It was a Saturday, 29 April 1967, when Roberto Lahuerta Melero went to the cinema for the first time since he’d arrived in Barcelona four years earlier with his family, from Ainzón in Zaragoza. His exhaustive accounts of Barcelona’s cinemas reveal a nostalgic memory filled with infinite gratitude for all the elements of that landscape. A picture that begins in the Turó cinema, where he attended a double feature (La ciudad no es para mí and La carga de la policía montada), but which could apply equally well to a large part of the converted theatres which, as cinemas, provided affordable leisure and cultural settings for the working classes.

Over the following decades, the historical establishments – neighbourhood cinemas and other, classier, first – run downtown cinemas – came up time and again against the challenge of survival: the tastes and habits of the public in matters of entertainment underwent enormous changes and the cinema as a form of leisure or even a lifestyle struggled to adapt to the new facts of life. Throughout this struggle, and over and above the overpowering creeping commercialism, alternative circuits have been established that have allowed new experiences for cinema-lovers while preserving the best of the traditional ones and have even, in some cases, managed to recover the local roots of the old neighbourhood cinemas. We look at this phenomenon through the eyes of some of its main protagonists.

One of Lahuerta Melero’s books – Barcelona tuvo cines de barrio (Editorial Temporae, 2015) – conjures up the old neighbourhood cinemas in terms like these: wooden and/or velvet walls, an elderly lady in the ticket office, uncomfortable, creaking seats, the tap water in the toilets with that taste of chlorine, everyone having their tea or supper among the audience – ‘the pleasure of eating a sandwich and some fruit in between films is something I still miss’ –, loud comments, some wittier than others, about what was being shown, and the vestibules like improvised crèches full of children bored with the grown-ups’ films. Those cinemas were an important sign of identity of Barcelona’s neighbourhoods at a time when, apart from bullfights and football, society had few means of entertainment.

The neighbourhood cinemas worked like second-run cinemas, with double features of films that had already been dropped from the first-run theatres. In those days you could go in at any time, halfway through the film, and wait until it started again to see the bit you’d missed. The large first-run theatres like the Urgell or the Novetats, with seating for more than 2,000 people, had exclusive rights for the province or even for Catalonia. Octavi Martí, Assistant Director of the Filmoteca de Catalunya, remembers that at weekends buses came from all over the country to see West Side Story, for example. Exclusive rights meant that a lot of films stayed for ever in the cinemas, as people always came to see them, which meant that scheduling new releases was blocked.

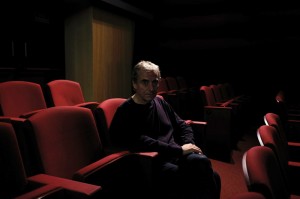

Octavi Martí, Subdirector of the Filmoteca de Catalunya and curator of the exhibition on show there about the Cercle A.

Photo: Arianna Giménez

The same year that Roberto Lahuerta Melero set foot in the Turó cinema for the first time to see La ciudad no es para mí, Pere Fages and Antonio Kirschner decided to launch an idea they called Cercle A, scheduling art films screened in the original language, in ordinary cinemas. They got in touch with Jaume Figueras, who was working as a publicist for CB Films. ‘They were friends of his and knew he was a very good businessman’, remembers Octavi Martí, who is also curator of the exhibition ‘La quadratura del cercle A’, which is being put on at the Filmoteca de Catalunya until 11 February to mark its 50th birthday.

The three partners made a market study to find the best-placed cinemas. The first one they looked at was the Publi cinema, located in what is now the Bulevard Rosa, which they turned into the first repertory cinema in Spain. Until then it had only screened children’s films and documentaries. They were given the evening programme to run and in 1967 they opened with Ingmar Bergman’s Dreams, which was followed by titles like José María Nunes’s Night of Red Wine and Roman Polanski’s Repulsion, their first film in the original language and at the same time their first real success.

From there they went on to screen auteur films at various cinemas whose name – except for the Publi – contained an ‘A’: Alexis, Aquitania, Arcadia, Arkadin, Ars, Atenas, Capsa, Casablanca, Maldà. At the Atenas, British productions with social content; at the Alexis, the most intellectually risky films (it was the smallest); at the Casablancas, films for younger people; at the Ars, double features with one old and one modern film; as for the more bourgeois Arcadia, ‘which was in Carrer Tuset, they put on more Rohmer films about married couples in crisis’ explains Octavi Martí, the curator of the exhibition.

They managed to give each cinema its own identity, so that the spectator could go there without knowing what was on, but confident that whatever it was they would enjoy it. Some time in the 80s they premiered a Chinese film, the first in this country for years. It was called Red Sorghum: ‘Completely unknown and hard to sell, it nevertheless drew 10,000 spectators. That was how much weight the Cercle A fan club carried. It wasn’t bad, it ensured production’, says Martí.

In addition, they innovated in the way they advertised the films, especially thanks to Jaume Figueras’s publicity skills. To get more people to see The Hairdresser’s Husband when it had already been on for a year and a half, they decided to invite the director (Patrice Leconte) and the leading actress (Anna Galiena) and put a barber’s chair in the entrance to the cinema. Anyone buying a ticket for the film got a free shave.

The rise of a new spectator

In this way, the Cercle A made a decisive contribution to the creation in Barcelona of a new film spectator. For Octavi Martí it was, in fact, ‘a spectator’s club with its own way of viewing films. A public that read subtitles quite happily and that understood that the cinema has an intellectual value that places it above pure entertainment’. And who got used to being given a film sheet with information about the film and reviews at a time when there were no film courses in universities or schools.

The director Ventura Pons in the office of his production company. In 2014 he began his adventure of buying a cinema, the Texas, and giving it a schedule and an identity.

Photo: Arianna Giménez

Sitting on one of those sofas where your knees are higher than your hips, Ventura Pons answers questions sometimes with few words, sometimes at length. He lights cigarettes that burn away between his fingers and drinks coffee as though it were water. When we ask him about the launch of his first film – Ocaña, retrato intermitente –, he answers at length: ‘I launched it 40 years ago, in June 1978, a few months after censorship disappeared. We filmed it clandestinely and it was like a snowball that grew when it entered the official selection for the Cannes festival’. It made its debut with the Cercle A. Ocaña bought flowers and they decorated the premiere with Manila shawls. ‘It’s a film that’s as if it were made now, because the message is still current’, says the Barcelona film-maker. And he ends his reminiscences with this sentence: ‘Film fixes things; the theatre doesn’t’.

Not long ago, in 2014, Ventura Pons set off on an adventure consisting in buying a cinema and providing it with a programme and an identity. When he was asked why, at this stage in his career, with his life settled, he ventured into this undertaking, Pons answered in headlines: ‘What led me to reopen the Texas cinemas was my commitment to life. My life is the cinema and the cinema is my life.’ A more prosaic explanation is that when he heard that Ricard Almazán was being laid off as scheduler for the Verdi cinemas after 25 years in the post, Ventura Pons saw the light: ‘I spoke to Almazán, now Captain Texas, and we got down to looking for cinemas’.

The film-maker, playwright and author unaffectedly describes the basic element of his cinematographic offer: ‘We haven’t invented anything, we offer re-releases like the ones there were when I was little, second runs, as they call them. They were good, nice and cheap. Three euros admission. What more can I say? All these things make people come back to the cinema.’ And he stops to point out that although they sell plenty of tickets, ‘unfortunately, the money goes to Montoro [the Treasury Minister]’.

Pons has been directing films and plays and writing books for 40 years. As we speak he seems to be in something of a hurry to end the interview. But when it actually ends, he forgets the time and invites us to take a look around with him in a little room belonging to his production company where he keeps original screenplays with his hand-written notes and crossings out – some by the censor, he tells us – and carefully handwritten yellowing family correspondence.

Pons remembers how the film offer and film consumption has changed in Barcelona society. ‘Until the 70s you could distinguish the films by the producer: Metro, Fox, Warner – he checks them off on his fingers. But nowadays they’re all the same. What’s more, they’ve moved audiences out of the centre of the city with the offer in large shopping centres on the outskirts. “Fast cinema”’.

The proliferation of centres equipped with a holistic offer in entertainment for an afternoon of family consumerism is something that comes largely from the United States. North-American society goes almost everywhere by car, it feels uncomfortable out of doors because it’s colder than here, and it’s quite happy to haunt enclosed, sometimes even underground shopping centres, unlike a Mediterranean society like ours, which prefers to walk about, to get out of doors. That business model began to get established in Barcelona in the 80s and was decisive for understanding the change resulting from the success of multiplexes in film consumption.

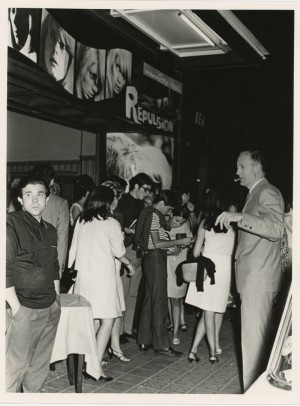

Members of the public at the screening of Roman Polanski’s film Repulsion, the first film to be shown at the Publi cinema in the original language, in 1967, when the Cercle A took charge of the scheduling and turned it into the first repertory cinema in Spain.

Photo: Filmoteca de Catalunya

Cercle A lasted a few years, until 1992. The reasons it came to an end, according to Octavi Martí, can be found in the very success of the project. ‘Other companies also saw there was money to be made and also started screening films in the original version, but not all of them had good judgement or knew how to sell what they were offering.’ The three people behind Cercle A didn’t own the cinemas, they weren’t that ambitious, and when businessmen who did and were started to do business on their turf they were overwhelmed. ‘They began to steal the names that they had managed to make popular’, says Martí. The commercial circuits, with their hegemonic cultural discourse, once again swallowed up an alternative project with their all-devouring market logic. ‘As a global phenomenon, the humanities have lost a lot of weight in general culture. People no longer feel uncomfortable if they haven’t seen a famous film’, says Octavi Martí from a little office at the Filmoteca de Catalunya. ‘Broadly speaking, curiosity has disappeared.’

Television, video and commercial judgement

The phenomenon of neighbourhood cinemas or second-run theatres isn’t so old, although it no longer exists in the form it took until the 80s. The excitement over adult movie theatres after the dictatorship and the recovery of other films that had been censored cushioned the fall in audiences slightly, but subsequent rapid advances in technology and fashions, the universalisation of television – and home video, which lets you pause the film to go to the toilet…– and, to top it all, the dominance of an industry that gave priority to financial returns over cinematographic quality or the social involvement of what was being shown in cinemas, put an end to those neighbourhood cinemas. With them went the chance to go to a double feature and meet neighbours, friends or classmates, as well as those conversations about the film during the week that used to be so common.

According to 2016 figures from the Observatori de Dades Culturals de Barcelona (Barcelona Cultural Data Observatory), which depends on the Barcelona City Council’s Culture Institute, in Barcelona that year there were 173 cinemas – 20 less than in 2010 –, which were used by more than six million spectators – as opposed to seven and a half million in 2010 – with a box-office turnover of more than 42 million euros – six years before it had been almost 55 million. Every day less people go to the cinema.

Vestibule of the Phenomena, a cross between a neighbourhood cinema and a large first-run theatre.

Photo: Arianna Giménez

‘Phenomena’, a hybrid experience

Nacho Cerdà, manager of the Phenomena cinema, remembers that it used to be possible to walk around the Barcelona neighbourhoods and ‘classify each cinema as first-run theatres, second-run theatres or repertory theatres. Each one had a different offer and now it seems everything has been homogenised in those shopping centres where practically 100% of the film offer is commercial cinema’.

In the same way as the Cercle A – screening in cinemas without owning any of them –, Nacho Cerdà began organising his Phenomena sessions in December 2010 in different Barcelona cinemas. Recovering great classics that have constituted a cinematographic pop culture in the modern iconic imaginary, they began to gain in popularity until in 2014 he opened his own cinema: ‘Every director’s or film-lover’s wet dream is to open that cinema where you can put on your ideal programme’.

A defender of the single auditorium, where all the audience gets together in the dark for almost two hours to watch the same story on the silver screen, Cerdà doesn’t like spectators having to leave by the emergency exit, for example. He feels they ought to leave by the main entrance again. The cinema experience shouldn’t end until you’re out in the street’, he declares. What is seductive about his project is that people should be able to go to the cinema and socialise, talking, having a drink… in short, taking part in ‘that sort of social event that has gradually been lost in the multiplexes’.

The films screened at Phenomena date from the 30s down to our own day. A mixture, as Cerdà sees it, of two concepts of cinema that at first sight seem antagonistic: the little neighbourhood cinema and the large first-run theatre. Recently Phenomena has been putting on more blockbusters than before. It helps to pay for the minority films, the ones that are ‘the apple of my eye’, as Cerdà confesses: ‘On one hand, films from the 70s that 20 people come to see and, on the other, Star Wars’.

Although it looks to the past, Cerdà doesn’t think his offer feeds on cinema-lovers’ nostalgia. ‘No. I’ve heard that argument a few times and I don’t agree. The cinema is ancient, you might think the act of going to the cinema is nostalgic now, but no. Here we just want to transmit the experience of the silver screen, the velvet, the single auditorium, the red carpet’. Cerdà says he often goes into the auditorium to watch the film just like any other spectator. ‘I love seeing how people react to the collective experience of seeing a film at the cinema and not at home’.

To Cerdà, ‘the survival’ (he laughs as he utters this word, as though to take the drama out of it) ‘of some cinemas, like ours or the Verdi, Girona, Renoir, Texas, and even the Floridablanca, has meant that there are people who still see the cinema in this way, as a philosophy’, and he points out that what distinguishes these cinemas from the multiplexes is, once again, trust. ‘Nowadays it’s not just a question of going to the cinema, people go for other reasons, too. These cinemas have a lot of faithful followers who don’t go just for a specific film, but, in general, just to see what’s on’.

It’s not an easy job. Nacho’s aware of the wear and tear involved in running a cinema. ‘You wouldn’t believe how hard eight well-organised people can work. We have to negotiate with distributors, keep an attractive programme going, see to the public and their needs and, of course, cover the expense of maintaining the premises. I can tell you, if I wanted easy money I’d work at something less complicated’, he says, without a jot of regret for the adventure he set out on three years ago.

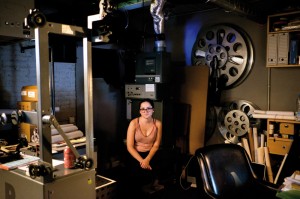

Xavier Escrivà, who since 2010 has been directing the Maldà alongside Natàlia Regàs. Escrivà began his long relationship with this cinema in Ciutat Vella as a spectator, when he was an employee at the Galeries Maldà, and later, at the beginning of the 80s, as an usher.

Photo: Arianna Giménez

It’s a tough life at the Maldà

Xavi Escrivà’s got everything ready for the session at ten past three. This time it’s the documentary film Kedi – ‘the Citizen Kane of cat documentaries’, according to the publication IndieWire, as the poster points out. As soon as the screening starts, he’ll start the stopwatch hanging round his neck. After one hour, 16 minutes and 47 seconds, Xavi will know the credits are starting and they’ll last two and half minutes, so that the film screening will end when the stopwatch says one hour, 19 minutes and 14 seconds. ‘Before, with the 35 mm reels, you needed two people working in the cinema, one upstairs changing the reels and one downstairs seeing to the audience’, explains Escrivà, and he gets sidetracked by memories of the two cue dots at the end of a scene on the old films, which let the operator know when to make the change. Nowadays, as the films are delivered to his Maldà cinemas on Blu-ray optical disks or on external hard disks, you don’t need two people for each showing, just Xavi with his Geonaute stopwatch.

As an employee back in the late 70s at the old furniture shop in the Galeries Maldà (in Carrer del Pi), Xavi didn’t miss a single session of Friday cinema when he left work in the shop. At the beginning of the 80s he was offered the job of usher. ‘Great! I’ll see lots of films. And what’s more, free’, he thought. Later the projectionist left and Xavi trained for the necessary qualification to become the supreme commander, the man in charge of the screening, a post he took up in the mid-90s. Later he took the crown and began to take charge of the programmes for the cinemas.

So going to the cinema changed his life. ‘Every Friday, when my friends went to see Bud Spencer and Terence Hill films, I came here to see Visconti, Fellini or Bergman’, remembers Escrivà. ‘My friends were amazed, but the thing is the films they went to see said nothing to me. The other cinema, though, got through to me, even though I didn’t understand it at first’.

Escrivà has worked at running a cinema during the worst years films have been through (and are still going through) in our country. He started when people stopped going to the cinema because they now had a television at home. This was followed by the rise of the multiplexes, the ageing of the audiences that still went to first-run theatres (or neighbourhood cinemas, like his), the decline of the independent film circuit, gentrification of neighbourhoods like Ciutat Vella, where the Maldà is, with the subsequent loss of the younger residents, and, more recently, the crisis of 2008 and the increase in VAT on cinemas to 21% (like luxury articles), which was the final blow for small cinemas like his. Even so, the Maldà, which opened in 1945, is still alive: ‘The distributors take 50% of the price of a ticket, 21% goes on VAT, and when you add on what we have to pay the SGAE (Society of Authors), we’re up to 75%. The remaining 25% has to cover electricity, taxes, the three of us who work here…’, explains Xavi, as a drop of worry appears on his brow.

The survival of the Maldà is decided each year, after checking the books and making sure the cinema can stay open at least another twelve months. ‘Four years ago, we took a beating in the months of September, October and December, we had enormous losses. Then we launched the campaign ‘Salvem el Maldà’ (Save the Maldà) and issued patron’s cards and other discounts and we came through’, remembers Escrivà.

The problem at the Maldà is to do with the future of its customers. Years ago, its manager says, both young and old people came to the cinema, but now the typical cinema-goer has aged. ‘Eighty percent of our customer profile is made up of women between the ages of 40 and 60. Audiences aren’t being rejuvenated and that’s a problem’. Xavi insists I mention the Maldanins sessions in my article, for parents to take their children to the cinema. The only future for these cinemas is to get the young ones back.

His audience’s loyalty is an encouragement to Xavi. When he describes how he talks to people about the films he plans to put on or the ones they’d like him to put on, his face lights up and his tongue runs away with him. ‘When I switch the projector off and come down from the projection box, we start discussing the film together’. And once again we see trust at work. ‘A lot of people come without knowing what we’re going to screen, but trusting that whatever it is they’ll like it, and that’s very satisfying’, he finishes.

The Zumzeig cooperative, in the vicinity of Sants station, is at once a cinema and a bistro. Above these lines, the ticket office and the vestibule.

Photo: Arianna Giménez

Zumzeig, a cultural and social tool

Scheduling isn’t easy. Anna Brufau is a partner of the Zumzeig cooperative, a cinema and bistrot in the area of Sants station which as well as offering an impeccable selection of auteur cinema, hopes to become a social and cultural tool for the neighbourhood. ‘Our cinema has to work with the industry, but we want to do so in other ways’, Brufau says. This certainly isn’t an easy target, because, as she explains, to be able to screen films in Spain you have to pay on average about 200 euros a film in broadcasting rights and be backed by a distributor who can take on the costs of communication and advertising, as well as subsidising the rest of the regular costs. The fact that you have to pay the amount mentioned means only those people with money and an infrastructure behind them can afford to screen whatever they feel like.

The films Zumzeig schedules run for longer than at other cinemas. ‘Independent cinema needs more time’, says Brufau. ‘A lot of the films we show aren’t backed by a communication campaign and usually succeed through hearsay. So if it takes three months for people to come and see it, we keep it going that long’. This approach clashes head-on with the industry logic of the film screening business, which works like a bulldozer. ‘What the commercial distributors want – barely four or five of the ones operating in Barcelona are independent – is for the public to turn out en masse for their screenings, and if a title doesn’t work in the first ten days, they take it off and that’s it’, says Anna.

Every week about fifteen films are premiered in Spain. Out of these, Brufau says only one or two are of interest for showing at Zumzeig. ‘And then we might find that of these one or two are distributed by a large company, especially if they’ve been presented at an important festival like Cannes. In that case, our cinema may not be of interest to the distributor’. According to Brufau, it’s getting easier to see these films at the festivals than in cinemas.

And festivals are common and are more and more specialised. One of them that collaborates with the Filmoteca de Catalunya and with Zumzeig when it’s held in Barcelona is the CineMigrante. Set up in 2010 in Buenos Aires as a political and cultural space, ‘it arose from the need to demonstrate that the language of film is also nowadays relevant to the phenomenon of migration’, says Martina Bernabai, a member of the project.

CineMigrante, like Zumzeig, sets out to create shared spaces, especially in a historical context ‘in which migrations and their management by the institutions are a challenge to the construction (or rather deconstruction) of new societies’.

Specialisation, though, isn’t the key to a project like Zumzeig, which is working to become a sort of cultural centre for the Sants and Hostafrancs neighbourhoods with the same object as CineMigrante: to transcend the cinema and become an instance of cinematographic but also political reflection that makes itself felt. ‘Specialisation goes against the idea of proximity’, says Brufau. ‘Of course, we want people from all over Barcelona to come, but we’re working to weave cooperation networks with other organisations in the neighbourhood, we try to make sure that audiences, art and ideas flow between the associations and, above all, we fight to break down the preconceived notion that these films are difficult to watch for most people in the neighbourhood’.

Working in committees helps. There’s a nuclear group that sees to scheduling and different committees with the time and the tranquillity to work on other important aspects of the project that call for fresh, creative ideas, such as the best way to educate people to combat the snob stigma of independent cinema, or the neighbourhood committee, which is directed at establishing relations with organisations and residents.

This philosophy of ‘neighbourhood construction’ is what the Zumzeig collective have tried to bring to the project in the last year, since they’ve been operating as a cooperative. Its owner, Esteban Bernatas, opened Zumzeig in 2013 and three years later he transferred the rights of use to the present cooperativists and retired to live in Paris. When asked about his models when he opened the cinema, Bernatas mentioned the ‘cultural exception’ that exists in France as compared to Spain. There it’s as though culture was part of a public asset that must be protected from an implacable neo-liberalism’. Brufau, on this point, says ‘We don’t want to be just a cinema; we carry out activities as a cultural centre and we show the films we show not for the financial returns we can get from them, but because we feel a duty to show them’. When asked why he followed the French model when he set up Zumzeig, Bernatas ventures that he may have borrowed from it in the type of schedule chosen, but that the idea of having a bar in the cinema is more like Berlin. ‘Although on second thoughts’ – Bernatas had visited his cinema a few weeks before answering that question – ‘I’d say that Zumzeig now is more Santsenc (from the Sants neighbourhood). A good sign.