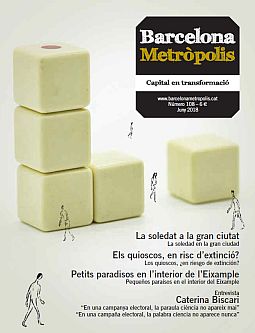

Living alone does not necessarily mean suffering from that, but over time social networks are weakened or lost, and people feel increasingly excluded and socially isolated. The situation is worse in the case of women, most of them on low pensions. Barcelona addresses the problem of loneliness among elderly people through public and charitable initiatives.

Gathering of Vincles (Ties) users at a café terrace on Passeig de Sant Joan. The Ties programme, which caters for more than 560 people, offers the use of a tablet with Internet connection as a tool to combat social isolation.

Photo: Dani Codina

In 2017, there were 1,410,000 women aged over seventy living alone across Spain, compared with 550,900 men in the same age band, according to the “Ongoing Household Survey” of the INE (the National Statistical Institute) published in April. The same survey indicated that 41.3% of women aged over eighty-five lived alone, compared with 21.9% of men.

In Barcelona there are a hundred thousand people aged over seventy who live alone. To cater for them, numerous programmes and projects have been launched to accompany elderly people with problems of loneliness. For its part, Barcelona City Council is drawing up an ageing strategy to integrate and underpin the work performed so far by the community.

Benita Rodrigálvarez is one of those people. At the age of eighty-four, she is the only person living in her home. She has set up her living room in the small hall, where she spends much of the day. Seated on her comfortable, practical sofa, her feet hang close to the ground: all ready to stand up. She has everything to hand. On her right, on a little doily-covered table, the remote controls and two phones with large keypads. She also has her medicines, some antacids and a cutesy little box of chocolates. On her left, a number of old volumes stand on a built-in bookshelf: 18 Years of Spanish Television, Stamps of Spain and the Holy Bible. The bookshelf also houses a calendar and a small almanac, both with the pages torn out to the current day. And opposite Benita and her sofa, the television stands in pride of place: “The telly’s a good friend,” she says. The adverts are on right now. Many of the ads suggest that to be happy you have to consume, produce, travel and discover sensations, be radiant and, above all, surrounded by people.

Montserrat Suriñach graduated in anthropology and teaches geriatric nursing as an associate lecturer at Barcelona University. She also practised as a geriatric nurse for around twenty years. Her opinion is that our society has a taboo about everything that isn’t young and beautiful: “What old age teaches you is that life also has another side. Death, vulnerability, decrepitude and dependence are elements we don’t want to see in our society, and so we turn a blind eye to them,” she believes.

You might be always surrounded by family or friends, or in an old people’s home, and feel lonely. Or be alone, but not feel that loneliness. And so quantifying unwanted solitude is difficult. According to the municipal population register, on 1 January 2016, there were 102,528 people aged over seventy living alone in Barcelona. The 2016 “Public Health Survey” reveals the following figure: 10% of people aged over sixty-five say they do not have anyone to talk to about their personal and family problems as often as they would like.

Such situations, the World Health Organization warns, advance the onset of mental conditions such as dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

Reclaiming the street

For Benita, after nearly seventy years married to a man who would not let her go out of the house with her female friends, becoming a member of the “Head Down to the Street” programme and meeting her first volunteer, Íñigo, really cheered her up: “I remember the first day we headed outside, and I was in my tank [her wheelchair], and when he hailed the bus and asked for the ramp… My, oh my! I thought I would never get on a bus again in my life”. Every Tuesday, two programme volunteers come to pick her up at home. They help up and down the stairway of the building with a mechanical chair, as there is no lift. It is a small flat on an alleyway in Barcelona’s Born district, near the Triumphal Arch.

Benita Rodrigálvarez, a user of the “Head Down to the Street” programme, in her flat near the Triumphal Arch, where she lives completely alone, the age of eighty-four. Being able to head out onto the street and meet the programme volunteers completely changed her life.

Photo: Dani Codina

“Head Down to the Street” was set up in 2009 as an initiative of the Poble-sec Community Organisation Coordinator as part of the neighbourhood plan, because of the problem they uncovered among the older people in the area suffering from reduced mobility, and mostly living in old buildings with no lift. The programme is now funded by the Barcelona City Council Health Department, and has been run by the Red Cross since the City Council and the charity reached an agreement in 2013. “Head Down to the Street” now covers 24 neighbourhoods in the city.

The volunteers take Benita to the Old People’s Day Centre (or “to school”, as she says). Benita loves playing the card game cinquillo and has taught all the other women at the centre the rules, but admits that she has kept the winning strategies (“the tricks of the trade”) to herself. They also go to the bank (she has to turn up every five months to prove she is still alive and continue receiving her pension) or to the hairdressers, and says she is really going grey now. Begoña de Eyto, the coordinator of the “Head Down to the Street” programme comes with us, and tells Benita not to worry, that grey hair is all the fashion these days. Benita cracks up laughing. She says she was born laughing. Later, out in the street, Begoña explains that because Benita is so stubborn, she sometimes goes out on her own without the organisation’s help. When asked how she gets up the sixty stairs back to her flat on her own, Begoña replies that she climbs up on all fours, using her hands.

Life stories shape the feeling of loneliness in the final stage: old age. Benita left her job at a shoe shop on Carrer del Call when she was 14, to look after her mother who fell ill. When she died, a few years later, she got married. She looked after her husband all his life, until in the final years she had to get him out of bed, out of the bath, lift him up off the sofa. And in the end she did her back in.

She doesn’t go to bed until dark: “At night, as I go round closing the windows and turning the lights off, I feel that everything is so sad… and that I’m all alone. But then I think that at least Benita [in other words herself], who has always looked after everyone, now has someone looking after you. It’s a silly little thought, but it gets me by,” and she gives herself a couple of kisses.

Begoña explains that when “Head Down to the Street” learns of a user who is feeling lonely, they make the effort to forge ties, and “make sure the volunteer and user establish an emotional bond”. They have eighty-four people signed up to the programme. As Begoña says, “it might not seem like a lot, but it’s a huge impact on the users

Flowers before bread

Berta Méndez has just turned ninety. She lives alone in a flat on Travessera de les Corts which luckily for her does have a lift. She has had a hip operation, and recently had a fall at home and broke her coccyx: “If it weren’t for Reyes, I wouldn’t leave the house”. Reyes Carles is aged 72 and has lived alone for the last four years, since her husband died. She is a volunteer at the Friends of the Elderly foundation: “I would pay to do it, but hey, it’s free”. For two and a half years now, Reyes has gone every Tuesday to pick Berta up at home: “What you have to do as a companion is be empathetic. Not treat people like they’re children, but respect them and establish bonds of friendship,” Reyes explains.

Reyes Carles, a Friends of the Elderly volunteer, with Berta Méndez, who she has been picking up at her home in Les Corts every Tuesday for two and a half years. Reyes also lives alone.

Photo: Dani Codina

Josep de Miguel teaches the Master’s Programme in Social Gerontology at the UB (University of Barcelona) and is the director of Inforesidencias.com, a website that advises families looking for an old people’s home for their relatives: “As a general rule we’re not good at looking after elderly people, maybe because we have never had 18% of the population aged over sixty-five,” Dr de Miguel says. “And so we tend to infantilise them, as those are the only behavioural patterns we associate with caring: looking after children”.

Berta holds on to Reyes’s arm to cross the wide pavement on Travessera de les Corts: “I’m scared of falling,” Berta says. When asked about her relationship with Reyes she continues: “She’s given me a new lease of life. We go for a little walk and tell each other things. She knows all about my two children, my four grandchildren and my four great grandchildren”.

As well as chatting, and searching the neighbourhood shops for the best camphor to treat the shawls she has had since time immemorial, Berta says that what she most enjoys is sitting by the window, on the two cushions that help her to stand up again afterwards, with the television on, watching the people come and go at the Lidl they have just opened opposite: “I see people come out, and I like to imagine what they bought, why and who for”.

Friends of the Elderly offers companionship to nearly a thousand other people, living both at home and in care, throughout Barcelona. “Flowers before bread would be the motto,” says Albert Quiles, the Managing Director of the organisation. “Emphasising the emotional, relational, even spiritual side, to avoid a person’s social demise”.

Political approach

Albert Quiles warns that they are short of data. Specifically to provide tools, Friends of the Elderly set up their Loneliness Observatory a year ago, to mark the organisation’s thirtieth anniversary. “Meetings, conferences and working parties to understand the relationship between loneliness and the different points in a person’s life, poverty, gender and migratory movements, and to understand better how the problem will evolve in the future,” Albert explains.

21% of Barcelona’s population is aged over sixty-five. By 2030, once the children of the baby boom have become the old folk of the baby boom, in Barcelona one in every four people will be more than sixty-five years old, according to city council forecasts.

Given the lack of data to analyse the problem, and the numerous different services and schemes, the council’s social rights department has been devising an ageing strategy over the course of the year: “Our focus is on an intergenerationally complex city in 2030, with gender justice, and that cares for the different stages of life,” says project leader Natàlia Rosetti in summary. “And so we have to integrate all the services and policies that currently exist”. The strategy, which aims to list what is already being done, and define what needs to be strengthened in the short and long term, sets out proposals such as the reorganisation of the remote assistance service to achieve a more personalised relationship, home refurbishment (since lifts cannot be installed in all buildings), or the integration of community and healthcare services.

The feeling of loneliness cuts across all sectors, but the risk factors of social isolation are more connected with class, gender and origin. Natàlia describes the profile they have managed to draw up with the limited data they have available: “Women who live alone, with no family or whose family lives a long way away. And also migrant men and women. They tend to rent rather than own their homes, have a lower income and limited education, which deprives them of the tools to seek out information, and so increases their isolation,” she recounts.

One of the many initiatives that will be needed to help link up the forthcoming ageing strategy is the Radar project. Founded in the neighbourhood of Camp d’en Grassot ten years ago with the aim of bringing the city council’s social services into closer contact with the general public, it has now built up as many as 1,063 users, 78% of whom are women, with 653 of them living alone. Rosa Rubio is the leader of a project that this year, its tenth, will have established a presence in fifty-three neighbourhoods: “Radar is based on citizen engagement and contextual empathy for older people,” he explains. It is the radar network (agents such as neighbourhood bodies, public services and resources, as well as local residents, pharmacies and shopkeepers) that keeps an eye on whether people living alone are all right, if there has been any change in their routines: “The neighbourhood is the smallest unit of action for older people, and so our aim is to create social ties through a personalised response”.

Right now, 1,244 shops, 527 pharmacies and 1,571 local residents belong to the project’s radar network: “When they report, a group of professionals evaluate the medical situation, and others maintain contact with the user,” Rosa explains. And as she points out: “Always the same volunteer, to create and maintain the bond”.

Chatting and sending memes

The youngest of the projects in this regard is known as Vincles (Ties). The pilot scheme ended in March 2018, and it now covers more than 560 people. The initiative won first prize at the Mayors Challenge 2014, a competition funded by the Bloomberg foundation that aims to “encourage cities to develop innovative ideas”.

The aim of the Ties project is to use a tablet with Internet connection as a tool to combat social isolation. By the end of this year they will have staged more than a hundred and fifty workshops to familiarise users with the tablets and the Ties app. The idea is that they relate to one another through a messaging system, and with the social fabric of the city through the social and cultural agenda that the app provides. The monitors suggest activities to the users, and also look for activities where they can accompany them. Sometimes just meeting for a coffee is enough.

Six Ties users meet up one morning in May at a café terrace on Passeig de Sant Joan. Many of them were strangers before they discovered the project. They drink different types of decaf coffee and chat, talk about their lives and their worries, such as one of them who lives on Carrer de València and Castillejos, and another on Provença and Lepant. They say that they don’t know anyone who lives in their buildings, that they are all tourist apartments, and recall that they were born in the house where they still live.

A couple of them have brought their tablets, and take photos of the gathering which they share straight away. They discus with irony and affection the photos of the breakfast that a fellow user uploads religiously every morning, and joke about a somewhat shocking meme showing someone throwing a bouquet of flowers into the crowd at a funeral, with the text: “Who wants to be next?”. They laugh heartily at that one. At the end of the day, they meet up to do what everyone does: to share their troubles and joys, to gossip and socialise. They don’t need much more than just not to be alone.

The Barcelona City Council remote assistance service helped more than ninety thousand people last year, women in 72% of cases. The technical staff equip the homes of elderly people who live alone with a device that connects directly to a switchboard by phone, and also by pressing the red button on a pendant that they have to wear at all times, or simply have to hand. Thanks to the pendant, her “medal”, Berta was able to notify them and they sent an ambulance when she fell and broke her coccyx. Nonetheless, most of the calls they receive at the remote assistance switchboard are not emergencies, but instead start with the words “no, no I haven’t had an accident… I pressed the pendant by mistake…”