Historical narratives from the time of Spain’s Transition to Democracy have sometimes ignored the role of social movements and particularly the importance of women in residents’ and workers’ movements. The four life stories we present exemplify how women activists are marginalised because they belong to the working class, they are women and, in some cases, they are migrants.

A demonstration by the cleaning staff of the Hospital de Bellvitge, organized by the trade union Comisiones Obreras, to demand improvements to working conditions; Via Laietana, 1986.

Photo: Lluís Salom

Paqui Jiménez played a prominent role in one of the landmark workers’ struggles of the final period of the Franco regime: the Harry Walker strike. Maruja Ruiz, chairperson of the La Prosperitat Casal de la Gent Gran (a day-care centre for older persons), was one of the organisers of a lock-in by women and children at the church of Sant Andreu de Palomar, in 1976, in solidarity with their husbands and fathers, who were on strike at the Motor Ibérica factory. Llum Ventura is a councillor for the district of Ciutat Vella and one of the founders of the association Les Dones del 36 (The women of 1936), which has worked to commemorate the women of the Spanish Civil War. Hotel chambermaids, one of the most ignored and badly treated labour collectives of our time, are represented through the testimony of Rosmery.

“Willy, we’re being followed”, I said to Willy, although in reality that wasn’t his name.

“Don’t wind me up, Ana”, he must have replied, though that wasn’t my real name either.

It was 1970 and our bus was travelling along Virrei Amat. A few days previously, the women who worked at the Harry Walker factory had gone on strike. I was one of them. I had collected the addresses of all my striking workmates and I was so scared that the papers with their addresses on would be found that I decided to hide them in my knickers, wrapped in plastic and fabric, like a sanitary pad.

“Ana, we’re being followed.” Willy became so nervous he got off the bus and left me on my own. We all have moments of panic and by then the police had already arrested one or two of our colleagues. And they had hurt them quite badly. So I stayed on the bus until the very last stop, in Trinitat Vella, and then I ran and I ran, seeking refuge at the home of some priests who were friends of mine.

“Do what you like, but I’m sleeping here tonight”, I said, and so I did. I was so scared when I got off that bus on Via Júlia: the bloke who was following me nearly caught me, but I ran and I ran.

Paqui Jiménez, who played a leading role in one of the landmark strikes of the final years of the Franco regime, at the Harry Walker automotive factory, 1971.

Photo: Albert Armengol

Ana’s real name is Paqui Jiménez and she was born in Baeza (Jaén) in 1946. For decades now she’s been living in a small flat in L’Esquerra de l’Eixample, where she’s recalling those times in a calm, clear voice, surrounded by countless house plants.

One street away from Via Júlia lies the Casal de la Gent Gran (a day-care centre for older persons) for the La Prosperitat neighbourhood. Maruja Ruiz, its chairperson, was born in Guadix, Granada, in 1936. She is a veteran community activist. I ask her how many times she had ended up in police custody. “Well, kid… Many times, I can’t even remember, but I was always released… The day we protested about the bogus building on Via Favència we were put in a cell with two blokes who were suffering from withdrawal symptoms. A neighbour was with me, and he was scared out of his wits because he’d been arrested; he was crying and everything. One of the junkies was banging his head against the wall and shouting… That neighbour who was with me must still be around here, I think… I never heard any more from him!” Maruja, with her sky blue eyeshadow, hair perfectly backcombed, laughs at the memory.

Llum Ventura is a councillor for the district of Ciutat Vella and was born in Poble-Sec, Barcelona, in 1941. “I was born into a family of anarchists: always on the losing side, but very committed. I had a tough childhood; I was almost entirely ignored as a little girl. But one day a relative of ours who ran a hairdressing salon in the neighbourhood started calling on me to help her wash hair. Later, I set up my own salon in my flat, on the seventh floor.”

Llum Ventura, a district councillor for Ciutat Vella and one of the instigators of the project to preserve the historical memory of the role of women during the Spanish Republic and Civil War, through the Les Dones del 36 association.

Photo: Albert Armengol

In 1979, in a new but fragile democracy, Llum Ventura opened another salon called La Mar, right near the Picasso Museum. It was a small space with a little library for the women of the neighbourhood, with not a single gossip magazine, and Llum offered information on how to get an abortion: “Once a month, Françoise, a woman from Toulouse, would come to perform clandestine abortions.”

Rosmery’s fingernails are very pointy, like those of all the hotel’s chambermaids. Apparently, the constant contact with fabric, sheets and towels makes your nails as sharp as knives. If you get distracted and they rub against your skin you’d cut yourself, and you can’t let that happen. Rosmery’s boss runs a tourist apartment and gives her just half an hour to clean it from top to bottom. She doesn’t even have time to complain: “In high season, we might not even have one day off. We hardly get to see our own families; we get home just in time to have dinner and go to bed and up again the next day to go to work”, she pushes up her glasses and takes a much-needed moment’s pause. “It’s like slavery: we don’t have a life.” Rosmery has had to stop working because she suffers from epicondylitis (an injury more commonly known as tennis elbow), but she has barely two months of unemployment benefit remaining. If it were not for the help of the Las Kellys chambermaids’ association, Rosmery would be left completely defenceless. Her injury has not even been recognised as a work-related condition.

Multiplied marginalisation

The historical narrative of Spain’s Transition to democracy, according to historian Cristina Borderías, has for a long time ignored the role of social activism and, even more, the historical significance of women as regards community-based and workers’ struggles. The life stories of these four women are just a small sample of an enormous, perverse reality; that of the double (and even triple) marginalisation of working women, of spirited women. The official narrative has locked them out of its memory because they belong to the working class, they are women and they are migrants.

The fingernails of the women working in the Catalan textile industry must have been as sharp as those of today’s chambermaids. “The Industrial Revolution happened in Barcelona because of women”, says the historian Isabel Segura. After the introduction of the steam engine, factories began to modernise and the whole structure of Barcelona changed. In modern homes, kitchens had only one door and space for only person: a woman, of course. Domestic work was unpaid and the husband’s wage was not enough to feed the family. The woman would have to work in the home and in the factory. For example, in the mid 19th century, a woman living in Sants would patch up her family’s tattered clothes and not charge for it, but she would also get up at five in the morning to go to work at the Güell, Ramis y Cia textile factory – the Vapor Vell, the largest textile factory in Spain at that time – and she would weave and weave for twelve hours for a meagre wage, even less than what a man would earn for doing the same job.

The factory was in operation from 1846 to 1890 and three-quarters of its employees were women. Its proprietor, Joan Güell (Torredembarra, 1800) got rich in Cuba, where he monopolised the entire textile market of Havana. There are unconfirmed suspicions that part of his fortune came from the slave trade. It’s no surprise that activist groups in Sants, which were behind the conversion of this and other old factories in the neighbourhood into public amenities, have covered over the street name of Carrer de Joan Güell, on the wall of the factory, and replaced it with Carrer de les Dones del Vapor Vell (Women of the Vapor Vell). The struggle to turn the spotlight away from the upper classes to the working classes in the historical narratives on the construction of Barcelona often starts with a comprehensive and egalitarian review of street names.

It has never been easy for women to balance their two working lives (domestic and paid employment) with an active role in social movements. As well as the obvious problem of having the time, many male factory workers did not like the idea of working alongside women. They felt that the job was being degraded by the fact that a woman was doing it and that this led to lower wages, explains Nadia Varo, a historian: “These things were happening right when jobs were in short supply. There were attempts to expel them from the employment market, they were prevented from working as apprentices and there was never any question that their wages should be much lower.”

Historically, women were also not helped by the opinions of some of the socialist and anarchist intellectuals of the second half of the 19th century. The ideas of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, one of the fathers of anarchist ideology, were nothing short of cruel. Proudhon saw the home and domestic work as a woman’s natural place. It’s worth saying that this was not the general view of revolutionary thinkers and that Friedrich Engels, for example, put forward much more acceptable ideas in his book The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State: “The emancipation of woman will only be possible when woman can take part in production on a large, social scale, and domestic work no longer claims anything but an insignificant amount of her time.”

A large demonstration through the centre of Barcelona, demanding an amnesty for the women, 1977.

Photo: Pilar Aymerich

According to data collected by Isabel Segura and presented in her book Dones de Sants-Montjuïc, itineraris històrics (Women of Sants-Montjuïc: historical itineraries), in 1905 Barcelona’s textile industry as a whole employed over 5,000 men, almost 16,500 women and just over 5,000 children in poor working conditions and with working hours that often did not even comply with the labour laws in force since 1873, when the working day was set as eleven hours a day. The year 1905 was also the year that textile worker and anarchist Teresa Claramunt (Sabadell, 1862) published La mujer. Consideraciones generales sobre su estado ante las prerrogativas del hombre (Women. General thoughts on their condition in the face of the prerogatives of men), one of the groundbreaking texts of feminist anarcho-syndicalism in Spain. Previously, Claremunt had, in 1889, set up Spain’s first feminist organisation, the Autonomous Women’s Society of Barcelona (SAMB). Arrested as a result of the attacks on the Corpus Christi procession of 1896, Claramunt went into exile in England until 1898, although she was never officially convicted of any crime. In 1902 she took part in the February general strike and was again arrested during Tragic Week ( a week of violent clashes between the Spanish army and the working classes), which occurred in Barcelona in 1909. Teresa Claramunt died on the eve of the 1931 municipal elections and was buried on 14 April 1931, the same day that the Second Spanish Republic was proclaimed.

“Liberate married women from the workshop”

The Spanish Civil War and Franco’s dictatorship halted any signs of women’s progress, emancipation or liberty. Franco’s labour laws, the Fuero del Trabajo, were passed in 1938 and promised to “liberate married women from the workshop and factory”. Marriage was declared to be “once only and indissoluble”, according to another of the basic laws that underpinned the dictatorship, the Fuero de los Españoles (1945). Abortion and disseminating contraceptive practices became a criminal offence in 1941, and maternity was seen as a biological and Christian duty, as put forward by Pilar Primo de Rivera, head of the women’s section of the Falange political party from 1937 to 1977: “Women’s real duty to the Nation is to form families with a solid foundation of austerity and joy, families in which they foster all that is traditional.” And if women wanted to work, they needed their husband’s permission.

Despite this, the battered economy of the post-Civil War period could not afford for millions of women to not work – the textile industry was one of several that had collapsed – and, as such, plans to “liberate women from the workshop” were to fall by the wayside. These were years of silent struggle, years that district councillor Llum Ventura remembers as “the time of hush, hush, don’t talk about that”.

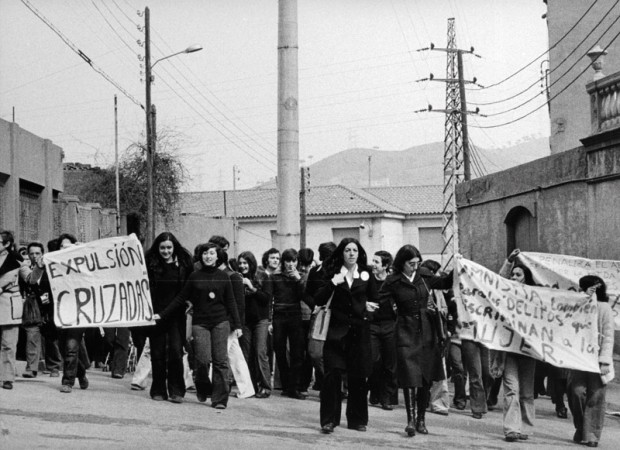

Demonstration outside La Trinitat women’s prison to demand that the nuns, of the order of Cruzadas Evangélicas de Cristo Rey, who were in charge of the prisoners, be replaced by professional prison guards; that prisoners be allowed to read legal texts, speak in their own language and wear their own clothes; along with other demands. 1976.

Photo: Pilar Aymerich

It’s not the first time that Ventura has worked for the local authority. Sipping on her cortado coffee, one can see the nostalgia in her eyes as she recalls her time as an independent councillor under Pasqual Maragall: “I was much further to the left, but I accepted the position so I could work on projects like commemorating the women of the Spanish Civil War, known as Les dones del 36 [the women of 1936]”. She travelled to Madrid, asking for names. In Barcelona, she visited women who were members of the Communist party, the Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC) and the Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification (POUM), but she was particularly keen to make contact with an anarchist woman, as her mother and aunt had been (also called Llum). “I had to tell the people in the CGT [the anarcho-syndicalist trade union, the General Confederation of Labour] that my name was Llum and that my mother’s was Llibertat, and that the commemoration project could not go ahead without a female anarchist.” So it was that she met Concha Pérez, a libertarian and anarchist who had been held for several months at the women’s prison on Calle de la Reina Amàlia: “It was through that project and, in particular, through meeting Concha, that I returned to my libertarian roots and values.” The “hush, hush” was over.

Memories don’t last if they are not passed on. Ventura and the women of ’36 set up an association and went into primary and secondary schools, keeping the memories alive and passing them on to the younger generations. They gave a talk on Montjuïc for the twentieth anniversary of the first Catalan Women’s Conference, held at the University of Barcelona in 1976.

Women in movement(s)

To commemorate the fortieth anniversary of that conference, the City Council set up a project called “En moviment[s]. Dones de Barcelona. 40 anys i més… 1976-2016” (In Movement(s). Women of Barcelona. 40 years and more… 1976-2016). The project will continue until July and it includes exhibitions, panel discussions, events at Cinefórum and the publication of a text written by historian Cristina Borderías, the project commissioner: “The project came about because we have a local government that is more open to these issues and because, in recent years, we have seen a growth in the feminist movement. The initiative has been well-received by feminist groups, which is not always the case with projects launched by the authorities. There is a stronger connection now between the feminist movement and the city administration”, says Borderías.

The pro-democracy and anti-Franco activism of the women of that time remains solid, even if the memory of what they did has been left to one side. “Women had a presence in trade unions, political parties and community associations, but they were denied access to management roles and not given any representation in these organisations”, Borderías explains in the book written for the “En Moviment[s]” exhibition. It was this commitment that drove Paqui Jiménez and her colleagues at the Harry Walker automotive company to go on strike during the dictatorship, at a time when such action was completely illegal.

What was it like to work in that factory? Paqui Jiménez explains in detail: “The carburettors would come and, using these hard, fine blades, we would remove the burrs. There were almost twenty of us women working on a production line. It was really tough: when I went to the toilet, my legs would buckle from the effort I’d had to put in. If we didn’t earn the productivity bonus, the wage was just not enough. We’d work from 6.00 in the morning until 2.00 in the afternoon, with 18 minutes for a mid-morning snack. The men had very basic jobs, they’d work on the shift and get splashed with this kind of oil that burned your hands. The bosses would put the most strong-minded women there. I’d protest. I didn’t want to go there.” Paqui grimaces, bites her tongue but finally opens up. “I’d curse the boss and he’d refuse. He was this illiterate bloke, a loser, a lout who treated woman like pigs… I would stand up to him, I scared him and in the end he would take me off the shift.”

During the dictatorship, the masculinisation of women was a constant, says Nadia Varo, a historian specialising in the role of women in the workers’ struggles organised by the Workers’ Commissions (CC.OO.) at that time. “Women were victimised when they suffered as a result of the working conditions, but when they took a strong role in an actual conflict they were masculinised and seen as male workers.” This was done out of fear that the male workers would not accept women as comrades in arms.

“They kept on increasing the amount of work we had to do to get the bonus”, recalls Paqui Jiménez, “and we just couldn’t do it, it was impossible. People were really wound up. The management threatened to sack some particularly militant colleagues and it was then, in 1971, that we set up the Harry Walker’s workers committee and went on strike. We’d meet in secret. I remember getting up at three in the morning to go and throw leaflets down into the entrance of the Santa Eulàlia metro station. It was all very quick, we’d throw them down and run off to get to work at the factory for 6 am. That way, if anything happened, I could always say that I had gone to work.”

Maruja Ruiz, one of the women who organized the protest by the wives of Motor Ibérica workers, now Chairperson of the Casal de la Gent Gran de la Prosperitat, a day centre for the elderly.

Photo: Albert Armengol

Historian Cristina Borderías explains that it was through the workers’ struggle that many women discovered “the limitations of individual action and the need to mutually support each other”. Paqui Jiménez is more explicit and recalls that when she got into those circles “her eyes were opened as big as saucers”. For Maruja Ruiz, community activism also means solidarity, unity and cooperation: “You have no idea how much one has to lose!”, Maruja scolds the youth of today. “I get goosebumps just thinking about you having to go through what we did… Goosebumps!”

The sit-in at Motor Ibérica

“My husband spent thirteen years working at the Motor Ibérica plant [which produced vehicles and machinery] and they fired him for leading a strike. It was 1976, the same year people were asking for the labour amnesty. So I spoke at the neighbourhood assembly and said that I could mobilise the wives of the workers”, says Maruja Ruiz, exuding self-confidence. “We tried to get them to take notice, but there was no way, so in the end we decided to stage a sit-in.” To mobilise the women, Maruja went to the Vertical Syndicate, the only trade union allowed in Franco’s Spain. “I went to the union and I told the men that we’d have an assembly with the women. I called the women. When I had the group set up, quite a nice group, we decided to lock ourselves in (the women and the children). We looked for somewhere central, the church of Sant Andreu de Palomar. What’s now the town hall of the Sant Andreu district, opposite the church, was then a health centre, and we thought it would be a good thing to have it so close just in case one of the kid’s got ill. And the metro was just a short way away, and the Pegaso, Maquinista and Fabra i Coats factories were also really close by. So it was easy for people to follow the sit-in.”

In June 1976, a large group of wives of workers at the Motor Ibérica factory, staged a sit-in at the church of Sant Andreu de Palomar together with their children, in a show of support for the strike their husbands were holding. They were forcibly removed by the police after 28 days.

Photo: Pilar Aymerich

When Maruja Ruiz gets going, it’s impossible to stop the flow of memories. “The priest, name of Camps, was very wary because the CNT people [the anarcho-syndicalist trade union, the National Labour Confederation] had also locked themselves in there at one point and had left the place like a pigsty. I promised him that we would fix anything that we broke. So we got in. I brought a stove and some milk, not much, because I thought we’d get thrown out the day after. No-one imagined that we’d last 28 days.” More than 250 women and children took part. “We’d block the door with statues of saints to stop the police coming in at night.” But, in the end, come in they did.

“We knew that something was cooking when they opened up the factory and the bastard strikebreakers went back to work”, explains Maruja. She eyes the audio recorder, hesitates for a moment and finally says: “Bah, it doesn’t matter anymore if anyone knows”, and continues her story. “When the police came, we started tolling the bells to summon people and the square filled with people who came to stop the eviction. I told my workmates that we should wear our Motor Ibérica jackets with nothing underneath. I had been fined by Motor Ibérica for wearing their work clothes without being a member of staff, so I guessed that the police would tell us to remove our jackets. There was one of us, Julia, who had boobs like melons… when the police came through the courtyard at three in the afternoon, breaking everything in their path, they shouted: ‘Remove your jackets!’ But when they saw those boobs they changed their minds and shouted ‘Put on your jackets!’”

At this point Maruja Ruiz cannot contain her laughter and loses track of the story. That’s how she talks, in fragments and going off on tangents. “I’ve got everything ready for Carnival. Can you imagine fifty-odd eighty-year-old grannies dressed as rats? With little tails and everything… we’re going on the neighbourhood parade.” Maruja descends the stairs of the day-care centre nimbly and purposefully. She rests her hand on the bannister, but she has no need of the support.

“We spent seventeen years fighting to get this day-care centre. They were going to put up a block of flats on this site, and we would dismantle the crane every night. I think Josep Porcioles was the mayor at the time…” Dates and names get a little mixed up in her head, but she doesn’t mind, because she’s more interested in the stories than the figures. “When Jordi Pujol [the then President of the Catalan Regional Government] came to open the day centre, I told him he was seventeen years late.”

The historian Isabel Segura explains that “there is no division between the neighbourhood association movement and the feminist movement, because the feminist movement was directly involved in the demands for improvements to the neighbourhood. If, for example, there was a shortage of school places, it would be a couple of mums, fed up of travelling miles every day, who would decide to take action”. Women organised themselves into networks: that’s why they were not so boxed into solid structures, Segura recalls. “When conflict arose, the women created a network, other activists joined them and in the end it would end up being the men who were the public face of the demonstrations.”

The enemy within

Despite this, too often the women who have taken part in social movements in Barcelona have found the enemy within their own ranks. “At the time, society was much more chauvinistic than it is now, and the people who took part in these actions were also very sexist. They were part of society and they reproduced its models”, explains Nadia Varo. Not all of them truly defended an equal society, even if they were good at paying lip service to it.

Paqui Jiménez remembers that, during the Harry Walker strike, she twice went to sleep at a flat in Besòs. “We all slept on the floor, and there was one guy who’d move in on me and touch me. ‘Hey, please don’t touch me’, I protested. And he’d answer: ‘Paqui, you’re frigid. If you want to be a fighter for workers’ rights you have to be sexually liberated.’ And I’d say: ‘I’ll liberate myself when and with whom I want. But don’t think you can come and grope me in the middle of the night, because I’m not having it. And if that’s being frigid, then that’s what I am and that’s the end of it.’”

The living room is pervaded by the smell of the stew she cooked a little while ago. The former Harry Walker employee seems sad when she remembers these situations. “Chauvinism has always existed, and when you had to suffer it up-close, it seemed like there was no other option but to just lump it…” If these things happened between colleagues, one can only imagine the behaviour of the police under General Franco. She explains how “they called you a whore, they called you everything under the sun, and said that you should be at home cleaning…”

It was a learning experience for Paqui Jiménez. “I learned about the unity of the working class, the sense of working class pride. Really important ideas that people don’t think about nowadays. Working-class consciousness gave me the strength to carry on. There was great camaraderie in the factory, although there were one or two scabs too… Once, one of them got five kilos of paint thrown over her head: I felt bad about that, I really did”, the sad look on her face is clear. “I wouldn’t have been able to do that, but at the time, deep down, you felt like she deserved it, that she was asking for it… And anyway, she was as thick as two short planks stuck together, she just didn’t get it.”

Being a working woman changed her too. “I discovered what it meant to be a woman in that society. I learned that you can say no, that we had the same rights as anyone else, and that if we women stood together, we could win. Oh, yes! And I discovered financial independence. Because my family was poor, I gave all my wages to my mum and I could see that if I wanted to leave home, I couldn’t depend on a man. That was the biggest liberation I’ve felt in my life. You men, especially when you’re young, can’t even imagine what that feels like.”

It wasn’t easy for Maruja Ruiz: “Because I was always hither and thither, surrounded by men all day, some people thought I was a prostitute and that’s what they told me when I brought male colleagues to a clandestine meeting for the first time.” One of the workers at Motor Ibérica tried to make his wife leave the sit-in, but she refused. “She had seen what solidarity meant and she cried as she told us that she was not leaving.” She didn’t leave, and her husband reported her to the police for abandoning their children, then he took them away. The story has a happy ending, or maybe a predictable one: he ended up giving the children back to his wife because they were too much work.

A group on the margins

Rosmery only has two months of unemployment benefit left and she worries about how she will feed her children in the future. Isabel Cruz, a member of the Las Kellys chambermaids’ organisation, points to outsourcing services as one of the biggest problems that apartment chambermaids have to face. “The fact that they are not on the hotel’s payroll, but on that of a subcontracted company, means lower wages, excessive workloads and reduced workers’ rights.”

Chambermaids, marginalised because they are working class, female and, often, migrants, have very few resources to improve their working conditions. “They suffer a lot of stress, and because they are scared to ask for sick leave, they end up self-medicating”, explains Isabel Cruz. Prozac and ibuprofen to treat the impossibility of resting as they should or of having the family life they deserve. “There are cases of chambermaids who, at eight months pregnant, are spending their days making beds and moving mattresses.”

“Barcelona is an all-year tourist destination. How is it possible that all these chambermaids have temporary or zero-hours contracts? The only explanation is that the business owner knows full well that the worker will end up getting ill because of the working conditions she’s subjected to”, says Isabel Cruz. “In our association we have several cases of workers who have been sacked for taking sick leave, or chambermaids on zero-hours contracts who are told on one day not to come back for the next: these dismissals cost very little for business owners”, she explains.

The social movements of the Transition period fought for a more just and equal city. But on the margins of society, where we find the Las Kellys workers, there is not a trace of justice or equality.