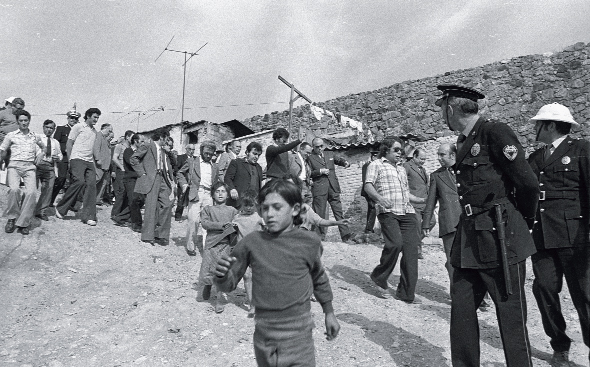

Huertas leaving prison on 13 April 1976.

Photo: Pepe Encinas / Europa Press.

The rest of the photos are from the archives of Huertas family and Jaume Fabre.

For eight months, the author maintained regular correspondence with Huertas, imprisoned in La Model, which documented both Huertas’ state of mind as well as events in and outside the prison. The two also exchanged information related to the books about the districts that they had begun to write jointly.

On 22 July 1975, Josep Maria Huertas was called before the Military Government of Barcelona, where a military judge issued an indictment against him for the newspaper report “Vida erótica subterránea” (“Underground erotic life”) that had been published in Tele/eXpres on 7 June. He was sent directly to La Model prison in handcuffs and put in cell block two. The next day, five of the city’s newspapers failed to hit the streets as the employees went on strike in solidarity with him.

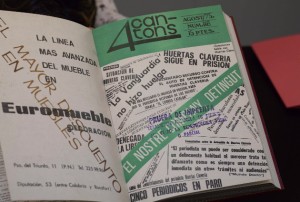

The article that resulted in a martial court, included in the official volume of the sentence. Photos: Huertas family and Jaume Fabre arxives.

The report contained two lines saying that in the 1950s, widows of soldiers found it easier to obtain a permit to run meublés (rooms couples could hire to engage in sexual relations) than other people did. The publication of this information bothered the military establishment, who decided to teach the journalist a lesson and, in passing, to intimidate the entire profession.

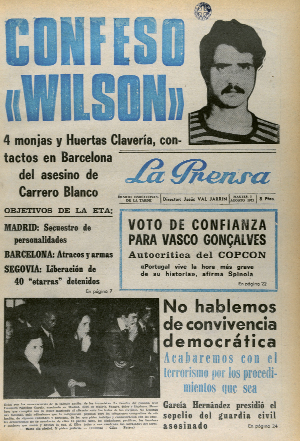

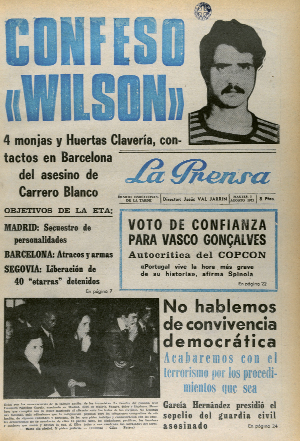

The Francoist newspaper La Prensa accused Huertas of being connected to ETA member Iñaki Pérez Beotegi, Wilson, considered one of the brains behind the assassination of Carrero Blanco, head of the Spanish government.

At first, Huertas’ situation in the prison remained “under a regime of relative tolerance of movement”, as he himself later described it. That ended on 5 August, however, when the Falangist newspaper La Prensa ran the front page headline: “[ETA member] Wilson confesses. Four nuns and Huertas Clavería – the Barcelona contacts of Carrero Blanco’s killer”. A second indictment was handed down, and Huertas was put in solitary confinement in cell block five, where dangerous inmates were held.

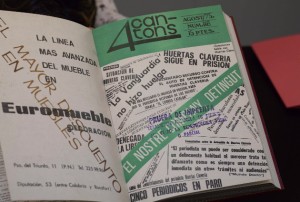

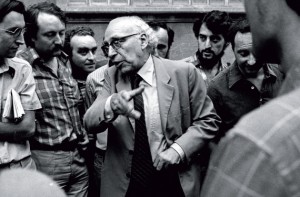

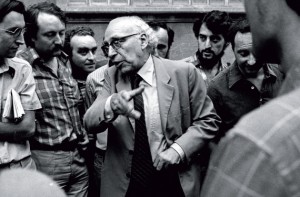

A collection of news on the case in a facsimile of the magazine 4 Cantons. This edition was never distributed, and almost all copies were destroyed. On the previous page, Huertas met by a group of journalists outside la Model, on 13 April 1976.

Two members of the Basque separatist group ETA, Iñaki “Wilson” Pérez Beotegi and Juan “Txiki” Paredes Manot, had been imprisoned there not long before. Wilson carried a diary that had Huertas’ name in it, as well as the name of an ex-monk from Montserrat, Francesc Bofill, who was also arrested and sent to La Model. The reason those two names were in Wilson’s diary was that Bofill had helped him find temporary accommodation in Catalonia, and Huertas had hosted him for a few hours at his house, at Bofill’s request. Huertas had not known exactly who he was, and directed him to his parish, in Poblenou. That is why the rector Joan Soler was also detained for a few days.

On 24 August 1975, Huertas was court-martialled for the report in Tele/eXpres and sentenced to two years in prison, which he served at La Model during the time the trial for the Wilson case was being processed.

Death of Franco and mobilisation of the press

On 25 July 1975, three days after Huertas was imprisoned, journalists Andreu-Avel·lí Artís, Sempronio and Maria Favà tried to visit him in representation of round fifty professionals who rallied outside of la Model in solidarity with their imprisoned colleague. The prison director received them, but did not authorize them to visit Huertas.

On 20 November 1975, Franco died. Nine days later the pardon granted by King Juan Carlos meant the first case against Huertas was dropped, although he had to remain in provisional custody due to the Wilson case. This would take almost five months to be resolved, however.

The jurisdiction of the military authority was declined in the second trial on 11 March in favour of the Public Order Court. An issue of jurisdiction was then raised, which delayed the granting of provisional release and left open the possibility of the criminal investigation going back to the military court. The intervention of the Minister of Justice Garrigues Walker prevented this, and the case continued in the Public Order Court, which granted a provisional release on 12 April, one month after the first authorised demonstration by journalists had taken place in Barcelona. Placards at the demonstration called for freedom of expression and the end of Huertas’ imprisonment.

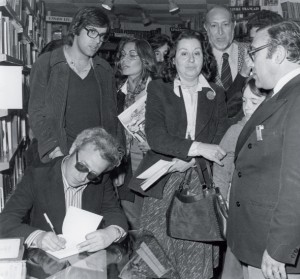

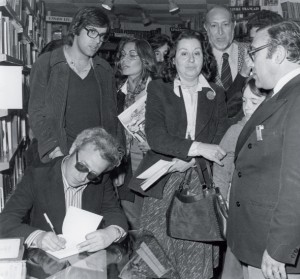

A few days later on Sant Jordi, Huertas signing copies of Tots els barris de Barcelona.

Josep Maria Huertas left La Model in the late evening of 13 April 1976, Easter Monday. On 22 April, he attended the party to present the first issue of the newspaper Avui. He spent the next day – El dia de Sant Jordi (St George’s day, in honour of the patron of Catalonia and a day when men traditionally receive books as gifts) – visiting bookshops and signing copies of the first two volumes of Tots els barris de Barcelona [Every District in Barcelona].

A very strict prison regime

In prison, Huertas got a position as a library assistant and did a second-level course in Catalan via correspondence. What kept him busiest, however, was continuing to write Tots els barris de Barcelona, three volumes of which we had already delivered to the publisher. We had finished one section of the fourth volume and still had two districts to go, El Coll and El Carmel. There were still three volumes left to finish in the series, one of which (the fifth overall) was written entirely by Huertas from prison.

It is important to note here that we are talking about a Spanish prison at the end of the Franco era, prior to the reinstatement of freedoms and the 1978 Constitution, which existed under a regime that operated much differently from the present-day system.Interviews with lawyers took place from behind bars, without the possibility of exchanging any objects, and all correspondence and anything else delivered to prisoners was subject to checks and censoring. Prisoners could not receive any visitors other than immediate family members and lawyers, and they could not send letters to anyone other than immediate family or a single person previously designated by the prisoner. Huertas decided that I would be that person for him, so that we could continue working on the books about the districts. Our correspondence was authorised, but the express and formal permission to work on writing the book (without a typewriter, of course) did not arrive until mid-November. This situation caused problems which included not being able to get Huertas material such as galley proofs, books, photocopies, notes or photos.

The regular correspondence thus began with his letter from 30 August and my first reply from 2 September, which were followed by 58 more back and forth. This was 32 weeks before 11 April, meaning there were around two letters a week. Their value, therefore, lies in the fact that they are the only letters Huertas was able to write in prison and send to the outside, other than those of a very different nature that he sent to his wife and his son. There were very few of these letters as he spoke to Araceli every day since she was acting as his lawyer, and his son was just a year old. All the letters had to be written in Spanish.

I always sent my letters in a yellow envelope to post box number 20. The censor complained about my handwriting to Huertas on several occasions and demanded that I improve it, without any success. Except for one letter, I always wrote them by hand, in principle to preserve the warmth of the handwriting and avoid the coldness of the typewriter.

He sent his letters in a white envelope, and in microscopic handwriting, because they only let him write on one side of one sheet of letter size paper, twice a week. “Your writing will soon look like Espriu’s”, I told him, referring to the famous Catalan poet, in my only typewritten letter dated 11 October.

Writing between the lines

Regarding the content of the letters, there were two clear phases. The first, up to 20 November 1975, was marked by great restraint in terms of commenting on the book project, words of encouragement or intimate expressions about his mood. In this phase, we had to put to the test all the skills of writing between the lines that we had acquired over years of practising journalism under the 1964 press law. One example is this sentence with a double meaning, written on 2 November, apparently referring to work on the book, but loaded with another meaning, after the dictator’s long death throes had already begun: “Let’s see when we can get rid of this dead stuff!” But from 20 November onwards, we started to express ourselves with fewer restrictions and, although aware of the still oppressive situation, we could include references to specific facts about outside life or the general political situation without any problems. This more flexible censorship broadened as the weeks passed by.

Before Huertas’ imprisonment, we had divided up the districts that each of us had to write about in a way that enabled us to work fairly autonomously, yet with a constant exchange of information and opinions, and with each of us doing a final review of the other’s text. When he was arrested, the first three volumes had already been finished and delivered to the publisher, while the fourth was halfway done. The work done over those 20 months consisted of writing about the two districts that were missing from the fourth volume, as well as the entire fifth volume (by Josep Maria) and the entire sixth volume and part of the seventh (by me). The collated galley proofs of his texts for volumes 1, 2 and 3 were also corrected. The first two volumes finally came off the press on 9 April. We then took them to the prison, but Josep Maria did not end up getting to see them. In early December we had also brought him a copy of the second edition of his biography of the Catalan anarcho-syndicalist Salvador Seguí, known as El noi del sucre (“the sugar boy”, in Catalan).

The prison made it necessary to establish a work system that was very different to the one we had been following for the volumes that had already been finished, because Josep Maria had completely lost his autonomy and it was necessary to provide him with most of the material he needed to write his part. He found a gold mine in the prison library, where, to our surprise, there were some very interesting books about the history of Barcelona, including Recuerdos de mi larga vida [Memoirs of my long life] by Conrad Roure, and the highly significant work about the city by Francesc Carreras Candi published in the Geografia General de Catalunya [General Geography of Catalonia] (1908–1918).

In his letters, Huertas constantly expressed his admiration for the work of Carreras Candi. “I’m reading nearly the whole thing, and once again I’m convinced (we’re convinced) that it’s the best book about the city of Barcelona that there is.” He devoured it from cover to cover in prison, and that was one of the things that most helped him to stay active: “Today or tomorrow,” he wrote on 22 October, “I will have finished all of Carreras Candi’s book, which is very much a feat that, believe me, I am doing more through an act of sheer will than through desire. The only desire I have now is to rest. I don’t know when or how. Sorry, it’s a bleak day, and my health is weak.”

Long-distance research

Besides the books from the prison library, Huertas only had his elephantine memory and his previous knowledge of the districts he was writing about. The rest we had to look for on the outside and give to him via official channels. First of all, we had to search his house together with his wife Araceli for the notes and press clippings he had there. I gave him everything I could from his files and from what the press was publishing, as well as the books he asked for. During this stage, one of the tasks that took up most of my time was the documentary research work in the newspaper libraries at the Casa de l’Ardiaca archives and the National Library of Catalonia, a task made difficult due to the poor management of these institutions at that time and a strike by officials that kept me from gaining access.

Then there was the fact that I had to continue to maintain personal contacts to collect information that he was unable to obtain. That meant interviews, correspondence, roundtables with residents’ associations and other business. In that regard, it is worth mentioning two opposite sides of the same coin: those people who, out of laziness, never responded to our request for information, and those who acted out of a sense of solidarity beyond all measure. A list of each type of person would bring surprises. Those who most distanced themselves were individuals who would later assume prominent positions in municipal politics, while those who most helped us were friends whose names would not mean anything to anyone today. Another significant bit of information: some people who would not lift a finger later appeared in the media saying that their involvement was key.

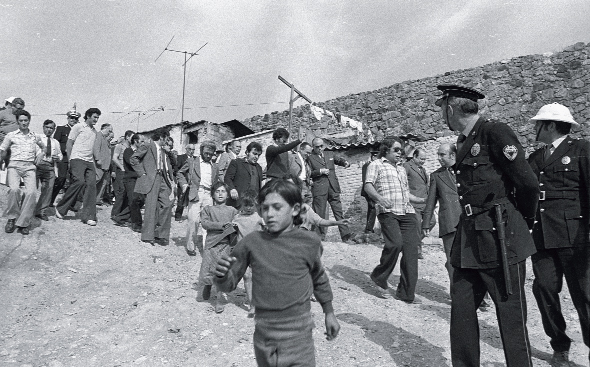

Josep Maria Huertas (centre, with a beard, briefcase and light-coloured pants) at a visit by Mayor Masó (further right, with dark glasses, a suit and tie) to a shanty town in Barcelona.

Apart from collecting information so that Huertas could write his part, on the outside there were many other tasks: looking for photos – Pepe Encinas gave his full cooperation here until he had to leave for military service – as well as creating maps and the fact sheets that accompany the districts in their respective volumes and, finally, keeping in touch with the publisher and the Bofill Foundation, who had given us a grant in 1975. And, obviously, I had to write my part (the estates in volumes six and seven) and meet my work commitments at El Correo Catalán, the newspaper that was my source of living income, and the managers of which tolerated my lack of full commitment without any complaint.

We gave the texts that had already been drafted to a typist who we cannot say was amongst the most supportive people at the time. On 23 January I wrote to Josep Maria: “The typist conned me in a bad way. Do you know how much she charged me for El Coll and El Carmel? At first I’d accepted 50 pesetas per page but she did it with big margins and spaces and on letter-size sheets instead of A4 sheets. What’s more, she charged me separately for the paper. In short, a big rip-off and a real shock to our already sufficiently tortured finances.” Another obstacle was that I was admitted to a clinic for fairly delicate surgery in the second half of December and the first fortnight in January.

The most significant support came from Araceli and included taking and getting material, searching for material in her house and typing up short texts. Pepe Encinas helped a lot with looking for photos in the negative folders that Huertas had left in his house. He made contact prints from the negatives that we would take to the prison and also had full-size prints made. In addition, he took photos that Josep Maria told him to. Several people provided information about the districts; one of the greatest contributors in this regard, according to the letters, was Miquel Villagrasa, who was very familiar with the Sant Pere district.

Defining the concept of a ‘district’

In addition to the questions and responses about specific issues, the letters also reflect our disagreements about what should and what should not have been considered a district. It must be borne in mind that we are talking about 1975, when what would later be the official map of Barcelona’s districts had not yet been defined, or even sketched. We started from a clear outline provided by the former municipalities and historical districts of old Barcelona. But many new problems arose because of recently built estates, border areas and because of the divisions created by the large ring roads, such as Ronda del Mig, Ronda de Dalt and Ronda del Litoral, which were beginning to take shape then. Although we had made an outline of the work before starting, doubts began arising as we were working on it about whether to consider certain areas we had not taken into account as districts. This was especially due to the fact that, as we were writing, new residents’ associations were being formed in areas that had not had any particular sense of identity up to that point.

Next to the houses on the left of the image, Josep M. Huertas at the Cases Barates (‘cheap houses’) in Bon Pastor, one of the four neighbourhoods built in 1929 to house the immigrant families who arrived in Barcelona, drawn by the city’s Industrial expansion.

The fifth volume (which included the Eixample and Barcelona Vella areas) – the one written in full by Huertas in prison – should, in theory, have raised few issues of definition. It raised other substantial issues, however, referring in particular to a more appropriate vision and a new focus that would avoid the clichés commonly found in historical books or doctoral theses that some pedantic person might want to publish. “For 30 years I’ve lived close to El Ninot,” he wrote to me on 19 October, “and that’s as much of a district as I am an Egyptian mummy. It is a market, and there was probably a time when its surroundings were classified that way. But I again emphasise that, if we don’t want to create a sort of Enciclopedia Espasa (traditional Spanish encyclopaedia) then our guiding principle has to be the present; in other words, within the Eixample we should consider as districts the areas that are ‘alive’, or that possibly have a residents’ association, with however many subdivisions they want.”

This contemporary focus which places an emphasis on residents’ movements and the popular demands of the second half of the 1960s and first half of the 1970s is what gives the books a distinct character. And 40 years on, when an extensive bibliography about Barcelona’s districts exists, this quality also ensures that they will retain their value as records of a key moment in the history of Barcelona. However, having made conversations with people one of the books’ most fundamental aspects also makes them valuable from another standpoint: they contain many hitherto unpublished findings that have been stored in the city’s collective memory and become part of the anonymous cumulative body of knowledge whose creators no one bothers to wonder about.

To learn more

–Huertas, J.M., Morell, S., Roma, H. i Sales, F.: La presó: quatre morts, vuit mesos i vint dies. El cas Huertas Clavería [Prison: four deaths, eight months and twenty days. The Huertas Clavería case]. Preface by Agustí de Semir. Editorial Laia, Les Eines collection, 36. Barcelona, April 1978.

–Huertas, Josep M.: Cada taula, un Vietnam [Each desk, a Vietnam]. Edicions de La Magrana, Meridiana collection, 22. Barcelona, May 1997. (pp. 71–96).

–Caballero, J.J.: El cas Huertas, quaranta anys de la primera batalla per la llibertat d’expressió [The Huertas case, 40 years since the first battle for freedom of expression].

–Cap de turc, bandera de llibertat: Josep Maria Huertas [Scapegoat, flag of freedom: Josep Maria Huertas]. Virtual exhibition on the website of the Association of Catalan Journalists].