More than half of humanity now lives in cities. Now that we’ve passed this key milestone in the global process that is turning the rural population into an urban one, it’s a good time to stop and think on the possibilities for life and coexistence in the major population centres. This was the idea behind the series of lectures organised in Barcelona in November, under the title “Ciutats (+) Humanes”.

There is growing concern for the future of life in our cities. One can feel it in the corridors of global power: the enormous sense of expectation created by summits such as Habitat III last October in Quito, when the top mayors discussed the sustainable development of urban life; or when the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development included a specific goal for cities (number 11): “Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable.” And we can see it in people’s day-to-day lives: in cities like Barcelona, L’Hospitalet and Badalona, dozens of talks have been organised from the bottom-up, on refuge cities, the impact of tourism, networks of cities for sustainability, mobility and health, turning water services back into public companies, and much more.

Why is the future of cities such a central topic for social and political debate? A few numbers will allow us to understand the magnitude of what we’re dealing with: at the beginning of the 20th century, of every ten people, only one lived in a city; in the middle of the century, it was not quite three out of ten, and today it is over half of humanity. It is predicted that by 2050, almost 70% of the world’s population will be living in urban areas. In Spain, this figure is already 80%. The world’s cities only occupy 3% of the Earth’s surface, but they consume between 60 and 80% of the energy and produce 75% of all carbon emissions. We are facing an unstoppable process.

The increasing population density and sprawl of our cities began with the Industrial Revolution. London, at the end of the 19th century, was the first city to surpass the five million mark in terms of population. Today, the most populated cities are in Asia and Latin America, and most of them have well over ten million inhabitants. In the West, cities are just starting to recover after the biggest economic crisis of the last thirty years, but as they do so, they are showing major inequalities in their population and wounds that have not yet healed. The cities of the global South have seen disorganised and uncontrolled growth over the last few years and their urban planning needs a major rethink.

We are standing right on the threshold between an eminently rural society and an urban one, so it is here, on this borderline, that we need to stop and think on the possibilities for life and co-existence in cities. This was the idea behind the series of lectures held in November by Cristianisme i Justícia, the Joan Maragall Foundation, the Carta per la Pau (Charter for Peace) Foundation, the magazine Valors and Barcelona’s Movement of Catholic Professionals.

We believe that there are three key factors for co-existence in cities: identity, cohesion and sustainability. Is it possible to build more humane cities? How do we take on today’s urban challenges by focusing the debate on people?

In this issue of Barcelona Metròpolis we pick up the topics that were discussed by the various speakers at these lectures, as summarised by the authors themselves. This article may serve as a general introduction.

Building citizenship

Civitas is the Latin term that refers to relationships and participation in cities, an aspect that is guaranteed by civil rights. There is no city without citizens, without active life, without engagement and without the creation of active subjects. Cities were born in the Middle Ages precisely as a refuge from the domination and subjugation of feudal lords, as a way of finding that space of anonymity that allowed for freedom and the weaving of a social fabric in which security and creativity were possible.

But this citizenship cannot be taken for granted. Citizens and non-citizens live side-by-side in cities. Some learning is required before one can exercise citizenship: we need to acquire skills for dialogue, to let every voice be heard, to allow the silent majorities to blossom…, these are key challenges for the megalopolises that no longer have just one colour, one face, but that are becoming multicultural, multi-ethnic and multi-faith.

Another key aspect for building a community is trust: what happens in cities when lots of people arrive from elsewhere? How do the circles of trust and the interactions between neighbours change? The conclusions are not particularly positive: there are no interactions between the long-term, rooted residents and the new-comers. Many people say that certain degrees of integration are impossible to attain and that cultural diversity generates mistrust, which leads to the tortoise shell effect, when people stop relating even to the people they used to relate to.

So we need processes that can transform the urban reality from the grass roots, to build real communities and not cities that have been divided up into sealed compartments. As the Basque sociologist Imanol Zubero says, we may all be sleeping in roughly the same area but that doesn’t mean that this place has to be reduced to the status of a hotel or “dormitory city”, just as the places where we work and produce don’t have to turn into mere “business districts”, the spaces in which we consume don’t have to be “hypermarkets”, and our leisure activities don’t only need to be conducted in “theme parks”. Whether the city is a space for business and consumption or a space for interaction and coexistence will depend solely on how we answer the question of the meaning of the city.

Again in the words of Imanol Zubero, cities are models of organised complexity. It is diversity that builds cities as living, balanced realities, while the absence of this organised diversity gives them a death blow. So we need to distinguish, as Manuel Delgado does, between public space and urban space: the former regulates what has to happen, while the latter is the city that reaches its full potential.

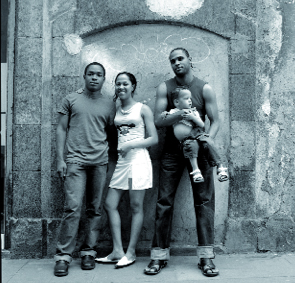

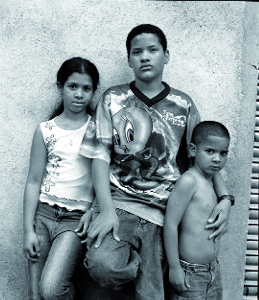

Image from Joan Tomàs’s Mi barrio (My neighbourhood) project, an installation with 140 portraits of people from the Sant Pere, Santa Caterina i la Ribera neighbourhood. This and the rest of the photos in this article could be seen in Plaça de Sant Pere in 2004 and 2009. Since February 2015, they have been part of a permanent exhibition called Qui som? (Who are we?), located in the passageway that connects Carrer del Pou de la Figuera with Carrer dels Carders.

Photo: Joan Tomàs

The dangers of a non-cohesive city

The city as a polis relates to the space it provides for governance and decision-making. But democracy in the city is not possible when inequality simply grows and grows. In a city like Barcelona, life expectancy at birth is ten years more in Pedralbes than in Ciutat Meridiana, neighbourhoods that are separated by just ten kilometres of ring road. Is it really possible to have democratic participation, to exercise political rights and to find cohesion in such polarised societies?

Greek democracy, born in the polis, is the paradigm but it was actually a democracy of the elite, of the free men. Today, if we are to achieve true democracy, we need to guarantee not just the political freedom but the material freedom of citizens.

Participation is both a right and a source of rights. But we know how difficult it is to participate in decision-making in cities. Today, there are so many dividing lines – abyssal lines – as the Coïmbra sociologist and professor Boaventura de Sousa Santos would say, separating those who have rights from those who cannot even aspire to them; those who are part of the decision-making processes from those who count for nothing. The future of the city, and therefore of the polis, is only decided from one side of the abyss.

In a truly cohesive city, housing should not be a reason for exclusion and expulsion. There are a number of fallacies that are bandied about, like the one that says that social housing is for the poor when in fact a large majority of the population needs housing support. We don’t all need to own a house; we need to change the prevailing ownership system to offer rental housing and to make the rental system easier to use.

To guarantee cohesion, we need to consider, as well as a suitable housing policy, a whole range of measures such as a minimum wage that is matched to the actual cost of living, or participatory budgets that allocate funds to meet the real concerns of residents. A city that offers equal opportunities and access to decision-making leads to good integration. All these are elements that make up the desired “right to the city”, in Lefebvre’s words.

Here in Spain, the new councils of the so-called “cities of change”, like Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia and A Coruña, are bringing new opportunities and interesting challenges in the areas of community participation, transparency and the rethinking of what is “public” in the city, challenges that are obviously not exempt of ambiguity and that can potentially lend themselves to mistakes.

The sustainability angle

If we want a city that works for life, and is not merely functional, it is essential that we think about its structure, how its spaces are designed, its fabric. The sustainable city is continuous, compact and densely populated, unlike the plans that are often implemented. This type of city uses less energy and land and fosters relationships between people.

It is also the city that has spaces for interpersonal relationships, like community centres, children’s nurseries, parks and gardens. Ultimately, it has spaces for contact, spaces which, as Marina Garcés points out, make it possible to have a communal life, as opposed to the tendency to create a sectioned-off life.

Many urban planners advocate housing policy as the spearhead of any city planning project. Sustainable is also synonymous with inclusive. We need the city to be designed so that it facilitates learning for communal life. Today, we are seeing a serious breakdown of family and social structures, and to fight this we need education about our habitat, learning on how to live in a community. Neighbourhoods are the right level at which to practice and internalise this learning process. In this way the city will be built by everyone and everyone will use its spaces.

Even Pope Francis, in his latest encyclical, which took a clearly environmentalist approach, says: “The feeling of asphyxiation brought on by densely populated residential areas is countered if close and warm relationships develop, if communities are created, if the limitations of the environment are compensated for in the interior of each person who feels held within a network of solidarity and belonging. In this way, any place can turn from being a hell on earth into the setting for a dignified life” (Laudato si’, no. 148).

The Barcelona paradigm

The rapid growth of Barcelona in the late 19th century was driven by two social movements working in parallel: the enlightened Barcelona that was entrepreneurial, rich, modern, well-to-do and of a liberal mindset, and the working-class Barcelona, with its anarchist and republican tendencies, but also with a strong entrepreneurial spirit.

After the grey era of dictatorship, the city performed a second tour de force in the run-up to the Olympic Games of 1992. This was when the city opened up to the sea; the shanty towns of Barceloneta, Somorrostro and Montjuïc were demolished; the city’s symbols were internationalised and the famous “Barcelona brand” was created, as was the model for success that it shows to the world today. It was this success that the city wanted to repeat in 2004 with the highly questionable Universal Forum of Cultures. Once again, there were two Barcelonas in opposition: that of technological innovation and the 22@ district, facing the more underground movement of social activism and antiglobalisation, of libertarians and Catalan separatists, etc.

In a small but truly cosmopolitan city, where a multitude of cultures live together, with a 17% immigrant population, we now find ourselves facing two major challenges. Firstly, how to overcome the tensions created by the inequality between neighbourhoods: the richest areas have average incomes that are six times higher than those of the poorest districts. This is a polarised city that has been driving out the immigrant and low-income population and that has created little ghettos inside itself or in the greater metropolitan area. The second major challenge is how to slow down the untrammelled tourism and the predominance of economic interests. The number of tourists who came through Barcelona in 2015 was 7 million, with 17 million overnight stays. The tourism sector makes up 15% of the economy and does not stop growing, which means that the job market and the economy are highly seasonal, there are problems for neighbours and a high degree of gentrification, which is the big challenge for successful cities, both now and in the future. We may end up turning our cities into lifeless cardboard cut-out backdrops. There are too many economic interests in exploiting the Barcelona brand.

Both of these challenges are repeated across all major cities. Despite a few attempts at reform, all city councils, whichever way they lean, are always tripped up by the same stone: the real impossibility of making any decisions on issues affecting the life of their citizens. In part, the debate on the closure of foreigners’ reception centres has to do with the inability of councils to impose regulations on a space created for the deprivation of liberty within its own municipal borders. One solution would be to give councils more regulatory capacity and more ability to self-manage resources. But the inability to regulate on many areas of life gets even worse when steps are taken to recentralise powers, such as the recent law on local authorities.

A new agenda for the future of the city

In these new global cities that are the driving force of the world economy, the mix of cultures makes them representative of the plurality of the whole world. They are flagships that are spearheading the changes we will see: some people, like the New York political theorist Benjamin Barber, even say that mayors could end up ruling the world. If that is the case, we need to reflect in depth about how to put the goal of a dignified life at the centre of their development.

What would we want this reflection to take into account? At least this: the need to put life and care for life right at the centre of the city, rather than success and economic growth; to highlight its human richness, with the contribution of young and old, rich and poor, able-bodied people and those with disabilities, men and women, natives of the country and immigrants, etc.; to use the assets provided by nature fairly and sustainably; to unite the rural world and the urban world, emphasising the origins of everything that makes life possible; to create opportunities for everyone to participate and be involved in decision-making as we build a collective life, without having to depend on the government and institutions; and to create the security conditions for a life without violence and without fear, especially for women.

All these factors, and undoubtedly many more, lie at the heart of our ability to build cities that are a little more humane.