Taking a cinema-driven route through Barcelona means establishing a dialogue between present-day reality and the cinematographic one to help understand the city.

I leave home to take a route that speaks to me of Barcelona seen through cinema. Traversing the city with this aim means establishing a dialogue between the present day reality and a figurative one – in this case, cinematographic – linked by the urban structure, which serves to understand and explain it. So, it is not a set of postcards nor a list of films. On this occasion it must also be short enough, not only in how long the walk is, but also to fit into this article. I see painful sacrifices ahead.

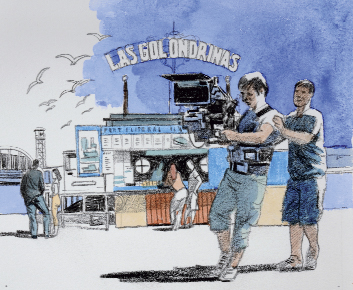

Las Golondrinas

All itineraries need a starting ritual that separates you from the known and internalised reality, that says to you “from here you have to see differently”. I choose to board a Golondrina pleasure boat and leave the city. When it turns round and comes back to port I start my itinerary. The leaving point is always an arrival point.

© El Deseo, DA, SLU

Pedro Almodóvar filming Everything About My Mother, with the Sagrada Família in the background

I am clear about the reason for this beginning: Barcelona, perla del Mediterráneo (1911–1913), which starts on a boat arriving in the port, at exactly the same place the Golondrinas leave from. The crucial entry into Barcelona.

I look at the seafront through 100-year-old eyes, and think about cinematic arrivals into Barcelona. It is from the sea that we observe the grey, moralistic Francoist city of La familia Vila (Iquino, 1950) and, only 10 years later, the Barcelona that is full of light, colour and youthful joie de vivre in Amor bajo cero (Blasco, 1960). On land, in El cerco (Iglesias, 1955) we enter Barcelona through Plaça d’Espanya, in El judas (Iquino, 1952) via Esplugues; in Amor bajo cero others come in through an unrecognisable Diagonal. The arrivals by plane are international: Mister Arkadin (Welles, 1954) and All About My Mother (Almodóvar, 1999), for example.

La Rambla

As Enric Vila would say, to understand the Rambla is to understand Barcelona. And the Rambla has so many cinematographic routes around Barcelona!

We encapsulate the cinematographic history of Barcelona in the Rambla. From the leisure salon in the Teatre Principal, where in 1896 one of the first projections was screened, to the Alexandra, passing through the Rambla, Poliorama, Capitol, Catalunya, and Kursaal cinemas. Another itinerary: that of postcard Barcelona, that of films – far more numerous – that give the city a superficial glance and a somewhat meaningless narrative, that use the Rambla as an easy subject. All About My Mother is the most obvious recent case, although you would be expecting to see Vicky Cristina Barcelona (Allen, 2008) (in fact, we should talk about it quite a lot). We could also go down the Rambla reviewing movies where the history of Barcelona is the plot and, at some points, the city is the backdrop. La ciutat cremada (Ribas, 1976) pops into my head, with a shootout on the rooftop of the Betlem church, among others.

Carrer de Ferran

Carrer de Ferran reminds me of Perfume (Tykwer, 2006). The main character strolls down this street and behind him you see Plaça de Sant Jaume. I think about another route: of cinematographic anachronisms. Although we believe that we are in 18th-century Paris, at that time there was no street and the square was not as built up as it is today.

There must be someone dedicated to collecting these errors in a blog. It would not surprise me.

© Mediapro – Antena 3 Films / Gravier Productions / Álbum

Scarlett Johansson strolling down the Rambla in Vicky Cristina Barcelona, by Woody Allen (2008)

Plaça d’Antoni Maura

Cinema is a typical example of the plausible transformation of reality. The same person can be Moses and an astronaut and make us believe both. Barcelona is cinematographically flexible enough to portray fictional times and locations different from its own.

I reach Plaça d’Antoni Maura. It is unashamedly dominated by two powerful buildings, the home of the Foment del Treball and the Caixa Catalunya building (up until 1953, the Banco de España headquarters). The square is named after a liberal conservative and is crossed by Via Laietana. There are few more capitalistic places in the city.

In 1957, in Rapsodia de sangre, by Antonio Isasi-Isasmendi, this square felt the repression exerted by Communist power. In this movie the Barcelona of the Franco era becomes Stalinist Hungary, convulsed by the population’s desire for change: a peaceful demonstration is completely quashed by the most vicious communist police in front of these two facades.

Walking down Via Laietana I go through other films in which Barcelona is a character actor, like The Great White Hope (Ritt, 1970), where the Parc de la Ciutadella is a Berlin park and the Olympic Stadium on Montjuïc is the hippodrome in Havana; or Voyage of the Damned (Rosenberg, 1974), where the port is Hamburg. Montjuïc castle belongs to Henry IV in Falstaff – Chimes at Midnight (Welles, 1965). I smile as I think about others cases where Barcelona plays a really awful role: Park Güell is Fu Manchu’s castle in The Castle of Fu Manchu (Franco, 1969), the Saló del Tinell and the Santa Àgata chapel are Dracula’s castle in Dracula (Franco, 1970), and the Collserola uplands are the African jungle in Tarzan and the Jungle Mystery (Iglesias, 1973).

Plaça del Rei

In every itinerary the end point is as important as the start. It must summarise, conclude and, if possible, surprise. It should leave behind it a good memory of the trip, reinforce the links with the view taken and the taste for what has been learnt. And if it can, the feeling that being footsore was worth it.

I finish my route with a pit stop at one of the tables in Plaça del Rei. A few metres away is the filming location of yet another of those 1950s movies that portray the city so well: El ojo de cristal (A. Santillán, 1956). In this sequence, some kids tell stories about a glass eye without realising, yet, that they are on the trail of a killer. The technique of plot–counterplot shows us the Plaça del Rei with the Tinell staircase behind the first child, and the facade of Casa Padellàs as the backdrop to the second. If we look behind the first kid there are three people using a pulley to raise a huge stone or box to the terrace of the Santa Àgata chapel. Behind the second are another three people going into a public building.

© Isasi Producciones / Álbum

A scene from Rapsodia de Sangre [“Blood Rhapsody”], a 1957 film setting Communist Hungary in Franco-era Barcelona

They enter the Museu d’Història de la Ciutat, which had opened a few years beforehand. I like to think that the stone they are awkwardly lifting with a rope has been recovered from an excavation by Duran i Sanpere, the promoter and director of the museum.

A third element fascinates me: the second child is sitting on the base and leaning against the column of a stone pillar. It is one of the great columns of the August de Barcino temple. The pillar was in the Plaça del Rei, accessible to everyone, until precisely the year the film came out, when it was moved to its current location in the temple site on Carrer del Paradís, to be admired, and historically revered, at a museum-like distance.

On the one hand, then, the contemporaneity of the film blends with the city’s past (all of Barcelona’s historical periods can be found in Plaça del Rei); on the other, the kids tell stories about the present facts (and guess right!), while not far away the city finally starts reconstructing the things that it has lived through. Something it still has not finished doing. So, just in this brief moment of Barcelona cinema, the city is revealed in all its narrative historicity and historical narrative, in a game of smoke and mirrors where the boundaries between reality and fiction dissolve in a glance through an urban itinerary.