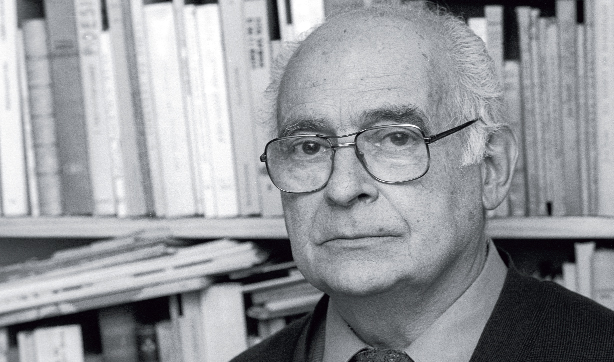

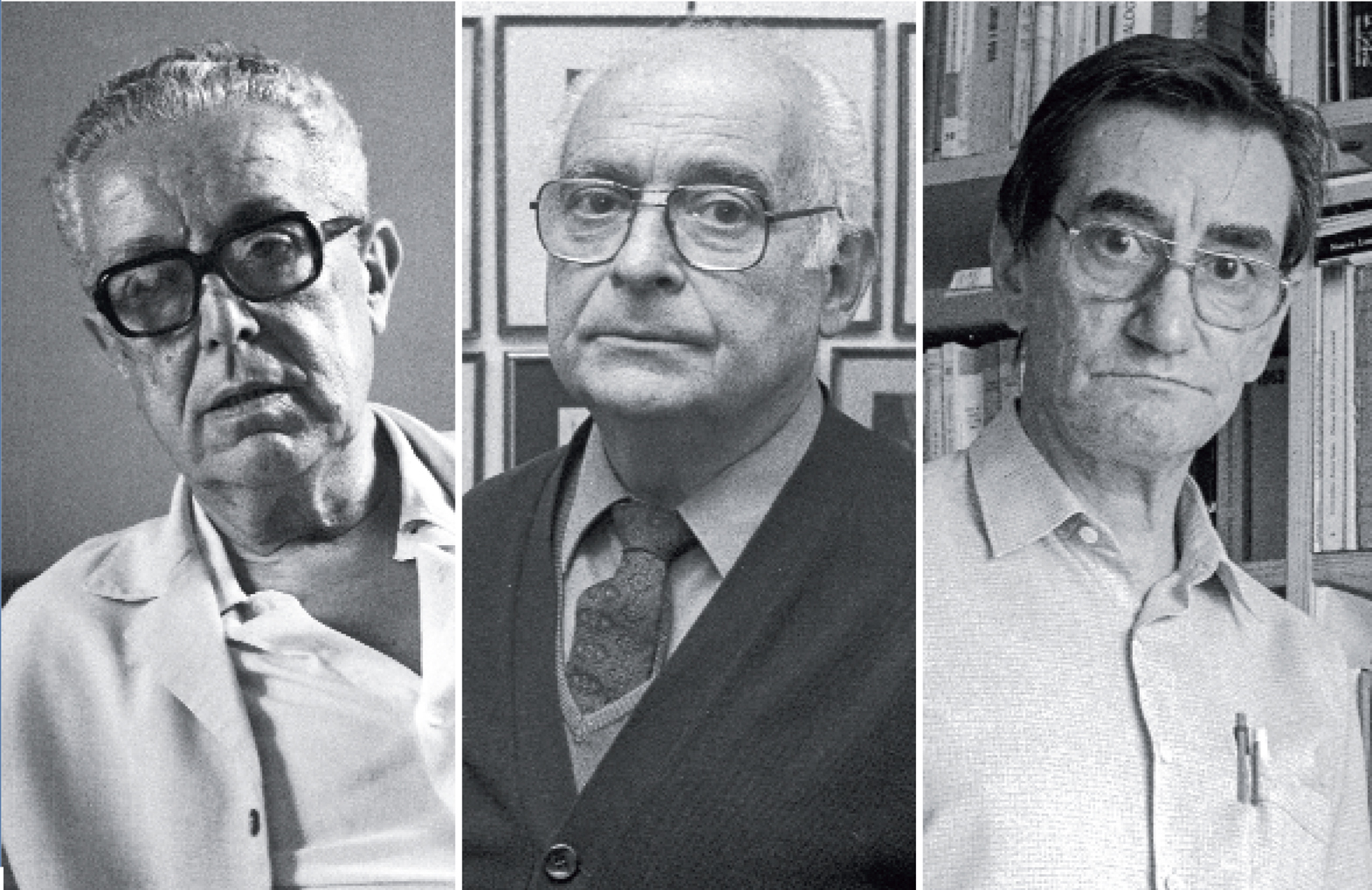

Photo: Robert Ramos

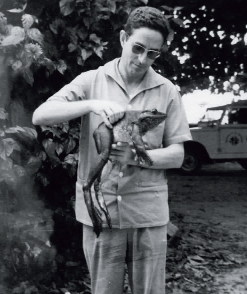

From left to right, activist and writer Maurici Serrahima in 1977, editor and poet Josep Pedreira in 1986, and Miquel Porter Moix, cultural promoter and cinema historian in 1985.

For subsequent generations, the 1950s have always been a rather undefined, vague period, faded away in the long history of Franco’s dictatorship. The first post-war decade of the 1940s was terrible, but the years after dragged on even more, with any hopes of a swift change of the political landscape dashed and the death of the dictator still seeming a long way off.

Even so, during that difficult decade of the 1950s, initiatives that would pave the way to the cultural boom of the 1960s came onto the horizon and began to take hold. And what is quite remarkable is that the most ambitious and fruitful of these initiatives were imbued with a strong sense of modernity. Rather than going against one another, anti-Franco cultural resistance and a sense of cultural modernity went hand-in-hand through those times.

This feature article is dedicated to the roles and the works of three intellectuals and cultural activists who became paradigms of resistance and modernity: essayist Maurici Serrahima, publisher of poetry Josep Pedreira, and film lecturer and cultural promotor Miquel Porter.

The underground modernity of the 1950s –Serrahima, Pedreira and Porter

Photo: Robert Ramos

An image of the dark years of the 1950s: the blessing of automobiles on Saint Christopher’s day at the chapel on Carrer Regomir in July 1958, with a Biscúter in the foreground.

Under the prohibitions of the dictatorship, new cultural codes were forged that finally came to full fruition after the death of Franco and the return to democracy. The pioneers of the 1950s laid the foundations for this cultural boom.

The 1950s are the least well-known years of our recent cultural history. The 1940s are considered the decade of total repression, of radical and absolute prohibition of our language and of all displays of Catalan culture. Josep Benet offers a fine explanation of this in his book Catalunya sota el règim franquista [Catalonia under Franco’s Regime], published in Paris by the unofficial Catalan Institute of Political and Social Studies in 1973 (remember, Franco didn’t die until November 1975). “Once the city of Barcelona had been occupied – writes Benet – one of the first measures taken by the government of General Franco was to abolish the official status of the Catalan language in Catalonia. But it also took even more radical measures, namely the absolute prohibition of the public use of the Catalan language anywhere in Catalonia. With the announcement of the first edict published by the highest authority of Franco’s occupation, the victors of the Spanish Civil War officially established that, as of the moment of occupation, the use of the Catalan language would only be permitted within the confines of family and private life.” Benet goes on to add, “On few occasions […] in modern times has such a radical and absolute official ban been placed on the use of a people’s living language”.

This situation continued until 1945, when the allies won the upper hand in the Second World War and Hitler and Mussolini were defeated. In his work La cultura catalana: entre la clandestinitat i la represa pública (1939-1951) [Catalan Culture: Between Secrecy and Public Repression (1939-1951)], Joan Samsó talks of the existence in 1946 of “an opening” through which the magazine Ariel, to name one example, was able to channel itself. However, this opening soon proved to be ephemeral and Ariel was quickly banned, while those responsible for publishing it were arrested and sent to trial.

And later came the 1960s, which were the years of great economic and social change. The 1950s, however, faded in the long history of Franco’s dictatorship. Maria Aurèlia Capmany recommended to the young aspiring writers who went to visit her in the 1970s that they count the post-war years one by one – 1940, 1941, 1942… – in order to grasp how interminable they were. Of all of these years, the 1950s must have been the most interminable, because any hopes of a swift change had been dashed and the death of the dictator still seemed a long way off. Nevertheless, during this decade initiatives that would pave the way for the cultural boom of the 1960s came onto the horizon and began to take hold. And what is quite remarkable is that the most ambitious and fruitful of these initiatives were imbued with a strong sense of modernity. Rather than going against one another, anti-Franco cultural resistance and a sense of cultural modernity went hand-in-hand through those tough years of the 1950s. I present three examples: the essayist Maurici Serrahima, publisher of poetry Josep Pedreira and the film lecturer and cultural promotor Miquel Porter.

Maurici Serrahima, writer and activist

Maurici Serrahima (1902-1979) wrote a diary, finally published in six volumes, that spans the years from 1940 to 1974. It consists of thousands of pages of essential and underrated reading that paints a picture of Barcelona’s cultural life and its evolution over this period. Serrahima was an excellent writer. This can be seen in his essays and his novels, as pointed out by Pere Gimferrer in the prologue to the last volume of those diaries: “Serrahima became one of the great contemporary Catalan writers, one of the few undeniable exemplars of a prose that is at once artistic and colloquial, stylised and unaffected.”

In 1929, Serrahima was one of the signatories of the founding manifesto of the Democratic Union, the Catalan counterpart of the Italian People’s Party – the forerunner of the Christian Democracy party, founded in Italy by Don Luigi Sturzo. His participation from a very early age in Catalonia’s political and intellectual life did not stop him from paying close attention, also from an early age, to what was happening in the most advanced spheres of Europe. In 1929, he undertook what he referred to as an “in-depth study of Chesterton”, the English writer who converted to Catholicism in 1922. Chesterton’s name appears repeatedly in his diary, for example, in reference to the biography of Chesterton by Maisie Ward, published in Argentina, which he read in 1949. He was greatly impressed by the quality of the translation, which he later found out to be the work of Cèsar August Jordana, a Catalan engineer and writer exiled in Argentina who earned his living in this way.

When talking of Chesterton, Serrahima associates him with Josep Pla – “he mixed lucid insight with errors of information” – and with Dickens, one of the writers of whom Chesterton had written from a certain distance. Serrahima considers Chesterton to be one of his two great influences, the other being Josep Maria Capdevila. The fruit of Serrahima’s interest in the former’s work is the volume Chesterton, published in Spanish in 1941 by Josep Janés.

Another of the great writers who inspired the intellectual and civic activity of Maurici Serrahima was Emmanuel Mounier (1905-1950), the French Catholic thinker and “inventor” of the so-called “personalism”. This current of left-wing Catholicism became very influential in France, but also in Catalonia. The politicians Jordi Pujol and Pasqual Maragall, seemingly so dissimilar, have both declared themselves to be adherents. Serrahima was the person responsible for bringing Mounier’s philosophy to Catalonia, and his role was so important that in 1936 he was named the Barcelona correspondent of the magazine Esprit, of which Mounier was the founder and director. When, during the Civil War, Serrahima was detained by the Republican government’s secret service, Mounier intervened to secure his release. Once in exile in Bordeaux, he wrote a report for Mounier on the Civil War that still constitutes one of the most lucid analyses of the conflict. Serrahima did not want it to be published until 1984, when he assumed that democracy would have been returned to Catalonia and Spain, and therefore his critique of the Republican government, and above all of President Companys, could not be used as a means of discrediting the country.

Marcel Proust was another of the writers and thinkers on whom Maurici Serrahima became an acknowledged specialist. In 1951, in the same collection in which the text dedicated to Chesterton appeared, an essay by Serrahima was to be published dedicated to Proust. However, censorship put a stop to the publication. Serrahima included the notes he had prepared in his prologue for the complete Spanish edition of Recherche, published by Janés. Finally, in 1971, his essay on Proust was published in the collection Antologia Catalana [Catalan Anthology] by Edicions 62, a publishing house run by the university lecturer Joaquim Molas. In the prologue to the volume, Molas states that Serrahima shows a knowledge of “all the nooks and crannies of Proust’s work”, as well as of the main studies that authors such as André Maurois and Henri Massis had published on that work.

Serrahima carried out all this activity in a way that might best be described as complementary to his profession as lawyer and the task he had set himself as a cultural activist. For example, in 1947 he created the Miramar Group, which brought together some of the most dynamic young Catalan nationalists. They organised poetry readings, literary competitions and debates on historical topics. One of these debates, which he described in his diary, tackled the differences between Athens and Sparta. This topic may seem far removed from the everyday problems of that time, but the aim was for the young debaters to learn the value of democratic confrontation should liberty one day be restored to Catalonia and Spain.

Serrahima was a friend and, to a certain degree, confidant of both Josep Maria de Sagarra and Josep Pla, and furthermore was a co-conspirator of Josep Benet. He maintained good relations with the incipient democratic groups that began to take shape in the rest of Spain, and he acted as advisor to some of the country’s most important patrons. All of this activity naturally took up much of his time, and to a certain degree, it outshone his literary work. He was appointed Royal Senator in the elections of 1977, the first to be held after Franco’s dictatorship.

Josep Pedreira and Els Llibres de l’Óssa Menor

Josep Pedreira (1917-2003) is another paradigmatic case of this combination of cultural resistance and literary modernity; or, better put, of how cultural resistance was carried out largely in the name of a prohibited literary modernity, which it aimed to recover. Pedreira was neither an intellectual nor a patron with any sort of fortune, but a graphic artist who dedicated his talent and his work to publishing poetry in Catalan. A native of Barcelona, he had spent a large part of his childhood in Galicia, where his family originated from. On returning to Barcelona as a teenager, he began working at the same time as he began his studies at the Llotja Advanced School of Art and Design (ESDA), where he came into contact with students from the National Federation of Students of Catalonia (FNEC) and became a proponent of a peaceful but radical Catalan nationalism. During the Civil War, he ended up in the Red and Black column of the anarchist groups. Then, in the post-war period, he began to work with the publisher Josep Janés.

In 1949, of his own initiative, Josep Pedreira began to put together what would be one of the most important collections of post-war Catalan poetry: Els Llibres de l’Óssa Menor (The Books of Ursa Minor). The opening edition saw the first-ever publication of one of Salvador Espriu’s seminal works, Les cançons d’Ariadna (The Songs of Ariadne). From 1949 to 1963, 52 volumes of poetry were published within the Els Llibres de l’Óssa Menor collection. This figure indicates that Pedreira must have made a significant effort in terms of financing, if we bear in mind that he was not a rich man and that the subscription system he set up when he began the project was not sufficient to cover all the costs. Pedreira had to dedicate a large part of his modest salary as an employee at the publishing house owned by Janés and at other companies in the publishing industry, in order to cover the losses incurred by the collection. He only had the financial support of his wife, who earned a good living writing books for housewives. Pedreira ended up ruined, debt-ridden and in poor health.

In 1963, the collection was purchased by the industrialist Joan B. Cendrós, one of the founders of Òmnium Cultural and the owner, at the time, of Editorial Aymà publishing house. Pedreira continued to maintain ties with the collection and with its yearly poetry prize, but he was deeply affected by the experience. In letter sent to Joan Fuster in April 1965, he wrote: “A further clarification, or perhaps two: not only have I surrendered unconditionally (for the time being, later on you will receive better news), but also, and I say this with no reproach, poetry has led me to a veritable catastrophe, firstly material and secondly moral.”

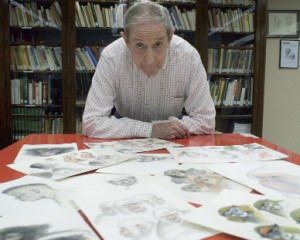

Photo: Fons Josep Pedreira. UAB

Salvador Espriu, Joan Teixidor, Josep Pedreira, Jaume Bofill i Ferro, Marià Manent, Josep Janés, Josep M. de Segarra and Tomàs Garcès.

It was amidst hundreds of setbacks involving censors, authors, distributors and booksellers that Pedreira finally managed to publish Els Llibres de l’Óssa Menor. Franco’s authorities had initially followed a policy of strict prohibition. Later, they seemed willing to tolerate books published in Catalan as long as they followed language models from before the time Pompeu Fabra established the linguistic rules of modern Catalan. Finally, and above all following the Nazi and fascist defeat of 1945, bold publishers like Pedreira forced Franco’s regime to face up to reality. This made it possible for the first ten books published by Pedreira to feature three of the most radical post-war writers and poets: Salvador Espriu (1913-1985), Joan Vinyoli (1914-1984) and Joan Perucho (1920-2003).

The first edition of Les cançons d’Ariadna consists of thirty-three poems – this number would grow to one hundred in the definitive version – and a prologue by Joan Perucho. As Gabriella Gavagnin pointed out in his study, the book’s narrative material is based on a series of myths: from the classics, with Ariadne abandoned on Naxos; from Egypt, with Isis’s search for the dismembered body of Osiris; from oriental stories and legends, with the rage of the King Ctesiphon and the sadness of the princess of the Yangtze River; and biblical myths, with the tragic story of Rizpah and the Jewish exodus. But it also contains references to Poe and to Wagner’s The Flying Dutchman, and alludes to contemporary events, such as an American soldier who goes to war, or the dangers of the atomic bomb.

In 1951, with his work Les hores retrobades [The Recovered Hours], Joan Vinyoli won the second Óssa Menor prize organised by Pedreira. This poet had previously published Primer desenllaç [First Denouement; 1937] and De vida i somni [On Life and Dreams; 1948]. In Vinyoli’s poems, the critics pointed out the influences of Goethe, Rilke, Hölderlin and Hofmannsthal. In this new book, Vinyoli left behind his descriptions of landscapes and began to form his own voice, markedly elegiac, that did not cast off the aforementioned influences but rather wove them into his work in an ever-more natural manner. And he added new voices, which his biographer, Pep Solà, identified as belonging to Luis Cernuda, Santa Teresa de Jesús and Shakespeare in The Tempest.

The runner-up to the prize won by Vinyoli was Joan Perucho with Aurora per vosaltres [Aurora for You], a book which Pedreira managed to publish that same year in 1951. It may not be one of this writer’s most significant books, but what is interesting is the radically modern perspective shown by Pedreira in publishing Perucho at that time. A few years later, in the same collection, El mèdium [The Medium] was published, which calls up the world of spirits and apparitions, in which Perucho was so interested, and which is closely linked to a certain republican and anarchist tradition of Catalan nationalism. Moreover, it is worth remembering the relationship between the Perucho’s work and that of Lovecraft and other authors who are not listed in the Western literary cannon.

Miquel Porter: from silent to Soviet film

Miquel Porter Moix (1920-2004) was an intellectual, a writer and a cultural agitator who dedicated most of his energy to the world of film. The son of Josep Porter, who became one of Barcelona’s most important booksellers, the first films he recalls – in the book-interview published by J. M. Garcia Ferrer and Martí Rom – were the Soviet films screened in the cinemas of Barcelona during the Civil War: Baltic Deputy, Chapaev, Son of Mongolia, etc. The impact of these films on Miquel Porter, then in his teens, nourished an interest in Soviet film, in which he became a true specialist over the years. In 1939, however, not only did Soviet films disappear from the golden screens of Barcelona, but likewise any film whatsoever that did not fall within the framework of the prevailing national Catholicism.

A student of Philosophy and Arts at Barcelona University, as soon as he was awarded his degree in 1955 he knew that he wanted to dedicate his career to the world of film. As Barcelona was a cultural vacuum, Miquel Porter began by starting a family film club, with tickets and programmes and what not. He set it up on the first floor of a palace on Portal de l’Àngel which was also used as storage space for the bookshop owned by his father, directly below. With its entrance on Carrer de la Canuda, this was a room where Porter managed to screen films of all kinds.

Later on, he became friendly with Henri Langlois, Director of the Filmothèque in Paris, and with Raymond Borde, of the Toulouse cinema. Through these two institutions and the French Institute in Barcelona – where he organised the Lumière Circle – Porter managed to obtain more films for his sessions. But he was not satisfied, and in the mid-1950s he created the Catalan Cinematic Collection; (COCICA), a kind of private cinema that he organised and managed in the apartment on Portal de l’Àngel. He rented and bought films in the Encants flea market in Plaça de les Glòries, sometimes by weight. And, without any kind of permission, he organised film and debate sessions during which he screened some of the most important films in the history of cinema, from the most classic to the most modern: Metropolis, Battleship Potemkin, The 400 Blows, The Seventh Seal, Wild Strawberries and The Hunt.

Photo: Fons Miquel Porter i Moix. UB

Miquel Porter in the museum space of the Catalan Cinematic Collection, which he created in 1964 on the first floor of the Palace of the Marquis of Barberà and la Manresana, above his father’s bookshop on Portal de l’Àngel.

Later, in the mid-1960s, when film and debate sessions became all the rage, Porter was one of their foremost proponents. Bear in mind that most of these activities were organised without any type of permission, although they were sometimes supported by different religious or cultural organisations, and that Porter frequently ran into legal problems. This resulted in the Civil Guard turning up and banning such initiatives.

Porter travelled all over Catalonia at a time when there were no motorways. He recounts that on one occasion he had to do part of a journey in a lorry that collected milk from farms. The film and debate sessions were not merely a cultural activity. They were also a breath of fresh air that could call into question practices and customs in the fields of morality, religion or sexuality. He even found time to maintain contact with the promotors of the artistic avant-garde that came out of central Catalonia, such as Club 49; to be one of the promotors of the magazine Curial, and, later, to be one of the founders of Els Setze Jutges [The Sixteen Judges], the group which, beginning in the early 1960s, aimed to create songs in Catalan that would appeal to a wide public. Also in the early 1960s, Porter began to work as a film critic for the influential magazine Destino, and later, as of 1976, for Avui, the first official Catalan-language newspaper to appear after the death of Franco.

In 1969 he was invited to become the first Professor of the History of Film. When Catalonia regained its political autonomy, Miquel Porter – by then already a member of the Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC) – was appointed as the first Head of the Film Department of the Ministry of Culture. While he held this post, he tried to lay the foundations for the country’s own policies regarding film. In 1986, he gave up politics but not cultural activism. That same year, he published Renoi, quina portera! [Wow, What a Concierge!], his only novel. From 1990 to 2004, he held prominent positions in the Catalan Federation of Trade Unions (CSC), and in 1996, he was appointed Rector of the Catalan Summer University (UCE).

Militancy and creativity

Photo: Colita / Corbis

The singer Raimon, born just after the Civil War, who became the voice of the rage of the generation of the ‘70s in

When historians analyse the long Franco’s dictatorship, they tend to remark on the great economic and social change that took place in the 1960s. And this is quite right. During the course of this decade, Spain stepped into the modern age. This occurred, as explained by Paul Preston in his essential biography of Franco, not with the support of the dictator, but rather with his utmost incomprehension. Franco never understood the workings of the modern economy and it was the Inland Revenue Minister Navarro Rubio who, using examples suitable for a class of primary school children, had to explain to him that if Spain did not apply the measures put forward by the World Bank, in a few short weeks it would have to declare itself bankrupt.

Modernisation did not only affect the economy. At the end of the 1960s, the first generation of Spaniards and Catalans born after the Civil War came of age. And then there was tourism, which was making a decisive contribution to the modernisation of customs, a modernisation that was also stimulated by society’s unstoppable move away from religion. As the university lecturer Joan B. Culla explains in the seventh volume of Història de Catalunya [History of Catalonia; supervised by Pierre Vilar and published by Edicions 62]: “The dwindling congregations in church, the sharp fall in the number of new priests and the loss of social influence of the Catholic Church are merely the symptoms of a more general crisis of authority and traditional values, which is felt above all in the bosom of the family.”

The 1960s saw the consolidation of the two ideologies that would make up Catalonia’s political and social majority as it came out of the dictatorship: a Catalan nationalism with more or less Catholic roots, and a left-wing social current with Marxist roots. The antidemocratic laws that governed the country from 1939 onwards did not change until after the death of the dictator. Spain therefore continued to be deprived of its liberties and Catalonia of its right to its own language and culture.

However, under the prohibitions of the dictatorship, new cultural codes were forged that finally came to full fruition after the death of Franco and the return to democracy. In 1960, Espriu published La pell de brau [The Bull’s Skin]; in 1962, Mercè Rodoreda published The Time of the Doves; 1963 saw Raimon rise up as the spokesperson for the rage of the generation of the 1970s, as well as the publication of the anthology Poesia catalana del segle xx [20th century Catalan Poetry] by Josep M. Castellet and Joaquim Molas, one of the most controversial attempts to keep up with modern European literary trends; 1966 was the year of the so-called Caputxinada, which gave rise to the first unitary political action groups – clandestine of course – which culminated in the creation of the Catalan Assembly. Many of the values and benchmarks of current-day Catalonia had their beginnings in the 1960s. We cannot understand this period, however, without considering the cultural initiatives from the decade that preceded it, by necessity hidden even further underground.