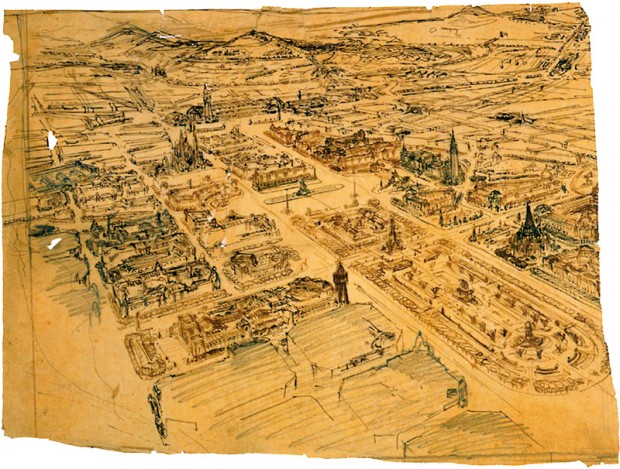

Léon Jaussely’s proposed ‘connections plan’ took advantage of Cerdà’s design for Plaça de les Glòries to connect with the surrounding towns. Jaussely was the first foreigner to win a town-planning competition in Barcelona. His proposal included an enormous rectangular civic concourse bounded by Avinguda Meridiana, Carrer de València, Carrer de Marina and Carrer de Sardenya.

Photo: Barcelona City Council. Town planning

What would the other Barcelona have been like? The one that was imagined but frustrated for financial or political reasons or because of changing fashions, the one that was put away in a drawer to wait for better times or the one of projects short-listed in competitions they didn’t win in the end. We visit it on the following lines.

The Barcelona that never made it is the subject under study in La Barcelona desestimada. L’urbanisme de 1821 a 2014 (Àmbit, 2017), by Carme Grandas, a Doctor in History of Art. The book provides a broad and varied review of hundreds of architecture competitions and unique projects from the first third of the 19th century (disentailed land around the Rambla) until today (Plaça de les Glòries Catalanes or the plan for 16 urban accesses to Collserola Park, known as the Portes de Collserola – Gates to Collserola). In this article we’ll look at some of the projects that were turned down for a variety of reasons and what this alternative Barcelona would have looked like.

We’ll start in modern Barcelona’s biggest park, as designed by Josep Fontserè. His aim was to build a space devoted to industry and science where once there had been a fortress. Shaped like a horseshoe, it was to have a marked symmetrical nature, like French gardens. In the middle there would be an enormous circular palace devoted to industry, where exhibitions and fairs would be held, and an enormous open space between the palace and the fountain with a little waterfall. The fountain was one of the few elements from the original project to be saved, along with the water tank, the shade house and the building of the Museum of Geology. There was a proposal to make the waterfall much bigger but it would have endangered the financing of the palace. Fontserè took demolition to the extreme; not a single building of the old barracks was left standing.

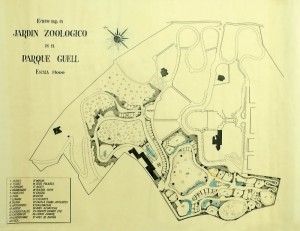

Plans by Nicolau M. Rubió i Tudurí to move the zoo to the west side of Park Güell, dating from the 1960s.

Photo: Contemporary Muncipal Archive of Barcelona

Moving the zoo to the Park Güell could have been a resounding success when the architect Nicolau M. Rubió i Tudurí suggested it in the 1960s, at a time when the animals were in a sorry state of neglect. As he envisaged it, the zoo would occupy the western side of the park, between Avinguda del Coll del Portell and Avinguda del Santuari de Sant Josep de la Muntanya. The animals would gain in space and salubrity and Gaudí’s Washerwoman, with her arm raised right in front of the tigers’ cage, would be a wonderful sight for visitors.

Dreta de l’Eixample and Guinardó, downtown

We take Avinguda Meridiana towards the city centre foreseen in the Cerdà plan, Plaça de les Glòries Catalanes. This is one of Cerdà’s great successes, which León Jaussely, the first foreigner to win a town-planning competition, was able to take advantage of with his 1905 ‘connections plan’. The object of the competition was to plan the connection between the Eixample and the towns on the plain. Jaussely also planned something that never materialised, an enormous civic concourse between Avinguda Meridiana, Carrer València, Carrer Marina and Carrer Sardenya. It would have looked like Washington or Paris, with large-scale baroque-style buildings, among them the City Hall.

Another virtue of Jaussely’s plan was the public transport network, which would have made it possible to get everywhere by tram and have rapid access to the Central Station, located on Carrer Indústria and envisaged as a nerve centre full of life. This was within walking distance of a nymphaeum built at the foot of the Rovira hill, from which people could enjoy a wonderful view over Carrer Dos de Maig. Jaussely wanted to fill Barcelona with avenues with spectacular endings. The monument on the macro-roundabout at the meeting of Avinguda Diagonal, Avinguda Meridiana and Gran Via would have had nothing to envy the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. But in the 1960s a spaghetti junction was built there with four branches… And we all know what happened after that.

Jacint Verdaguer and Àngel Guimerà, suitably honoured

It’s worth stopping at the monument to the poet Jacint Verdaguer, farther up Avinguda Diagonal. Choosing the winning project was difficult, as almost 40 proposals were submitted to the public competition. In many of them the poet appeared seated, presiding a group of allegorical figures relating to his work, with the Catalan homeland and his religious visions as recurrent themes. The sculpture eventually chosen and inaugurated in 1924, the one we all know, shows Verdaguer standing, and even then, at the end of the Modernista period, the style was already old-fashioned.

The writer Àngel Guimerà, who enthusiastically attended the inauguration of this monument, would have had his own, slightly more modern monument in Plaça de John F. Kennedy. The architects Rubió i Tudurí and Puig i Cadafalch used architectural references more characteristic of the 30s: a terrace in the form of a ship’s prow – inspired by Mies van der Rohe’s project for a monument to Otto von Bismarck in Bingen –, an enormous obelisk as the fashion of the time dictated (Piazza del Popolo in Rome, the monument to the Republic in Paris…) and sculptures relating to Guimerà’s plays. The site was to be suitably crowned with an imperial eagle and a Catalan flag. Going up Carrer de Balmes, on catching sight of the monument, one would have imagined they were bound irremediably to crash into Captain Saïd’s ship in Guimerà’s play Mar i cel (Sea and Sky).

Plaça de Catalunya by Pere Falqués (1891), with arches, pavilions and radiating crossings.

Photo: Institut Muncipal d’Hisenda

A central Plaça Catalunya

The centre of the city is one of the places that has given rise to most architectural and aesthetic debate. Before going on, let’s take an imaginary rest under the arches designed by Pere Falqués for the Plaça Catalunya of 1891 and never built. This city square had a hard time taking shape as such. Cerdà hadn’t planned it and for a long time it was just a hole in the urban fabric, the site of vegetable gardens, sheds and workshops. Falqués thought that carriages could cross it by radiating lanes, trams could go round it and pedestrians could cross it under covered archways and pavilions. Lluís Mumbrú proposed building an artificial waterfall there on the occasion of the Universal Exposition of 1888. It was to be nine metres wide and there would be fascinating fish ponds at the top. The view of the water and rocks would give the feeling of being at the Lake Valley Park, the short-lived leisure facility at the Vallvidrera reservoir.

Plaça de Catalunya would have been easy to locate thanks to the skyscraper that was to preside it. The Sellés Miró Tower, named after the promoter, would introduce 20s North American architecture. It was to stand 100 metres above street level, with 27 floors given over to a hotel and offices, and would have occupied the whole of the Bergara-Pelai block.

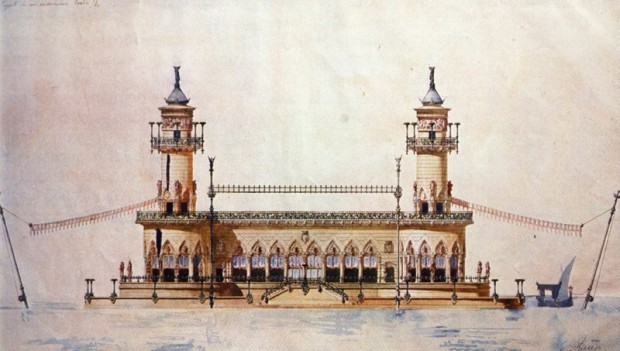

Study for an embarkation building in the city port, drawn up by Gaudí when he was still a student at the Barcelona School of Architecture.

Photo: Roial Gaudí Chair

The city centre could also have been a good place for Gaudí’s work. Going down the Rambla, we would have come across one of the 20 newsstands he designed in 1880 for Enric Girossi, but which were never built because of a lack of funding. They were to be built from iron and glass and would play an interesting twofold role: flower stalls on one side and urinals on the other. Gaudí’s most outstanding imprint, though, would have been the monument to the Catalan King James I, in Plaça del Rei, for which the first stone was laid on 27 June 1908. Gaudí designed three Gothic arches leading from Plaça del Rei to Via Laietana under the chapel of Santa Àgata.

The seafront, Barcelona’s best side

We’re lucky that Barcelona turned towards the sea at the same time the walls were demolished, with proposals that embellished the seafront. As well as the street lamps in Plaça Reial (these we can admire), Gaudí designed more for the promenade now known as Passeig de Colom – lamps that had been electrified by 1878 and that were more than 20 metres high –, as well as a beautiful embarkation building for the Port Vell.

Right next to the entrance to Parc de la Ciutadella from the sea end, and connected to the other scientific institutions that were already there via a bridge over the street, was to be the Institut Oceanogràfic de Catalunya (Oceanographic Institute of Catalonia), a project by Antoni Falguera presented in 1919. It was a very large building, intended as an international point of reference for the marine sciences and for teaching about the Mediterranean. Its own little embarkation building with a flight of steps flanked by pavilions, the enclosed port and the lighthouse made it a first-rate public space.

And between here and the Besòs we could have enjoyed a series of ‘superblocks’ along the seafront, designed by Bonet i Castellana in 1965 as part of what was known as the Pla de la Ribera (Shoreline Plan). These were city blocks measuring 500 x 500 metres, reclaimed from the sea and standing six metres above it. They would be free of cars because this architect’s idea, as he himself wrote, was to get rid of the incoherent combination of ‘man, walking at three kilometres an hour, and the spate of vehicles trying to reach 80 kilometres an hour’. A model seafront and an example of life quality.

Bonet i Castellana also took part in the design of Les Pedreres, on the side of Montjuïc overlooking the sea. This was a series of blocks and streets — also conceived by Oriol Bohigas and Josep M. Martorell — perched on the steep slope and forming a neighbourhood of 4,000 homes. More privileged residents, like the ones on the superblocks. Ten minutes from the city centre, but without the noise and with the sea lapping at the front door, so to speak…

Being so far away and so big, it would take us too long to visit the slaughterhouse that was to be built to satisfy the growing needs of Barcelona in the late 19th century. Located at Camp de la Bota, on a site measuring 2.9 hectares (7.1 acres, equal to 26 Eixample city blocks), the project was by Josep Domènech i Estapà, whose Modernisme was less convoluted than that of his cousin, Lluís Domènech i Muntaner. We’d better leave it out then, and head for the area where, not much later and with fewer pretensions, Barcelona’s new slaughterhouse was eventually built, next to the future Plaça d’Espanya.

The urban revolution of Plaça d’Espanya

The 1929 International Exposition was a shake-up for this area. The Plaça d’Espanya designed by Ferran Romeu in 1922 had three virtues that made it very special. One was its size – with large spaces for pedestrians –, a monumental central fountain and the harmony of its six eight-storey façades. The skyscrapers Rubió i Tudurí designed for Avinguda Maria Cristina would lead the eye to the Palau Nacional, an eclectic building of iron with strange Neo-Arabic lines, designed by Benet Guitart. But people would undoubtedly prefer Lluís Girona’s Palau de la Llum, a large iron and glass pavilion which would have looked beautiful lit up at night. Three projects, once again turned down.

During the exposition, a mock-up of part of what was to be the Barcelona conurbation was exhibited. It was also designed by Rubió i Tudurí, who called it ‘La ciutat futura’ (The Future City), and consisted in a series of enormous skyscrapers that lined the Llobregat as far as Martorell and beyond. Numerous roads also went under the skyscrapers to ensure mobility.

The city of rest

Tired of walking up and down? I’m not surprised. Luckily, Barcelona has imagined wonderful ideas for pleasure and leisure, like the Lake Valley Park in Vallvidrera, mentioned above.

In Pedralbes, in 1915, Francesc Cambó commissioned an immense, 300-hectare (740-acre) park from the father of landscape architecture, Jean Claude Nicolas Forestier. The style was French, of course, like a smaller version of the gardens of Versailles, but public. Crossed by Avinguda Diagonal, it could have gone ahead if the purchase of the land could have been agreed with Eusebi Güell and his heirs, the owners most affected by the project, but this wasn’t possible.

Finally, let’s imagine we make our way to the restaurant of the funicular railway at Sant Pere Màrtir, an eclectic 1918 work by Fèlix Cardellach and Tomàs Brull housed in a tower. As the train climbs, we can make out the entire course of the Diagonal, as well as the imposing Torre de Collserola communications tower, built 70 years later by Norman R. Foster, and the whole of Baix Llobregat. And finally, to rest, we’d take a tram from Plaça d’Espanya to the Ciutat del Repòs i les Vacances (City of Rest and Vacations) of the GATCPAC (Catalan Architects’ and Surveyors’ Group for Progress in Contemporary Architecture), a macro leisure and rest area designed in the 30s one street back from the seafront stretching from Gavà to Sitges.