Through his books and blog, Seth Godin has inspired thousands of entrepreneurs all over the world. He is the founder of Squidoo.com, which is ranked among the United States’ one hundred most-visited websites. Godin has defined, better than anyone else, the new business and socialisation models currently being established in the new “connection economy” following the emergence of social networks and information technologies, and has successfully communicated this in books and conferences, workshops and blogs that have had a global resonance. Our thanks to Seth Godin for allowing us to publish six of his reflections on the future of entrepreneurs.

1. The forever recession (and the coming revolution)

There are actually two recessions. The first is the cyclical one, the one that inevitably comes and then inevitably goes. There’s plenty of evidence that intervention can shorten it, and also indications that overdoing a response to it is a waste or even harmful.

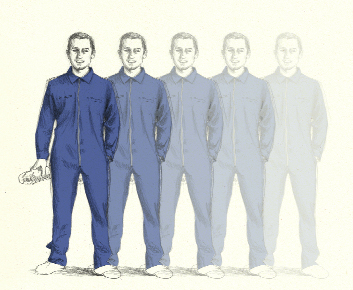

The other recession, though, the one with the loss of “good factory jobs” and systemic unemployment – I fear that this recession is here forever.

Why do we believe that jobs where we are paid really good money to do work that can be systemized, written in a manual and/or exported are going to come back ever? The internet has squeezed inefficiencies out of many systems, and the ability to move work around, coordinate activity and digitize data all combine to eliminate a wide swath of the jobs the industrial age created.

There’s a race to the bottom, one where communities fight to suspend labor and environmental rules in order to become the world’s cheapest supplier. The problem with the race to the bottom is that you might win…

Factories were at the center of the industrial age. Buildings where workers came together to efficiently craft cars, pottery, insurance policies and organ transplants – these are job-centric activities, places where local inefficiencies are trumped by the gains from mass production and interchangeable parts. If local labor costs the industrialist more, he has to pay it, because what choice does he have?

No longer. If it can be systemized, it will be. If the pressured middleman can find a cheaper source, she will. If the unaffiliated consumer can save a nickel by clicking over here or over there, then that’s what’s going to happen.

It was the inefficiency caused by geography that permitted local workers to earn a better wage, and it was the inefficiency of imperfect communication that allowed companies to charge higher prices.

The industrial age, the one that started with the industrial revolution, is fading away. It is no longer the growth engine of the economy and it seems absurd to imagine that great pay for replaceable work is on the horizon. This represents a significant discontinuity, a life-changing disappointment for hard-working people who are hoping for stability but are unlikely to get it. It’s a recession, the recession of a hundred years of the growth of the industrial complex.

I’m not a pessimist, though, because the new revolution, the revolution of connection, creates all sorts of new productivity and new opportunities. Not for repetitive factory work, though, not for the sort of thing ADP measures. Most of the wealth created by this revolution doesn’t look like a job, not a full time one anyway.

Everyone owns a factory

When everyone has a laptop and connection to the world, then everyone owns a factory. Instead of coming together physically, we have the ability to come together virtually, to earn attention, to connect labor and resources, to deliver value. Stressful? Of course it is. No one is trained in how to do this, in how to initiate, to visualize, to solve interesting problems and then deliver. Some see the new work as a hodgepodge of little projects, a pale imitation of a “real” job. Others realize that this is a platform for a kind of art, a far more level playing field in which owning a factory isn’t a birthright for a tiny minority but something that hundreds of millions of people have the chance to do.

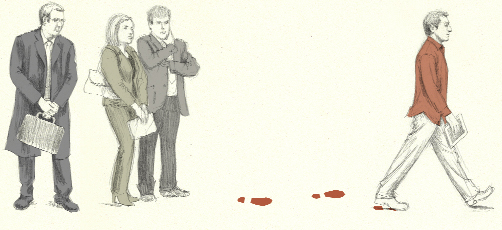

Gears are going to be shifted regardless. In one direction is lowered expectations and plenty of burger flipping. In the other is a race to the top, in which individuals who are awaiting instructions begin to give them instead.

The future feels a lot more like marketing – it’s impromptu, it’s based on innovation and inspiration, and it involves connections between and among people – and a lot less like factory work, in which you do what you did yesterday, but faster and cheaper. This means we may need to change our expectations, change our training and change how we engage with the future. Still, it’s better than fighting for a status quo that is no longer. The good news is clear: every forever recession is followed by a lifetime of growth from the next thing…

Job creation is a false idol. The future is about gigs and assets and art and an ever-shifting series of partnerships and projects. It will change the fabric of our society along the way. No one is demanding that we like the change, but the sooner we see it and set out to become an irreplaceable linchpin, the faster the pain will fade, as we get down to the work that needs to be (and now can be) done.

This revolution is at least as big as the last one, and the last one changed everything.

2. First, connect

In the connection economy, there’s a dividing line between two kinds of projects: those that exist to create connections, and those that don’t.

The internet is a connection machine. Virtually every single popular web project (eBay, Facebook, chat, email, forums, etc.) exists to create connections between humans that were difficult or impossible to do before the web.

When you tell us about your business or non-profit or public works project, tell us first how it’s going to help us connect. The rest will take care of itself.

3. Confidence without guts

Too many MBAs are sent into the world with bravado and enthusiasm and confidence. The problem is that they also lack guts. Guts is the willingness to lose. To be proven wrong, or to fail.

No one taught them guts in school. So much money at stake, so much focus on the numbers and on moving up the ladder, it never occurs to anyone to talk about the value of failure, of smart risk, of taking a leap when there are no guarantees.

It’s easy to be confident when you have everything aligned, when the moment is perfect. It’s also not particularly useful.

4. Fear, scarcity and value

The things we fear are probably feared by others, and when we avoid them, we’re doing what others are doing as well. Which is why there’s a scarcity of whatever work it is we’re avoiding.

And of course, scarcity often creates value.

The shortcut is simple: if you’re afraid of something, of putting yourself out there, of creating a kind of connection or a promise, that’s a clue that you’re on the right track. Go, do that.

5. Before you raise money (assets and expenses)

There are more ways to raise money for your business, project or organization than ever before. There are more angel investors, more online sites, more VCs… it’s true that the local bank has largely abandoned this responsibility, but the web keeps reminding us of the opportunities.

Here’s the key thing you have to understand before you ask your mom or your friends or the local VC for an investment:

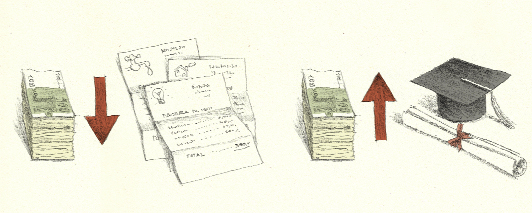

There’s a huge difference between spending money on expenses and spending money to build an asset.

Ice at a picnic is an expense. Once it melts, it’s gone. Your electric bill, rent – these are costs of doing business, and you should rarely if ever borrow money to pay them.

Assets, on the other hand, are things that sustain or grow in value, that you can use again and again, and that are ultimately worth more than they cost.

A college degree from the right institution is an asset. So is an earned list of 10,000 people who want to hear from you by email once a week. So is a reputation (which some people call a brand).

For entrepreneurs, then, the math is simple: any asset-building opportunity that will generate a long-term profit is worth considering and even worth borrowing money to acquire.

But if your business needs to borrow money to simply pay your expenses, to keep you at a steady state, you’re doomed. Unless those expenses are demonstrably building a bigger asset for tomorrow, you’re going to regret the investment, because it’s not an investment, it’s just a waste.

The second thing to keep in mind is this: you probably have to pay the money back. Don’t borrow money to pay for an asset unless you can see a clear path to paying it back. That might mean selling the asset later (which is what VCs almost always do) or it might mean building a project where the asset is so profitable you can pay people back directly (which is why it’s worth borrowing money to go to Harvard Medical School).

If you sell a percentage of your company (which is what most investors ask for) then you’ve basically started down the path to sell the whole thing in order for the investors to get repaid. Nothing wrong with that; just be sure you’re going in with your eyes open.

When in doubt, raise money from your customers by selling them something they truly need – your product.

6. Non-profits have a charter to be innovators

The biggest, best-funded non-profits have an obligation to be leaders in innovation, but sometimes they hesitate.

One reason: “We’re doing important work. Our funders count on us to be reasonable and cautious and proven, because the work we’re doing is too important to risk failure.”

One alternative: “We’re doing important work. Our funders count on us to be daring and bold and brave, because the work we’re doing is too important to play it safe.”

The thing about most cause/welfare non-profits is that they haven’t figured out how to solve the problem they’re working on (yet). Yes, they often offer effective aid, or a palliative. But no, too many don’t have a method for getting at the root cause of the problem and creating permanent change. That’s because it’s hard (incredibly hard) to solve these problems.

The magic of their status is that no one is expecting a check back, or a quarterly dividend. They’re expecting a new, insightful method that will solve the problem once and for all.

Go fail. And then fail again. Non-profit failure is too rare, which means that non-profit innovation is too rare as well. Innovators understand that their job is to fail, repeatedly, until they don’t.