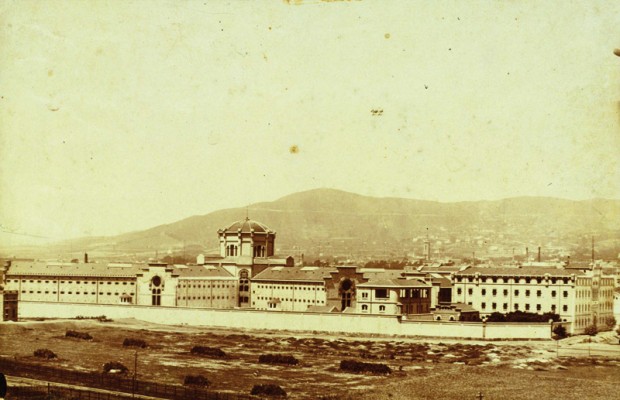

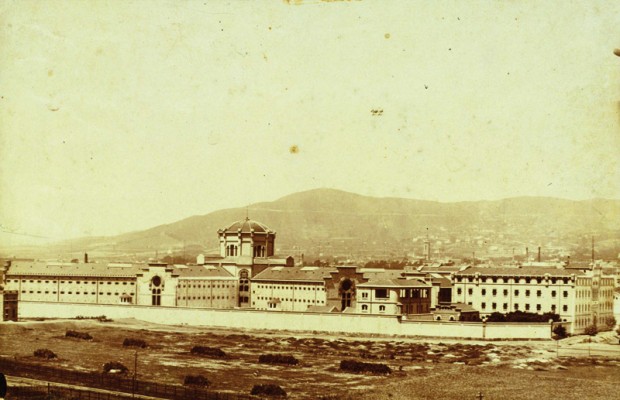

The Model Prison, surrounded by fields and empty plots in June 1904, when it was opened, though still unfinished.

Photo: AFB

However, the idea was that conditions in the new prison would be quite different. The Model prison was thus named because it was to be exemplary for its functional excellence. Building works based on the designs of architects Salvador Vinyals i Sabaté and Josep Domènech i Estapà began in 1887, the year before the Universal Exposition, but the prison was not inaugurated until 9 June 1904, and even then it was still unfinished. It was then surrounded by building plots, cabins and smallholdings, some distance from the Eixample district that at that time went no further than Carrer Balmes and would take another thirty years to reach Sants, making the Model an urban prison, the Barcelona jail.

It was the first Catalan prison to use the cell system, i.e. a space for each prisoner to sleep in individually. Furthermore, the Model prison was designed as a panopticon structure, based on the architectural principles of Jeremy Bentham. This meant that the central watch point gave a comprehensive view throughout all six of the galleries, which extended like the spokes of a wheel from the circular ‘hub’ building.

In comparison with overcrowded jails with shared cells, galley slavery or earlier customs of torture and public suffering, Barcelona’s new Model prison would not have seemed so bad. But the improvements were not arbitrary. The constant surveillance, the isolation, the discipline regarding work, meals and timetables, the control over prisoners’ bodies by the staff and the punishment quantified in terms of years sought not only to mould prisoners physically, but also to change them as individuals. As Michel Foucault explains in Discipline and Punish, “It [the prison] must be the most powerful machinery for imposing a new form on the perverted individual; its mode of action is the constraint of a total education”.

For the first time, Barcelona’s prisoners felt the gaze of constant surveillance resting upon them, while also being alone in their cells, unable to talk to anyone – unless they shouted – for hours on end, in a society that was still used to almost continuous verbal communication.

During the initial years the prisoners’ living conditions were not bad, indeed in many cases they were better than they would have expected in their lives on the outside. The Model prison was designed to house around 850 prisoners. The cells were no more than 9 square metres and were for one person, the prison meals provided enough sustenance for the minimal exertion demanded of prisoners in their isolated state, and illness was relatively infrequent thanks to vaccination campaigns and the work of the infirmary. However, this was a situation that would not last for long.

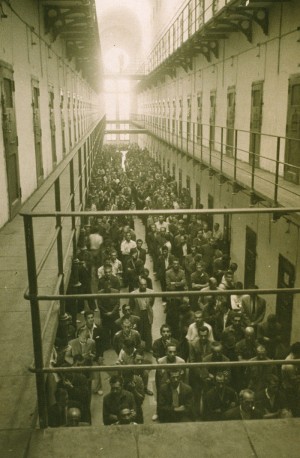

Prisoners at the mass for the La Mercè festivities in 1946.

Photo: Pérez de Rozas / AFB

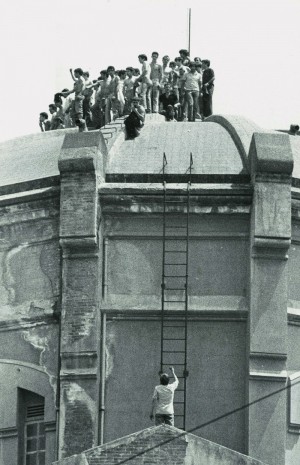

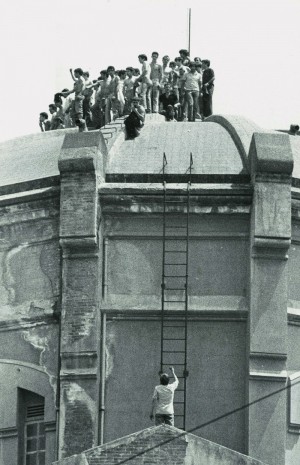

A group of protestors demanding an amnesty, on the roof of the prison on 19 July 1977.

Photo: Pérez de Rozas / AFB

Political and social repression

As the city grew up around it, the Model prison received fewer and fewer resources to properly look after the inmates, despite being filled more and more densely with an increasingly diverse population. Not many years after it was opened, the regular prisoners began to see alongside them political prisoners – those seen as capable of destabilising the regimes of the time.

The Model prison thus became a symbol of repression and the people of the city began to associate it with government arrests – which required no more than a police order to incarcerate the person targeted – or with the so-called ‘ley de fugas’ (escapee law), an abhorrent trap where a prisoner would be released and then shot in the back immediately upon exiting the prison, under the allegation they were escaping – you can picture the scene at the main gate. After its initial years of being popularly referred to as ‘the tower’ or ‘the Carrer Entença hotel’, within a decade the prison had become one of the darkest symbols of repression, on a par with Montjuïc Castle and Camp de la Bota from the Franco era.

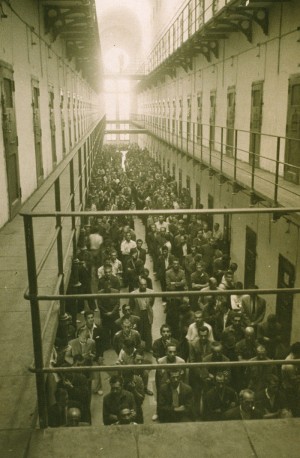

When Franco’s troops triumphantly entered Barcelona, towards the end of January 1939, the prison was close to being empty. But at nightfall of Thursday 26 January Barcelona was an occupied city and the Model prison was its primary detention facility. A special regime of occupation lasted until 1 August, while the state of war announced by the army – which had been led into insurgency against the legitimate Republic three years previously – carried on until April 1948. For those who were defeated, the night of 26 January 1939 was to last almost forty years.

According to a reconstruction of the official figures made by the authors of Història de la presó Model de Barcelona (History of Barcelona’s Model prison – an extensive book published in 2000 and re-edited just a few months ago), at the end of 1939 there were some 12,745 prisoners in the Model, living in awful conditions. The state of the facilities was disgraceful, the list of diseases affecting prisoners was endless, and political repression was without doubt the main reason behind most of the executions, which totalled 1,618.

The extent of prison overcrowding was a cause of concern for Franco’s government, who came up with a system for reducing sentences through work. Prisoners who were not guilty of violent crimes and demonstrated good behaviour could work on the outside or in the prison’s workshops; in exchange they received a small amount of pay and a reduction in their sentences of one day for every two days worked.

Photo: Arianna Giménez

Above, Gabriel Gómez remembers his father Helios’s stay in the Model prison. Helios Gómez was an anarchist illustrator, painter and poet who painted the murals in the so-called Gypsy Chapel, reproduced below for the exhibition ‘La Model ens parla. 113 anys, 13 històries’ (La Model talks to us. 113 years, 13 stories).

Photo: Arianna Giménez

Intellectual redemption

One afternoon in 1948, the driver for the Minister of Employment (José Antonio Girón de Velasco) entered the Arnáiz art gallery in Barcelona. There he found Helios Gómez, a graphic artist and designer, poet, journalist, supporter of civil liberties and anarchist, together with his five-year-old son, Gabriel. “The guy wore riding boots, a grey suit, silver-plated v-shaped buttons and a huge silver hat. He was like an admiral” recalls Gabriel, in the living room of his home, a room decorated with his father’s pictures and prints. The child was awestruck by the driver’s outfit, he was like a character out of a comic.

The driver took his father to see Girón de Velasco, the minister, who tried to convince Helios to work for the regime, without success. Helios Gómez (born in Seville in 1905) had already spent time in the Model in 1930 alongside figures such as Lluís Companys and Àngel Pestaña; he was also in refugee camps in France and Algeria after the Spanish Civil War and had returned to the same prison between 1945 and 1946. Ten years before, in 1936, he had founded the Trade Union of Professional Draughtsmen of Catalonia, which instigated the poster campaign against Franco’s Nationalists during the war. A document his son Gabriel found in an archive in Salamanca almost half a century later described him as a “prominent left-winger, a spreader of ideas”. Given that he refused to work for the regime, he was sent back to the Model prison a few days later.

Gabriel Gómez remembers the day his father went in; as it was the feast day of the Virgin of Mercy, the patron saint of prisoners, children were allowed in to see their fathers. “They didn’t have beds, just a few mattresses”, he recounts. Although the overcrowding of the prison was down on the 13,000 prisoners there in 1940, there were still over 2,505 inmates sharing its unhealthy living conditions, more than three times the amount the architects had envisaged.

Helios Gómez was sick when he left the Model prison in 1954 and died two years later. Gabriel Gómez has researched his father’s life and works extensively, an exercise that began when he saw Helios mentioned in something written by Teresa Pàmies. This led to him a meeting with his father’s fellow inmates, militants from the POUM (Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification). “They received me very warmly and answered everything I asked them about my father, even though they preferred talking to me about the history of this country nobody used to tell.”

Brother Bienvenido Lahoz arrived at the Model prison in 1941. Serving as its priest, he was a member of the Mercedarian Order and enjoyed holding intellectual debates with the political prisoners. Nevertheless, he also tended to give short shrift to arguments that were not to his liking. Knowledgeable of Helios Gómez’s artistic capabilities, Lahoz asked him to paint a chapel in the first cell on the first floor of the Model prison’s fourth gallery, just next to the cells for those condemned to death. The piece he completed in 1950 has at its centre the Virgin of Mercy – the patron saint of prisoners and of Barcelona, the latter title held jointly with Saint Eulalia – holding Jesus as a child, who has a paper pinwheel in his hand. At her feet there is a group of men in chains and on the opposite wall, where the door is, there is a chorus of angels. The authorities of the time would have liked the work even more had the men in chains not been portraits of his colleagues from the POUM, and if the main characters in the scene, including the Virgen, had not all had features characteristic of gypsies – a people Helios Gómez belonged to.

This space, known as the ‘Gypsy Chapel’, was painted over in white in 1998, while Núria de Gispert was in charge of the Catalan Government’s Ministry of Justice. Later, when Montserrat Tura was at the helm of the same department, the cell was closed off. Now, attempting to look in from outside you cannot even get a glimpse through a crack. Gabriel Gómez explains that thanks to help from SOS Monuments he managed to get in touch with the City Council architect to declare the large central inspection room – which connects directly with the chapel cell – as an element to be saved. Deputy Mayor Jaume Asens has provided assurances that the chapel will be protected, “The plan is to remove the paint that’s covering the mural and to preserve it.”

“We want to offer visual accounts of the suffering that occurred in the Model prison. It’s something that hasn’t been talked about that much, but in reality it’s one of our society’s most terrible places”, Jaume adds. In the process of deciding on future uses of the premises, the proposals on the table include one from the local authorities to create a history centre, and there is an idea from Helios Gómez’s son to permanently establish a museum of political art.

A new generation

Beginning in the 1950s, once the United States and the Vatican started opening the regime’s doors to the world, the Franco dictatorship was unable to maintain the harsh levels of repression seen previously. The political prisoners continued to arrive, but what with the reduced sentences for old-timers as well as remissions for good behaviour, the Model prison gradually became less crowded, going from 8,685 inmates in 1941 to 1,832 in 1955, and continuing with a relatively stable population from then onwards. Those who had been imprisoned in the immediate post-war period were replaced by a new generation, chiefly consisting of younger common criminals and, as of the 1970s, members of political groups that opposed Franco.

The dictatorship continued with its efforts to mould the morals of society both inside and outside of prisons. The 1954 reform of the so-called ‘Law on Vagrants and Wrongdoers’ – a law originally created during the Republican presidency of Manuel Azaña in 1933 – expanded the legislation to include homosexuality to the existing crimes of begging, nomadism and prostitution. Later, in 1970, the Law on Vagrants was replaced by the Law on Dangerousness and Social Rehabilitation, which included activities such as dealing or consuming drugs, the sale of pornography, prostitution, pandering and illegal immigration as crimes that could incur prison sentences. And homosexuals did not benefit from the pardon of 25 November 1975 or the amnesties that came in the two years that followed. The Model prison had inmates who were there as a result of their sexual orientation until 1979.

With Franco on his last legs and the new law in force, the authorities began throwing in jail anyone they deemed to be a social or moral risk: political dissidents, people whose sexual and amorous lives were disapproved of, people suffering extreme poverty, gypsies with no fixed abode and, towards the end of the 1970s, people addicted to drugs. It was during the years in which political prisoners lived alongside regular prisoners that the latter group created COPEL (the Prisoners’ Struggle Cooperative) to demand the same amnesty that the political prisoners had received. Their view was that they had been imprisoned under the laws of Franco’s regime and therefore their incarceration was illegal under the new democratic regime. However, they were not successful. There were prison riots and later on, at the end of the 1970s, heroin was to have devastating effects.

Former prisoner Eduardo Borràs talks in this report.

Photo: Arianna Giménez

Daniel Rojo describes his stay in the Model Prison in this report.

Photo: Arianna Giménez

Accounts from inside

Daniel Rojo was held at the Model between 1981 and 1983, then again between 1984 and 1989, and finally between 1991 and 1993. He has been teetotal for over fifteen years and claims to have kicked eleven addictions, including heroin. Sitting in the entrance of a relatively fancy hotel near Plaça Molina he explains “those days really were bad; almost all the inmates were junkies and almost all of us had HIV”. With methadone treatments not introduced until the 1990s, the prisoners had to be very resourceful to get their hits. “A needle lasted us a month. We would file them down because with so much use they’d get broken or blocked, and so we had to stick wires in.”

When Rojo was first sent to the Model prison he was nineteen, had already robbed dozens of banks and had plenty to show for it. “I showed up in front of the prison officers with a Cartier gold chain with Dalí’s Christ on it and a Rolex Cadete. They told me to leave it all at the entrance, as inside it’d get stolen. I thought that if I left it there, I’d never see it again, but inside at least I could try to defend myself.” All Rojo wanted was to preserve his status.

He recalls how the prison officers were still very militarised. “High green boots, silver hat, stripes (silver for temporary staff, gold for those who were permanent),” Their relationship with the prisoners was not good. “If you treat a prisoner like a dog, he will behave like an animal”, Rojo summarises. He adds that if prisoners are made to go the toilet in a hole from which rats jump up to bite you, this likewise has a negative effect on behaviour.

The demilitarisation began with the new penitentiary law of 1979 and the handover of control to the Catalan Government in 1984, culminating eventually that decade with the introduction of psychologists, doctors of both sexes (as opposed to just male doctors beforehand) and the implementation of face-to-face and conjugal visits. Going into the 1990s, the introduction of methadone finally brought some calm after the Model prison’s most turbulent years. It was in those years that Jaume Asens began visiting the prison as a lawyer working only for legal aid (“for ideological reasons”, he clarifies). Politicians had then been promising and putting off the closure of the prison for quite some time. “Prison is for the poor; the criminal system has selective tendencies”, Asens points out. For the main part, visiting the prison he encountered poor people, sick people and drug addicts.

Even though the Catalan Government became the main competent authority for prisons, many laws are still made in Madrid. In 1995, the BOE (the Official State Gazette) published the new criminal code, the first in Spain’s new democracy. Since then it has been reformed some thirty times, lengthening sentences and adding justifications for sending people to prison, going so far even as ‘a permanently reviewable prison sentence’. According to a report from 2015 by ROSEP (the Network of Prison-Related Social Organisations), it is getting harder to apply alternatives that favour rehabilitation. In 1975 there were 8,440 people being held as prisoners in Spain; in February 2017 there were 60,203. ROSEP’s report concludes that around 60% of Spanish prisoners are imprisoned for crimes of medium-level seriousness (theft, robbery, drug dealing), offences that do not cause a high level of social alarm and would be better dealt with by measures that did not lock the culprits away.

At the turn of the new century Eduardo Borrás was sent to the Model prison, accused of robbery. There he was at times living in a cell with four other people. After a year and a half he was sentenced and transferred to Brians prison. “In the Model prison you quickly get burned out. Some day the prison officers might come into your cell looking for chocolate, and if they didn’t find any they’d strip you naked, as well as completely messing up your cell”, he recalls. Meanwhile Francesc López, who worked as a prison officer there for twelve years, laments the fact there are still some people who could believe the current officers work like those of Franco’s regime.

What is in store

In January this year, a week after the final agreement to close the Model prison was signed, the owner of the building at 151 Carrer Entença began rescinding the residents’ contracts, saying they would not be renewed and putting the flats up for sale online. Since then the residents have got together and have been protesting to the City Council in search of a solution. The owner has been closing the flats up with metal sheeting each time he manages to force a resident out.

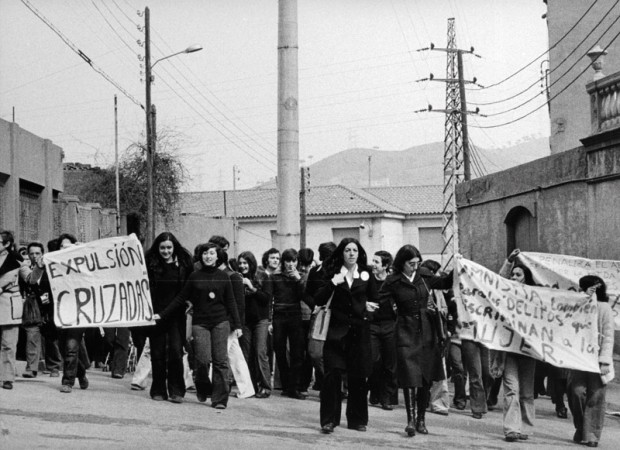

Press conference with tenants threatened by speculation in the vicinity of the Model prison. The man with his arm raised is Joan Gómez.

Photo: Arianna Giménez

There is just one resident whose contract is not temporary: Joan Gómez, who is retired, and who takes care of receiving the media on behalf of the residents’ collective in his small living room on the first floor. There on his table he has laid out all the press coverage they have been given, and with clarity and precision he explains their alternatives. “Either the City Council buys the building – which is unlikely as it’s a private owner and not a bank – or we create a housing cooperative to manage the rents.”

While he sees himself as someone with left-wing politics, Joan and his neighbours had never been such a community until the fax messages started arriving telling them to leave. “I’ve been living here since 1981. For years we’ve been calling for the prison to be closed and now that we’ve got there, a load of new problems come up. Off go the prisoners and down come the vultures”, Joan sums up. Jaume Asens is proposing to combat gentrification by building social housing apartments in the part of the Model prison premises that runs along Carrer Nicaragua, where for a time there was talk of creating a hotel. The neighbours’ associations are voicing their support for this, reiterating that there has to be a greater balance between public and private supply.

A group of residents having their photograph taken outside the entrance to the prison the day before it closed.

Photo: Arianna Giménez

The Model prison was an obsolete facility. Amand Calderó, Director of the Catalan Government’s Penitentiary Services, states that it would have been necessary to spend 25 million euros in order to bring all its areas into line with current prison requirements. As such, an agreement to close it was made with three of the five trade unions (the two who would not sign being UGT and ACAIP). As well as working at the Model prison, Francesc López is also a member of the prison workers’ trade union ACAIP. The Model prison is the only prison in Catalonia where this trade union has majority representation, and the feeling among its members is one of disillusion. “For years they’ve been promising to build a pre-trial detention centre in Zona Franca, but in the end we haven’t been able to choose where we’ll go next”.

López entered in 2005 “with 2,100 inmates” and is certain that the prison could have continued operations until the promised open prison and pre-trial detention centre in Zona Franca were ready. However, the agreement between the City Council and the Catalan Government gives opening dates of 2021 for the open prison and 2025 for the pre-trial detention centre, with construction costs of €35 million and €75 million, respectively. In this agreement, from 2009, the authorities agree to allocate the land in Zona Franca in order to close Barcelona’s two other prisons: the Wad-Ras women’s prison and the Trinitat Vella open prison. Calderó says that the €35 million to build the new open prison have already been ring-fenced. It remains to be seen what can be gained from the land at Trinitat Vella in addition to the €5.5 million the City Council has already paid for the construction of social housing apartments, as the complete lot is yet to be made available.

The issue – which the Director of Penitentiary Services is not overly concerned about – is that if over the course of fifteen years nothing is built in Zona Franca, the City Council recoups the land. Prison officer Francesc López is clear about what he thinks will happen. “If they’ve managed to put all the pre-trial prisoners in Brians 1, that’s where they’ll stay, and at Zona Franca they’ll only build the open prison. They’ll take the women from Wad-Ras to Brians 1, too, as there’s a large women’s section there. That way they’ll save money.”

Covering distances

Prisoners’ families living in Barcelona or its immediate perimeter were the first to feel a negative impact from the change. They are forced to choose between finding a private vehicle to get to the prison, taking a bus from Sants station, or getting a train to Martorell and then a bus from there. In any case, the amount of time and money they have to spend on travel has risen dramatically.

As for the problem of transport for the defendant’s legal representatives, Penitentiary Services signed an agreement with the Bar Association in order to establish a telematic communications system. So far, eight conference rooms have been installed at Brians 1. These are a distant cry from the rooms provided for legal visits that Jaume Asens remembers, “which were significantly worse than what you see in the movies”. The lawyer and the client could make contact visually but not physically, and had to talk through a grille surrounded by the din of other people’s shouting.

The Deputy Mayor has concerns about whether lawyers working for legal aid who live or work in Barcelona are going to make the effort to travel to see their clients. “They’re poorly paid” he claims. “It was clear back in my day that not enough was done to help inmates, especially after the trial.”

Calderó gives his assurances that the closure of the Model will not entail overcrowding problems in the rest of the prisons. In fact, he describes it as an opportunity to reorganise the prison system to scale with the city and country. “We didn’t want to jump off the deep end. When the Model prison was open, Catalan prisons were at 67% of their capacity; once it closed the figure went up to 73%” says Calderó, re-checking his figures on a printout. “The forecast is for Brians 1 to go down from 85% to 71% in September.” At the ACAIP the talk is not so much of the deep end as it is of Russian roulette. “In the [Catalan Government Justice] Department they knew that neither the prisoners nor us employees would be in agreement with the change, and that problems could arise.” In the end there was no strike and tensions did not rise, with the exception of the odd altercation with a prison officer and a young prisoner climbing onto the roof in March.

After so many years, one question to ask is what has the prison done for the city? Has it cut the number of repeat offenders? Has it achieved greater success with prisoner rehabilitation? Things have gone very well for Daniel Rojo since he left the Model prison and he is happy to talk about his time behind bars, although he admits that rehabilitation is very difficult. “When I got out, I had no kind of training whatsoever. I could rob banks, I knew how to do that very well, but not much else. Work, love and family: if you’ve got those three things, everything else in life is easier.” Or perhaps it would be worth discussing social options to obviate the inequality that results from having been to prison and the permanent mark this leaves on people. Eduardo Borrás’ face takes on a sad look as he thinks back upon his time in the Model prison. Sipping on a can of citrus-flavoured water, he recalls how when he was inside he had the urge to send letters of complaint about the prison conditions “as far as the Pope in Rome”, but as soon as he left he simply thought “so long guys”.

Amand Calderó, the Director of Penitentiary Services, claims that seven out of every ten inmates do not reoffend, “but we can’t be content with just that; there’s still a lot of work to do.” At the other end of a telephone line, speaking from his office, Jaume Asens remembers the Model prison as place with people living side by side in an atmosphere that was “hostile, stigmatising, infantilising and preventive of personal autonomy”. And Foucault (in the same work cited earlier) maintains that “prison cannot fail to produce delinquents. It does so by the very type of existence that it imposes on its inmates: whether they are isolated in cells or whether they are given useless work, for which they will find no employment.”

One of the prison blocks and its cells turned into a gallery for the exhibition ‘La Model ens parla. 113 anys, 13 històries’, which can be visited as part of the open doors event that goes on until November.

Photo: Arianna Giménez

Selfies in the cells

Although he had never entered the Model prison, Francesc remembers when he demonstrated in front of it in support of Lluís Maria Xirinacs, who stood in front of the prison for twelve hours every day for almost two years during the transition to democracy, calling for an amnesty for political prisoners. Today – 5 July 2017 – this sturdy man with agile fingers and white hair is out with fellow members of the Watercolourists’ Collective of Catalonia; they are on one of their Wednesday excursions to paint the city, this time coming to the patio where the prisoners used to do sports. One of his companions remarks “you’ll soon see how the painting is prettier than it really is”. To one side of them, busy moving furniture that is to be sent to other prisons are workers from the CIRE (Centre for Rehabilitation Initiatives), inmates from various open prisons who are paid minimum wage.

If like Francesc and his watercolourist friends you would like to experience the Model prison, anyone can sign up and book a visit to see the most symbolic parts of the premises as well as the exhibition “The Model Prison talks to us. 113 years. 13 stories”, commissioned by Agustí Alcoberro, which is part of a series of open-doors day events that is running until November.

The residents wander through the fifth gallery, the cells of which have been decorated to tell their respective stories. Some of them are using selfie sticks to photograph themselves in front of the cell that describes the prison riots in the time of El Vaquilla (a famous criminal who was at the Model prison in the second half of the 1970s). The room is a mess, with mattresses, chairs and blankets, and dirt and misery. Opposite it is a recreation of one of the original cells of 1904, designed for a single prisoner, clean and exemplary, something like the cell where Ferrer i Guàrdia would have awaited his death sentence.

Beside Francesc – who has finished his watercolour, which is indeed prettier than the reality it reflects – an open prison inmate who now has to go to Brians prison every night to sleep signals around him and points out “They’ve left this looking very nice, but don’t fall for it, the Model prison wasn’t like this.” On the way out of the premises, past the three security gates and in the outer courtyard, the Justice Department has set up a small stand – something like a museum shop – where you can by baskets, bags, notebook, towels, fabrics and so on, all manufactured by prisoners. On the labels of these products it says: “Made in CIRE”.