From an evolutionary perspective, loneliness has been defined as a desire for social interaction. It’s a psychological and social condition that includes emotional aspects, cognitive aspects and a discomfort that we should see as the result of insufficient social support. Loneliness reflects our vulnerability and our need for others.

Elderly individual sometimes feel that they no longer belong in their environment: their family, their neighbourhood, their city… This is one of three great crises tied to aging.

Photo: Dani Codina

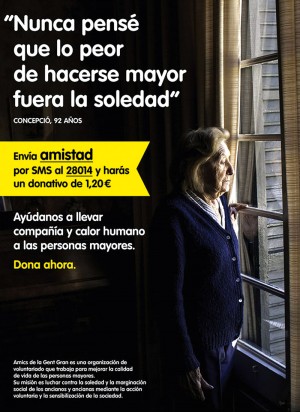

Loneliness is a problem that has made a big entrance into public debate in recent years, probably like never before. For some time, metro stations have housed posters from Amics de la Gent Gran (Friends of the Elderly) that read “I never thought the worst part of growing old would be loneliness.” The Spanish Law on Dependency also came into force in 2006 with advertisements in the same vein: “you’ll never feel lonely again.” This issue has been well-known for some time, and many measures have been taken to deal with it. The city of Barcelona addresses it through initiatives by third-sector organizations and municipal services –such as Teleassistència (Telecare), Radars and VinclesBCN (BCN Ties)– in addition to participatory spaces like clubs, civic centres, libraries and a broad range of cultural activities. But what does loneliness mean for the city, its neighbourhoods and its neighbours? How does it impact our individual lives?

According to the dictionary, the word “loneliness” can be used to define a series of states. One sort of loneliness is associated with wealth or creativity; it’s often defined as voluntary, a positive feeling of being in the company of ourselves. Then, there’s loneliness associated with discomfort, with feeling alone, with the desire for a type of social support that doesn’t correspond with what we receive or what we feel we deserve. Therefore, being alone can be associated with either positive or negative feelings; we can also feel loneliness when surrounded by others. In addition, loneliness can be social or emotional. Social loneliness is defined by the absence of a network of friends and acquaintances, while emotional loneliness refers to a lack of close confidants. Finally, we should differentiate loneliness and social isolation: the first is a subjective feeling, while the second is defined by an objective lack of social interactions. It’s the opposite of social integration.

From an evolutionary perspective, loneliness has been defined as a desire for social interaction. It’s a psychological and social condition that includes emotional aspects, cognitive aspects and a discomfort that we should see as the result of insufficient social support.

This article will focus on loneliness as an increasingly concerning source of suffering.

The three great crises in the process of aging

Loneliness among the elderly has been associated with three great crises we often experience as we age: an identity crisis, an economic crisis and a crisis of belonging. The identity crisis involves older individuals who feel that they’re no longer who they once were. The economic crisis affects those who suffer because they can’t do what they would like to do. The crisis of belonging affects those who feel like they no longer belong in their surroundings: their family, their neighbourhood, their city… The world is changing in a way that excludes the elderly, who are faced with the difficult challenge of adapting to keep from being left behind. We should also remember that we live in a society focused on the values of youth. Our society is ageist –it discriminates according to age– and it includes a great deal of prejudice against the elderly, making them invisible and turning its back on them.

We’re used to thinking that a Mediterranean country like ours is focused on social and family life. The fact is, however, that loneliness is an especially serious problem in the south and the east of Europe, more so than in the centre or the north. This north-south division has been broadly studied. As a matter of fact, it’s the high expectations placed on our social surroundings –for example, our expectations on how often our children should visit us and care for us in our old age– that creates a discrepancy between the social support we expect and what we receive. As we have already stated, this discrepancy is the root of loneliness.

When speaking of northern Europe, we have to refer to The Swedish Theory of Love, a recognized documentary from 2015 by Italian director Erik Gandini that paints a very peculiar picture of Swedish society. It shows us that many people in Sweden live alone, have children alone and die alone. It explains that this way of living stems from the political desire to achieve greater quality of life by helping individuals achieve true independence and self-sufficiency. The images and messages provided by the documentary and the stories it tells refer to a way of living and a series of state structures that allow and permit this. Beyond how accurate or impartial this vision of Swedish society may be, the documentary causes us to wonder: is this where we’re headed, as Mediterranean and sociable as we are? Is this where we want to end up? In Sweden, due to of the number of individuals who die alone at home, municipal governments have created a department in charge of identifying them, managing their affairs and inheritance and searching for possible relatives. Meanwhile, in Barcelona, in 2008 social services in the Camp d’en Grassot neighbourhood found that an elderly individual had died alone at home and no one had noticed. As a result, the Radars program was created to reinforce networks of neighbours and to prevent such deaths from ever going unnoticed again in our city. These are different ways of responding to the same phenomenon that create different kinds of cities.

Our society places a great deal of importance on the idea of social independence; this can be seen in the IKEA campaign “welcome to the independent Republic of your home.” As individuals, when we’re born we’re dependent on our parents in order to survive, and we gradually gain independence in certain activities. When affected by circumstances such as disease, we temporarily or permanently depend on others. But in general, we like to think that we achieve independence as adults.

Nevertheless, at most we reach a state of interdependence, and it’s important to acknowledge, accept and coexist with this relative dependence that ties us to others in order to live and survive.

Judith Butler, who has recently given several conferences at the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona (CCCB), noted that interdependence refers to the need to create a community, reminding us that as individuals we continue to be vulnerable throughout our lives. Today, vulnerability isn’t a growing concept, but it does provoke compassion. In this context, we would like to reconnect with the issue of loneliness, which refers to our vulnerability, and our need for others in order to feel well. We’re familiar with loneliness among the elderly, and it’s easy for us to imagine, to understand; it evokes a thoroughly human feeling.

Poster from an advertising campaign by the Amics de la Gent Gran (Friends of the Elderly) Association in metro stations in Barcelona.

Calling a feeling by its name

We’re familiar with loneliness because of our personal experiences, what others tell us and what we read. We seldom speak with those around us about their feelings of loneliness, or our feelings of vulnerability and interdependence. But we often come into contact with others’ loneliness indirectly through things like messages or telephone calls. Those that work with the public at medical centres or in stores, or even those of us that walk the streets or take public transportation, are perfectly aware of the casual conversations we have as a result of a non-explicit feeling of loneliness… What if we were to bring an end to this taboo, and to start to share this feeling by calling it by its name?

Through the many projects we’ve organized with the UAB’s Fundació Salut i Envelliment (Health and Aging Foundation), I’ve been able to observe and interview elderly individuals who feel alone and who are willing to speak openly about it. Their feelings of loneliness are abundant and varied. For some, they’re closely tied to widowhood, to missing someone who was at their side for many years and who is no longer present. Some come to us after a long period immersed in caring for others, often a spouse. There are also widows who don’t associate their loneliness with the loss of a spouse, because they’ve accepted this loss or even because it has freed them from an oppressive relationship. Some feel lonely even when living with family. They associate this with a lack of communication with others, because their children have no time for them or have no interest in the issues that concern them. They explain that they receive support when they need it, but they feel abandoned in their daily lives. Some have spoken of situations that make loneliness even worse: the economic recession or the urban environment. The recession has caused many children and grandchildren to move in with elderly parents, invading their space and saddling them with an additional economic burden, often without providing adequate company or respectful coexistence. Some define the urban environment as hostile, especially those from rural areas who have been unable to establish a network beyond their family, even after living in Barcelona for many years.

Possible evolution of the phenomenon

It’s often said that loneliness is on the rise, and that it will continue to increase. This is a complex issue and we don’t yet have the data to confirm it. If this phenomenon is associated with aging and aging is increasing exponentially all around the world, it makes sense to say that there will be more and more elderly people and, as a result, more and more lonely people. However, we’re also aging better, with greater quality of life and autonomy, and as a result perhaps a smaller proportion of elderly people will suffer loneliness in the future.

We should also refer to two additional, conflicting theories. On the one hand, some authors believe that the evolution of societies that are increasingly individualistic will make all of us more Scandinavian. In other words, we’ll become more independent, with greater personal resources, greater emotional education and fewer expectations for others and, as a result, we won’t feel as lonely. On the other hand, sociologist Zygmunt Bauman, who also accepts the idea that society is increasingly individualistic, ascribes a very different set of consequences to this trend. Bauman claims that we’re losing our community. He states that loneliness is our greatest fear in this individualistic age. The social networks our new technologies provide us with serve as a false substitute for community. Our feeling of control over these networks, where we can add and remove individuals at will, makes us believe that we’re less alone. Nevertheless, we’re losing the true social abilities required by daily interactions, such as interacting with those who think differently, or knowing how to coexist with controversy. Networks pen us up in comfort zones where we can only hear the echo of our own voices. They’re useful and pleasant tools, but they’re also a trap.

Loneliness increases our risk of suffering from mental and physical illnesses, and it increases mortality and the use of social and health resources, including homes for the elderly; this is a well-studied and established fact. The effects of loneliness can be compared with tobacco or a lack of physical exercise. In addition, loneliness often coexists with symptoms of depression, anxiety and sleep problems, and with the treatment of the same using psychiatric drugs. We still don’t know how many of these treatments are strictly necessary, and to what degree psychosocial interactions could prevent them from being necessary. Are we medicating loneliness, widowhood, a lack of communication? We have plenty of evidence that many of the people that visit health centres suffer from emotional problems related to life processes that need to be addressed globally, and that community resources can be of great use. The social prescription programs currently promoted by the Catalan Health Service and the Department of Health of the Government of Catalonia are based on this idea.

Playing billiards at the Espai de Gent Gran Sant Antoni (Sant Antoni Space for the Elderly), in Càndida Pérez gardens, in the Sant Antoni neighbourhood. Studies show that by forming groups of friends among the elderly and promoting joint activities, we can improve quality of life and reduce mortality and the use of medical resources.

Photo: Vicente Zambrano

Social prescription is a term that has received a great deal of criticism because of both the “prescription” and the “social” aspects. Equivalent to “asset recommendation” or “derivation to the community”, it’s a tool that allows health professionals to suggest nonclinical local and community services to improve the health and welfare of individuals. It’s meant to avoid treating emotional problems such as loneliness with drugs. To the same end, the Barcelona City Hall has prepared an internet-accessible map of city assets, and it has a long history defending initiatives and organizations that promote social support and emotional welfare for individuals. These programs are part of the notable resurgence in community healthcare from medical centres. In these processes, healthcare teams provide local diagnosis of needs in a participative way, and the loneliness of the elderly is one of the needs that’s most often identified and prioritized. Nevertheless, loneliness isn’t an illness, and any medical intervention must be careful not to medicalize this human condition.

Dealing with loneliness on a social and individual level

Loneliness must be addressed on both a social and an individual level. The most methodologically rigorous study on reducing this problem was prepared in Finland (Pitkälä, 2010). It involved the creation of groups of friends among lonely, elderly individuals with shared interests, and the organization of joint activities. As a result, there was an increase in quality of life and a reduction in mortality and the use of medical resources. The results were also positive from a cost-effective point of view. As a result, this model was applied throughout Finland.

At the UAB’s Health and Aging Foundation, we applied a program inspired in the Finnish model but adapted to our environment (L. Coll-Planas, 2017). On a local level, we promoted support programs and social participation programs for individuals suffering from loneliness. We obtained varied results. Some women made friends for the first time and no longer felt lonely; others simply reduced their feelings of loneliness. Loneliness attributed to widowhood proved difficult to reduce, although participating women did feel better in other aspects. Subjects also told us that, thanks to our intervention, their neighbourhood now seemed friendlier; the individuals that had met would gather, say hello to one another or inquire about each other’s health. Overall, they told us that they felt “life was worth living” again.

Loneliness is all around us, in our society, our neighbourhoods, our apartment blocks and in our individual lives… What do we want to do about it?

References

1 – Dykstra, P. A. “Older adult loneliness: myths and realities”. Eur J Ageing. 2009; 6 (2): 91-100, doi: 10.1007/s, 10433-009-0110-3.

2 – Sundström, G.; Fransson, E.; Malmberg, B.; Davey A. “Loneliness among older Europeans”. Eur J Ageing. 2009; 6 (4): 267-275, doi: 10.1007/s, 10433-009-0134-8.

3 – Pitkälä, K. H.; Routasalo, P.; Kautiainen, H.; Tilvis R. S. “Effects of psychosocial group rehabilitation on health, use of health care services, and mortality of older persons suffering from loneliness: a randomized, controlled trial”. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009; 64 (7): 792-800, doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp011.

4 – Doctoral thesis in Public Health from the UAB. “Solitud, suport social i participació de les persones grans des d’una perspectiva de la salut.” Laura Coll-Planas, May 2017.

5 – Bauman, Z.; Donskis, L. Moral Blindness: The Loss of Sensitivity in Liquid Modernity. Wiley, April 2013.