Magazines produced in New York are a window onto the cosmopolitan world that North-American laws and customs seek to express. Barcelona’s presence in The New Yorker began in 1935, with a description of the Carnival which foreshadows Post-Civil War morality, clashing abruptly with the joie de vivre of the Second Republic, still in power at that time.

© Pérez de Rozas / AFB

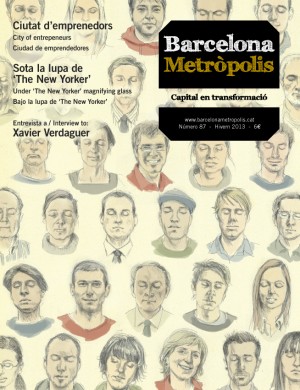

The first references to Barcelona are published in ‘The New Yorker’ in an article about carnival in 1935. The carnival image is from the following year: the burial of the carnival effigy in the Jardinets de Gràcia.

Founded in 1925 with the aim of becoming a satirical and erudite weekly, The New Yorker immediately sold well. It faithfully represents the step-sister-like relationship between the United States’ cultural capital and its hinterland: they love each other through their blood ties. It often seems that they would have to maintain an incestuous relationship, but they keep their distance, one that is born of resentment.

Magazines made in New York are a window onto the cosmopolitan world that North-American laws and customs seek to express, and constitute a powerful incentive for young artists who dream of finding a place on the literary Olympus of the Anglo-American language and of art in general. Journalism is an instrument of power; it explains, with total transparency, the debts that each writer has with their country and the price they pay for the place they hold in the concert of nations. Thus, 20thcentury American magazines are akin to cultural aircraft carriers. Boom-boom, large calibre.

The New Yorker weekly magazine is associated with old-style, deliberate journalism, with long articles. Ten or twenty pages that keep up appearances, written to make language and conversations its own, meticulously documented: always flush with anecdotes and good taste. It is the capital of literary reporting, and it pays well. You look at a powerful city, which leads an upstanding country, and immediately you see its cultural wealth and a breed of creators who have time to write and the room to take risks.

The sadness of a Carnival

If you enter the word “Barcelona” in the search engine of The New Yorker’s archive, you get 223 hits. Since 1925, 4,100 issues of the magazine have been published, which means that Barcelona appears once in every twenty, or twice a year. However, this is the average, since during Franco’s dictatorship there are a meagre ten mentions. The first reference to the city is a brief article from 1935, in the “Talk of the Town” section, namely the cocktail of curiosities that purportedly occupy local chinwags. It is entitled “How Sad”, and reproduces a letter by a citizen of Barcelona who had lived in New York, describing a parade of carnival floats along Passeig de Gràcia. And it ends:

“In the streets hundreds of people dressed almost exclusively as ‘Charlots’ or ‘Gandis’ walk and try to persuade themselves that they’re having a grand time […] Strongly armed mounted police reminded everybody of the drastic prohibitions, as are the ones forbidding the use of masks and throwing any streamers with colours that would offend the morals, the political feelings, and the ‘religious’. I hurried on my way to the American Bar.”

The image is a clairvoyant one: citizens of Barcelona dressed up as Charlie Chaplin’s The Tramp and Gandhi, or in other words as clowns or pacifists (or as anti-fascists or pro-independents, which sounds better), surrounded by armed patrols. Five months have elapsed since 6 October and the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War is a year and a half away. What colour does a streamer have to be to offend political feelings? The reaction of the chronicler, who heads straight for the American Bar, is also premonitory: hedonism as a way out of grief, cocktail cosmopolitanism as asceticism. It foreshadows the post-war morality and clashes with the joie de vivre and mythical agitation of the Republic, still in power.

The other articles focusing on Barcelona are by paid reporters. One in 1944, two from the 1950s and two from the 1960s. After Spain’s transition to democracy, articles multiplied and became both more varied and specific in terms of topics: particularly painting, dancing, architecture, and more recently gastronomy and Woody Allen. There is one from 1992 which, leveraging the Olympic Games, takes a look at Catalan nationalism with some almost microscopic details but which comes up somewhat short as an overview. This, plus the five articles published about Barcelona during the dictatorship, explains the phases the city has been through, and its relationship with the country, as well as the sins we have yet to atone for.

Carai, sr. Graupera. sempre llegint, estudiant, recopilant, o amb plena foscor, fent llum a RAC.1 Quines piles uses?.

Pingback: Barcelona, sota la lupa de The New Yorker | Núvol