Faced with a sense of unease at how globalisation is scraping away at the nation state, many people (even politicians from opposite ends of the spectrum) are once again looking to the city as a last hope for creativity, solidarity and identity-building.

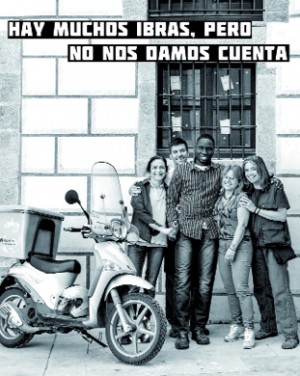

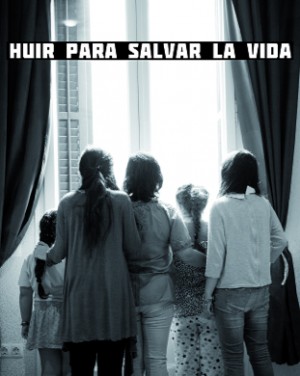

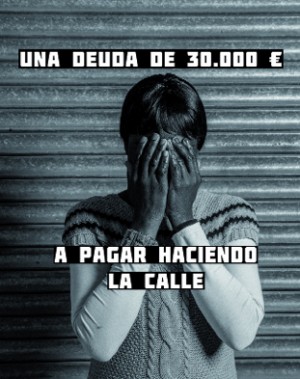

In this article are various images from the photography project Diálogos invisibles, vidas sin derechos (Invisible conversations, lives without rights), by the photographer Joan Tomàs and the Mescladís Foundation, which were printed on the roller shutters of Barcelona businesses in 2015. The photos recalled the accounts of immigrant people and their families.

Photo: Joan Tomàs / Fundació Mescladís

Next to neoliberalism, the city looks like a centre of competition and innovation, with a particularly strong role given to what are known as the “creative classes”, including immigrants, as key components of “diversity”. Thus, the process of attracting talent has now become part of cities’ brandification (and governance), stamped with the seal of “cosmopolitanism” and “cross-culturalism” that so trivialises diversity. Against this background, it’s worth emphasising values like proximity, relationship density and defence of the common good and shared assets, from the understanding that the intercultural space par excellence can be none other than the one that is built on the participation of city-dwellers (and of the different communities that inhabit the neighbourhood) through processes of social innovation.

The real city, and its image, must therefore be the product not so much (or not only) of competition but of this fight for social justice. It is these struggles that forge new identities, speeding up the sense of belonging in concentric circles from the closest sphere of daily life – the neighbourhood. At least this was the model put forward by Francesc Candel for immigration in the 1960s.

There are also those who protest against all the overexcitement bubbling around the paradigm of “citizenism” as a new and appeasing ideology imprisoned in the fetishist view of public space as a space for negotiation owned by liberal democracies.

Historically, the city has expressed itself as a product and as a spatial representation of both utopia and dystopia, and it involves the construction of residents’ identity as citizens, based on their participation in the affairs of the polis. In a context of deregulation, today’s tensions are expressed in terms of the possibility of becoming rooted not in cultural difference, but in the utopia of ‘mixophilia’ (in praise of the melting pot) or the dystopia of ‘mixophobia’, based on the fear of losing identity.

Hypermigration, the city and identity

The threat of a fragmented identity and weaker solidarity that may lie in hypermigration does not completely conceal the fear of disorder inspired by the banlieue. Time and time again, the fear of urban violence transforms social feverishness into ethnocultural confrontation and serves as an excuse for ever tighter security. This fear manifests itself in the obsession of stigmatising areas with highly concentrated and segregated social groups (the two concepts are often confused), labelling them as ‘ghettos’, which leads to a fall in the housing market. This confusion also ignores the fact that the highest levels of segregation (voluntary in this case) occur among the upper classes.

It’s not these processes in themselves that should worry us, but how they develop into the pigeon-holing that is associated with poverty and social exclusion. This pigeon-holing tends to define (and recreate) identities in an essentialist way, taking only the ethnicity of the individuals in a community (starting with the women) and refusing to acknowledge the obvious plurality and fluidity of identity inherent to citizens of the 21st century. And that is the case both for newcomers and for natives.

When we talk about the conflict between newcomers and natives, as expressed in the Catalan saying “de fora vingueren i de casa ens tragueren” (roughly translatable as “they came from abroad and pushed us out of our homes”), we are referring to what some have called the social (and demographic) reproduction crisis, caused by the tension created by accelerated flows and deterritorialisation that happen on a global scale but are manifested on a local level.

Barcelona, for example

In the 21st century, Barcelona has seen a migration boom – from 2000 to 2015 more than a million foreigners arrived from other countries and from other parts of Catalonia and Spain – and this has not only led to a permanent change in the city’s human landscape (in 2015 there were 353,000 inhabitants who were born abroad, 22% of the total, and in neighbourhoods such as El Raval this was as high as 56%); it also forces us to redefine the identity of the city and of its inhabitants. The search for a shared concept of citizenship has used interculturalism as its hegemonic discourse, emphasising the concept of firstly, ‘putting down roots’ and secondly, participation.

When it comes to origins, the diversity is obvious: more than 180 countries are represented here and of all the people born abroad and living in one of Barcelona’s 73 neighbourhoods, 13 different countries of origin hold first position: Ecuador (20 neighbourhoods), Peru (14), Argentina (14), Pakistan (5), Morocco (4), Italy (3), France (3), the Philippines (2), China (2), Bolivia (1), Colombia (1), USA (1) and Russia (1).

Territorial identity is strongly liked to how long people have lived here and their expectations. Many of the social coexistence issues that are seen as ethnocultural confrontation have an element of generational culture-clash, relating to the sense of belonging to a neighbourhood, which must not be brushed aside by class prejudice. These differences are accompanied by an unequal rootedness that, when measured in years of having lived in Barcelona, looks like this: more than half of registered foreigners came here five years ago or less (a ratio that in some neighbourhoods goes up to 70%), while 60% of Spanish-born residents have lived here for over thirty years (a percentage that exceeds 80% in some neighbourhoods). Alongside this, we need to consider the newcomers that are still provisional because they consider their stay here as part of a sequential and transitory phase in their migration.

In the coming fifteen years, the structural momentum – along with an ageing population – will also mean that young people in Catalonia will be identified by the diversity of their origins. In the city of Barcelona, 11% of all people under the age of 18 were born abroad, but if we add those that were born in Spain to foreign-born parents, the number increases to over half of this section of the population (the 2011 census already estimated that it was 32.6%). Regardless of their parents’ migration plans, today’s children (be they native or immigrant) – the young adults of tomorrow – may see the metropolitan area as one of their primary points of reference in terms of identity, along with other national, transnational or deterritorialised reference points.

Blade Runner or…

The so-called ‘postmetropolises’ like Barcelona have been identified with the dystopian landscape of Blade Runner, made up of surplus, unrooted humans and technological debris, where cosmopolitanism is a sham for integration.

To stop the city from becoming a banal backdrop for the enjoyment of tourists and the economic system from reducing its inhabitants to the condition of surplus population by dispossessing them of the shared assets, we need to build new paths, complex and multiple identities that include conflict as well as the ownership and creation of spaces shared by all citizens.