The worst of Huertas’ time in prison was the first month. The first five days of isolation were full of questions, followed shortly thereafter by the statement from ETA member Wilson, so damaging to him.

Josep Maria Huertas was halfway through his imprisonment when Franco died on 20 November 1975. The fact that he did not say one word about it in the first letter he sent afterwards, dated 23 November, or in any subsequent letter, is quite telling of the atmosphere of intensified control over the prisoners that existed. Surprisingly, not all the explanations I gave him in the letters that I sent around that time were censored.

During the five months that passed between Franco’s death and Huertas’ release, his letters revealed a constant cycle of ups and downs, of optimism and pessimism. On 12 October he wrote: “I only have three strengths to fight against the scepticism and despair that have surrounded and besieged me: being a Christian (who knows why); believing that what I was writing (not everything, of course) served a specific population; and an old phrase from Vázquez Montalbán, from an article in [the magazine] Triunfo, entitled ‘The journalists’. I was more or less saying that we were subjected to all manner of grief and enjoyed only one grace, that of regaining our own dignity day by day.” On 3 December he quoted Stavros, the main character in the film The Anatolian Smile by Elia Kazan, when he is intimidated and demeaned: “No one will be able to stop me from maintaining a shred of dignity in the innermost part of me.” That December it was looking like he was going to be home in time for Christmas, but the holidays came and went, as did four more months, and he was still in his cell. On 10 December he wrote: “I’m in good spirits today. I hope it lasts! Maybe it’s getting the notes, maybe it’s still discovering little details about our monumental project, maybe it’s finding out that my son’s talking now, maybe it’s knowing that there are more of us every day…” His son Guillem turned two on 31 January, and in the nine months in prison Huertas had only been able to see him once, on Christmas Eve.

On 4 January: “I’m still living in hope here, which is getting pushed back from week to week.” And ten days later: “Although fairer winds are blowing on my anchored boat, I’m getting tired.” And the next week: “I’ve just been given a big dose of that bit of realism I’ve been living off for a long time…” On 15 February: “There are certain good impressions about my case, but faithful to my principles I’m maintaining my militant pessimism.” Sometimes, the possibility of an amnesty he might benefit from peeks through in the letters; however, he did not get this amnesty, with all its drawbacks and restrictions, until 15 October 1977, when he was already free. And so the weeks continued to pass and, although “hope has another tone” (14 March), he never gave up what he called realism or that which made him eschew false hopes and impatience and continue on with his activities in the prison. It was the best way for him to pass the time quickly and not get engrossed in the Kafkaesque situation of the final weeks, with the doubts over whether the case that had been moved to the Public Order Court would go back to the military court. Although on 11 April, two days before getting out, he wrote: “I had wanted this to be a happy letter. But luck and I have been divorced for some time… Things are fairly complicated for the time being.” But the nightmare was about to end.

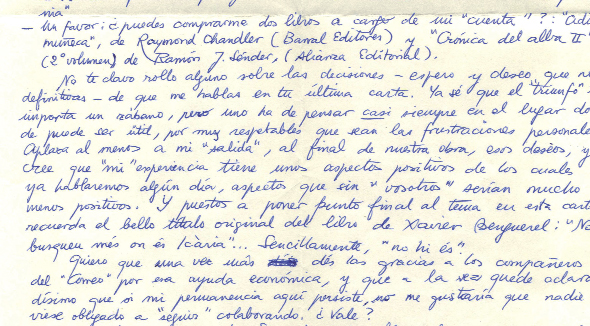

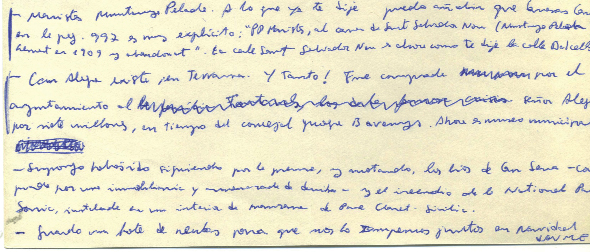

For eight months, Josep Maria Huertas and Jaume Fabre exchanged correspondence regularly, in order to continue working on Tots els barris de Barcelona. They also spoke of their moods and events inside and outside of prison. Above, a letter by Fabre.

Archive: Jaume Fabre.

The letters were censored, but I never got any with parts blacked out and none ever failed to reach me. The same can be said about the ones I sent him. As journalists who were used to working under the dictatorship, we knew the limits well and we knew how to write between the lines. That is why there are a good number of references to outside events linked to the political situation, which increased after the death of Franco and the months of Arias Navarro’s government.

Of the pieces of information that reached him, thanks to the correspondence and the newspapers (with bits cut out due to the censorship) that were allowed in, the two that interested him most were the elections in the Press Association in November, which were for the first time won by a democratic body, and the announcement of the launch of the newspaper Avui, which he followed with extraordinary interest from prison, and which he asked me to subscribe to on his behalf. On 7 April, one week before getting out, he wrote: “I hope that this difficult adventure of the first Catalan newspaper since the end of the Civil War has as good an outcome as possible, and that they don’t aspire to be the newspaper of all Catalans, because such a thing can’t exist, or if it did it would end up being La Vanguardia or La Llanterna from [Joan Puig i Ferreter’s novel] Servitud. I suggest – although no one is asking me for suggestions or advice – that it should be for all Catalans who have had it up to here with journalistic drivel, with the saying that God brings glory to those who speak Catalan, with [Barcelona’s Mayor Joaquim] Viola, with cliques and with so many other things.”

The relaxation of censorship was demonstrated by the fact that on 1 February he was able to write the following without any problems: “Parcels arrived yesterday from Joaquim Boix Lluch, the same one for whom one hundred-odd priests – when they used to wear cassocks – protested on 11 May, ten years ago now. I thought of doing a story about the event.” And he actually did it, because by May he was already back on the outside.

The matter about Joaquim Boix’s parcels warrants clarification, though, which is explained in the letter I sent him on 3 February, in response to his: “On Saturday night I was on call at the newspaper and Boix showed up to explain to me that he had got the parcels thanks to the Secours Populaire Français [French Popular Relief], whose representatives held a press conference before leaving Barcelona, which I wrote about in El Correo [Catalán].” During Franco’s lifetime, such things could not have been put in a letter to a prisoner or published in the press.

From punishment cell to library

On 20 October 1975 there was a riot at La Model brought about by the death of a common criminal known as “El Habichuela”, due to abuse. That meant that the cells in block five (used for common and political prisoners considered dangerous), which were normally occupied by just one prisoner, were set up as punishment cells, with three prisoners in each one. The regime was a 24-hour lockup. All meals were eaten in the same shared cell, one corner of which was home to a toilet bowl, which was not separated in any way.

This indirectly benefited Huertas, because from the end of October, it meant he was no longer alone and had the company of Quico Bofill (the ex-monk from Montserrat who had sent the Basque separatist Wilson to his house) and of Jordi Roca (also linked to the case). Although the company created annoyances, solitude was even worse. On 29 October he wrote: “The darkest hours have passed. There are three of us in the cell now, and the days are more pleasant, less agonising. Maybe that’s why they say ‘misery loves company’.”

The only entertainment for the prisoners in the punishment cells was whatever they themselves could come up with – like creating a secret game of chess with breadcrumbs – or the books that Josep Maria handed out each day, passing through with a trolley accompanied by a trustworthy prisoner. In principle lending books to prisoners in the punishment cells was not allowed, so being able to do this was a small victory achieved after incessantly begging “Master José”, who was in charge of the library. In the other blocks, the prisoners who were not confined to punishment cells were able to go read in the library, which Huertas looked after during the day with the “master” having the primary responsibility, or they were able to do the other activities permitted in the prison: going out in the yard, studying, working.

In a letter dated 16 September, Josep Maria told me, “I’m a library assistant; in other words, I have a position and a job, but it still doesn’t count towards my freedom (in other words, they don’t give me 3 days for every 2 that I spend here)”. In practice he ran the library, provided books to the prisoners and enriched the collection by bringing things in from outside. He sent me endless lists of books he considered of interest to the prison, which I had to request from the publishers. The lengths I went to in order to get them resulted in all kinds of anecdotes.

Huertas had a real obsession with making up the volumes that were missing from works that had more than one volume, and I darted around to find them in antiquarian booksellers’, at a time when you couldn’t even dream of using the internet to find rarities. There were difficulties in getting some books in and some were lost along the way, maybe due to censorship, maybe just because the ones they said they had sent they really had not. The meanness of some infuriated him: “Someday,” he wrote on 10 December, “I will remind them that I don’t want to see them with a desire to read in a place whose name I don’t want to remember.”

He describes his work timetable in detail in the letter from 28 January: “I have a ‘life plan’, but as you can imagine I didn’t have that much say in preparing it: only in terms of spending the mornings (from 8 to 10 and 12:30 to 1:30) on writing the book, except Thursdays, when I do my weekly Catalan class. I also spend some time on the book in the afternoon, and then there’s the library, which takes up a lot of my time. The rest you can pretty much imagine: military style, but without leave.”