If you ask anyone from Barcelona if they know about the city’s Museu Roca, the answer will be no. After the war, it faded into the shadows of an old warehouse on Paral·lel without a trace. It is only now that we are able to evoke the history of this anatomical and fair phenomena museum, which had been active during the 1920s and 30s.

© Historical Archive of the City of Barcelona

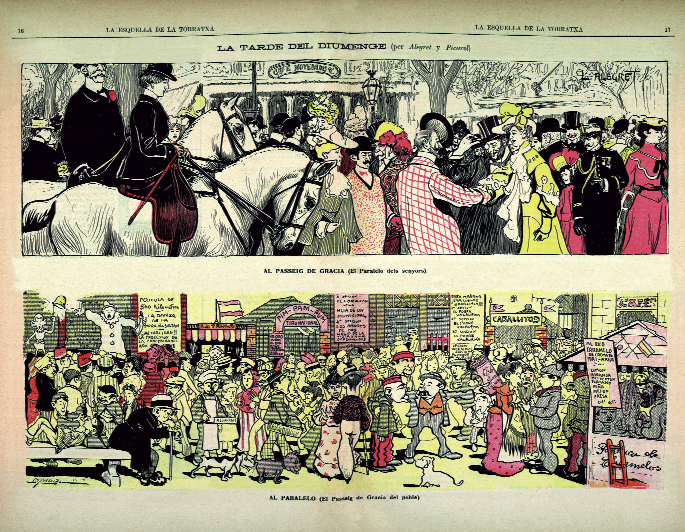

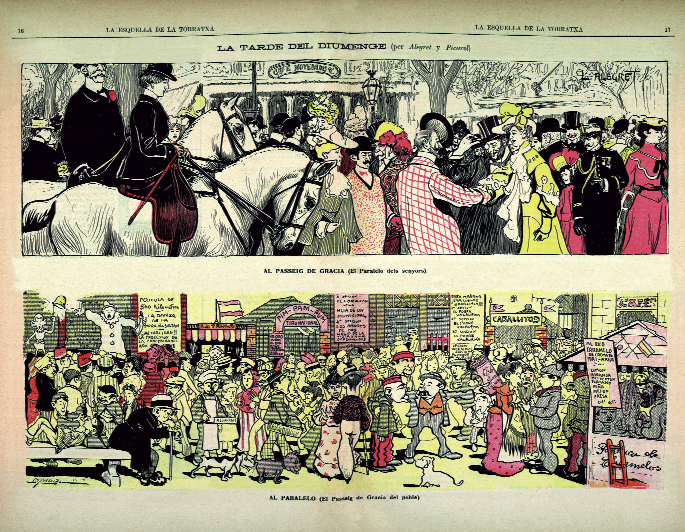

Drawings of Alegret and Picarol in L’Esquella de la Torratxa from 6 January 1905:

Sunday afternoon on the Passeig de Gràcia, defined as the “Paral·lel of the gentry”, and on Paral·lel, “the Passeig de Gràcia of the people”.

The Museu Roca is only the swansong of a strange and eccentric world that reached its heyday in mid-nineteenth-century Barcelona. It is now in Belgium. Let us then go back in time to recover it.

In 1854, the medieval walls of Barcelona were demolished and the predominantly rural-looking area that had separated these walls and the gardens of Sant Bertran, in the foothills of Montjuïc, became a new spill-over area for the streets of the Raval neighbourhood and a public space.

This place frequented by carriers, where criminals used to hide en route to the mountain and where camps of gypsies were erected, as described by Juli Vallmitjana in La Xava and Sota Montjuïc, was soon to become the favourite recreational haunt of the poorer classes. In 1892 the Circo Español Modelo (subsequently renamed the Circo Teatro Español) was built. It was erected next to Carrer Nou de la Rambla and immediately began to pull in myriad travelling fairs, shows and stall-type attractions that populated Paral·lel.

Until then these fair stalls had been set up in Plaça de Catalunya and Plaça del Portal de la Pau, acting as a nexus between the theatres and shows patronised by the middle class citizens of Passeig de Gràcia and La Rambla. Paral·lel afforded the opportunity to relocate shows that were more in tune with the working and poor classes in view of their penchant for more gruesome, melodramatic and eccentric attractions that mirrored a facet of reality that was closer to them. This ambience is described to us by Luis Cabañas1 in Biografía del Paralelo (Barcelona: 1945, pp. 19–21):

“It was abuzz with churro, peanut, orange and melon sellers, the ‘toasted chickpea guy’, and in summer ‘Chaumet’s ice creams’, in his whitewashed, spick and span cart: iced sweets! In the early days of that ‘Capernaum’ on Paral·lel […] it was brimming with tricksters extolling the virtues of the ‘marvellous ointment of the Pyrenean whale’, or the Lad from Tona, dentist and tooth-puller, Geraldine’s Elixir, in honour of the Beautiful Geraldine, who strutted her stuff on the trapeze of the Alegría Circus in Plaça de Catalunya, as full of stalls as the up-and-coming Paral·lel. We recall one trickster, the purveyor of a corn cure, as he poked at the picture of the inventor in question: ‘Here is the great North American expert who discovered this marvellous corn cure…’ The trickster continued to poke away at the poster and the great North American expert, the destroyer of corns and calluses, who was none other than the composer Rossini, with his large, sardonic and good-natured face.

“[…] Opposite El Español, still under construction, a circus was set up like a fair, assembled with cloths and boards by way of seating and acetylene light. The original thing was that the only worker was a lady who walked the tightrope, put some trained dogs through their paces and sang a French cuplé on a two-metre wide stage. She sang unaccompanied, not even by a piano, sporting a green suit with sequins.

“[…] Loud shouts announced the wares on sale at the stalls, or advertisements and notices were written on the blackboards, all in extremely grotesque taste. By way of example: ‘On sale for health reasons, a phenomenon: superb, elegant, very clean, tame and totally free. Perfect for family entertainment’. It was an old and ailing performing pig. Another ad read: ‘On exhibit: an ox with the head of a bulldog, the tail of a bear and the leg of a swine. Peaceful and tame, it is also a hermaphrodite’.

“The people were captivated by those stalls, illuminated by acetylene light. The director usually turned up in a greasy and darned frock coat and dented top hat, his legs crammed into drill trousers and sporting rope-soled sandals. The absurd sight of the ‘phenomena’ and picturesque acrobats were soon complemented by wax museums, palm readers, fortune tellers, occultists, astrologists and a very fat lady, Madame Sphinx, who foretold the future no matter how blurred it was.”

© Coolen Family Collection, Antwerp

Human child skeletons, an example of the exhibits included in anatomical museums. Drawn from the Museu Roca, they formed a part of the collection acquired in 1995 by the Belgian collector Leo Coolen at the Mercantic in Sant Cugat.

We have heard of this world, described by Luis Cabañas, but we find it hard to relate to it because it is enshrouded in a silverscreen-like halo – Freaks (1932) by Tod Browning springs to mind – at odds with reality, because we have never actually seen any graphic evidence. That world of bearded women, Siamese twins, strongmen, false mermaids, wax museums and anatomical museums exhibiting syphilitic sores and flaunting the human body with an unheard-of brazenness disappeared without trace in Barcelona, barring some satirical drawings by Picarol and Opisso. The newspapers contain the odd review, such as that of 8 March 1898 in El Diluvio, which placed the following attraction at number 19 in La Rambla de Santa Mònica, next to the Napoleon photography studio: “Danae. A staggering show, a phenomenon the likes of which has never been seen before, half-man with full beard and moustache, and half-woman.” But little else. They were regarded as vulgar spectacles that did not deserve to be mentioned in the press, a press which, on the other hand, did not target the poor classes because the vast majority of the working population was illiterate.

From Paral·lel to Belgium

But the story of this world, now hidden and forgotten, would take a strange turn. In 2010 we discovered an old bookseller who had a poster for the Museu Roca which, in a sideshow on Paral·lel, exhibited “in a real and educational way for the people” a collection of anatomical wax figures depicting the consequences of vice, prostitution and drugs. It was called “The Havoc of Chinatown”. The exhibition, advertised under the control of the Directorate General of Health, was accompanied by a freak show: “the monkey man”, “the giant spider of Japan”, “the Siamese sisters”, “human monsters”, “the freak gallery”, “real human foetuses” and so on.

More than 500 wax figures were advertised. A set-up of such dimensions made it even stranger to think that we had never heard of such a show.

On investigating the origin of the museum, we also encountered Alfons Zarzoso, a historian of science and director of the Museu d’Història de la Medicina de Catalunya, and Pepe Pardo, a lecturer and researcher at the Agencia Estatal Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC), who had learnt of it through similar channels. We discovered, to our surprise, that the collection of anatomical figures of the Museu Roca still existed, but that it was in the hands of a private collector in Antwerp, Belgium, named Leo Coolen, and that the collection had been exhibited twice, once at the Dr Guislain Museum in Ghent (“Kermis of Kennis”, Belgium, 2008) and at the Wellcome Collection in London (“Exquisite Bodies”, 2009).

It was a collection of anatomical studies, common and venereal diseases, pregnancy and childbirth, foetuses, skeletons, a collection of phenomena and monsters of nature (animal and human), medical instruments, torture devices and a guillotine, which was all part of a show like the one that Nicomedes Méndez, the executioner of Barcelona, had intended to set up in 1908 after his retirement, next to La Pajarera Catalana (which would become El Molino), and which was to be called the Palace of Executions, although he failed to secure the authorisation.

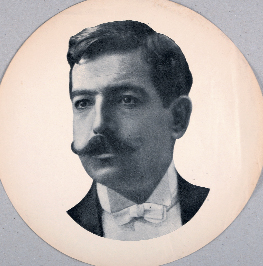

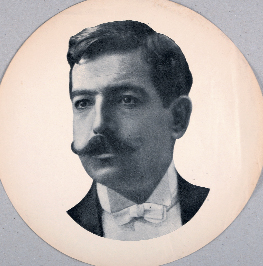

© Enric H. March Archive

Portrait of the magician and ventriloquist Francesc Roca.

Francesc Roca, magician and ventriloquist

The father of this “monster sideshow” was called Francesc Roca Guàrdia, who hailed from Tortosa. We do not know when he was born, but we do know that he died on 2 October 1945, thanks to the obituary published in Ilusionismo, the magazine of the journal of the Sociedad Española de Ilusionismo. He was a magician and ventriloquist. He belonged to the first generation of magicians that began to stage shows for the general public in the nineteenth century, like Fructuós Canonge and Joaquim Partagàs.

From the late nineteenth century and into the first half of the twentieth, Francesc Roca and his sons, Ernest and Alfons, staged magic shows that also featured ventriloquism, music, circus, robots and wax figures. His sons became magicians under the name of The Fak Hongs in the 1920s. Ernest was director of the Sala Mozart until the 1950s.

There are some records of their stage activities, but there is no mention of the anatomical and wax museum anywhere. The Roca family travelled the fairs with their sideshow, putting on all kinds of shows until the 1920s when they decided to settle in Paral·lel, and subsequently in Carrer Nou de la Rambla, where they built up a business around the anatomical museum and the distribution and showing of scientific films, which included images of operations and childbirth.2

We still know precious little about their business activity. After the war, Roca’s wax figures and all the material used by the family in its shows ended up in a warehouse on Paral·lel, probably a room in the Teatre Nou on the corner of Carrer Nou de la Rambla.

In 1987, this material surfaced during some work that was being done there and was bought by the antique dealers of the Casa Usher, who then sold it to Francesc Arellano, the owner of the Anamorphosis antique store in La Baixada de Santa Eulàlia. The performing arts pieces were acquired by the Institut del Teatre and the magic ones by the magician Xevi, who now has them on show at his house-museum in Santa Cristina d’Aro. But nobody wanted the anatomical collection, not even the public institutions of Catalonia and Barcelona.

Arellano exhibited the Museu Roca (1988–1995) in an apartment on Carrer de la Palla, where some students from the Escola Superior Universitària d’Imatge i Disseny produced a documentary as part of a course project, which can be seen on the internet to give an idea of the impression it caused.3 In 1995, Arellano took the collection to the Mercantic antique market in Sant Cugat with the intention of finding a final buyer, and there it was purchased by its current owner, Leo Coolen.4 A small part of ephemera (posters and sundry publicity) remained in Barcelona and has been preserved, as have the photographs taken when the collection was discovered.

Some twenty museums and collections

The first question that comes to mind is how and why the Museu Roca actually came to be; why bodies and diseases were turned into a show. It is not a one-off phenomenon. It was part of a process that unfolded over 100 years, from the mid-nineteenth century (although its forerunners date back to a few centuries before that), and took place throughout Europe and America.

Research into the Museu Roca has allowed us to document some twenty museums and anatomical collections in Barcelona between 1849 and 1938. They emerged as a natural continuation of the traditional wax museums, showing biblical and historical scenes and eventually adding anthropological and natural science-related items, in the image of the old cabinets of wonders. They were private collections of bizarre and exotic elements that, since the 1500s with the beginning of the great colonisations, had stirred the curiosity of nobles and bourgeoisie alike.

In the 1800s the general interest in science and the emergence of universal exhibitions took private collections to a non-specialised audience. Some of them would spawn the first public museums, while others were to become travelling shows or attractions. Public exhibition and the body as a spectacle were often paired with both medical anatomy and anthropology, where there was room for live beings, natives from the colonies, exposed to the curiosity of the white man in museums and human zoos, which also existed in Barcelona. In 1897, on some open ground in the Ronda de la Universitat next to Plaça de Catalunya, an Ashanti tribe from Ghana was exhibited; in 1913, a “Mohammedan” tribe in the Turó Park and a Senegalese tribe in Tibidabo; in 1915, the tribe of “The Himalayas” in the Turó Park, advertised in La Vanguardia as “the most bizarre phenomena in the world, neither men nor monkeys”, and the Lilliputian Village, an “original reproduction of a settlement, with its streets, houses, church, etc., and its tiny inhabitants”, as advertised in La Vanguardia (July 1917).

With some exceptions, the anatomical museums of nineteenth-century Barcelona are located in the city centre, and in well-prepared theatres or premises. The collections arrived after visiting Europe and America; they came from places such as Paris, Stockholm, Switzerland or the United States, and were endorsed by the scientific community, hygiene campaigns and public success. The collections targeted a bourgeois public, what the reporters of the time called “an intelligent audience” to avoid confusion with pornography, as had occurred in London and the United States. Moreover they were often intended only for a male audience, an unequivocal sign of the nature of their content.

Maybe it is difficult for us to see anything in those figures that might arouse our curiosity and libido, but we need to imagine ourselves in an era with a way of thinking in which showing the inside of the body was a taboo. Not to mention the fact that the figures are displayed nude. Human anatomy, physiological processes and diseases are exhibited, but nudity will inevitably draw our attention. One of the most admired pieces of these exhibitions, for example, was the anatomical Venuses. Seeing them can give us an idea of the impact they might have had on the general public in the nineteenth century.

Deployment: 1849–1892

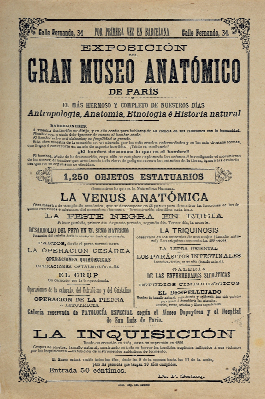

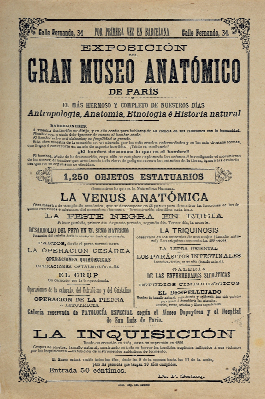

© Enric H. March Archive

Advertisement for an exhibition of the Great Anatomical Museum of Paris on Carrer Ferran in Barcelona, in 1886.

By way of an inventory, we can take a look at the collections and museums documented hitherto in Barcelona, with some brief commentaries that allow us to identify their nature. There were almost certainly more of them: the research has not yet concluded. We will begin with the period from 1849 to 1892, the year the Circo Español Modelo was opened on Paral·lel.

—1849. Museo del Doctor Soler, Carrer de Sant Llàtzer. A cabinet of curiosities with a collection of anatomical wax figures made by Chiapi, who also did some of the figures in the anatomical collection of the Facultat de Cirurgia i Medicina (1843).

—1866. Gabinete Anatómico, Carrer de Raurich. From the United States. Eight hundred exhibits. According to El Principado: “An anatomical cabinet has been opened on Carrer de Raurich which contains more than 800 anatomical specimens of different phenomena of the human body, many of them of real-life size, for the study and practice of anatomy and practical surgery and other different ones that deserve to be seen by intelligent people.” And also: “There is a particularly striking hydrocephalus, and a rich exhibition of foetuses from the embryo stage through to full development.”

—1867. Natural History, Carrer de Quintana 12, 1r. A store for the sale and exhibition of natural science material, with skeletons, phrenology and anatomical models in wax.

—1868. Museo Anatómico, Antropológico y Etnológico, Rambla de Canaletes. 15,800 exhibits. “Following numerous petitions to the museum director, an extraordinary session will be arranged for the ladies” (El Principado).

—1875–1876. Museo Alejandro Hartkopff. Salón Teatro del Circo Barcelonés, Carrer de Montserrat, 18–20. From Paris and Stockholm.

—1876. Gran Museo de Figuras de Cera. Teatre Romea, Hospital 51. Reserved cabinet.

—1876–1877. Gran Museo de Figuras de Cera. Rambla de Santa Mònica 2, next to the Teatre Principal. Reserved cabinet.

—1878. Museo Anatómico de Figuras de Cera. Teatre Tívoli, Carrer de Casp, 8. “Next Sunday will see the grand opening of the great anatomical museum with wax figures that are being prepared in the Tívoli, with the attendance of the authorities and the press and other people who will be subject to incitement [sic].” (La Imprenta).

—1885. Museo Anatómico O. Thiele. Plaça de Catalunya, in a stand next to the Circo Ecuestre.

—1885. Gran Museo de Figuras de Cera. Historical and Anatomical. Carrer de l’Hospital, 101. “Unique. The best and largest travelling museum in Europe, new in this capital” (La Vanguardia).

—1886. Gran Museo Anatómico de París, by Dr F. Sestacq. Carrer de Ferran, 34. With an anatomical Venus and a gallery of syphilitic diseases. “Reserved Special Pathology Gallery according to the Dupuytren Museum.”

—1887–1889. Casa Darder, Jaume I, 11. Gabinete de Historia Natural, Mendizabal 19. Darder Museum, Via Diagonal 125 (Gràcia). Francesc Darder Museum-Shop.

News about these exhibitions was published in the city’s newspapers which provided enthusiastic accounts. They were also advertised in the shows section among theatrical events. It was, however, a place for the learned because, apart from the Teatre Odeon, which hosted popular melodramas, the theatres in the city were frequented by an artisan and bourgeois audience.

Neither should we forget that in addition to these temporary collections open to the public, the then Facultat de Cirurgia i Medicina (1843) had an anatomical museum devoted to the teaching of medicine, located at its headquarters in Carrer del Carme in the former Hospital de la Santa Creu. The faculty’s anatomical collection came from the Cabinet of Anatomical Specimens of the Reial Col·legi de Cirurgia de Barcelona, started at the end of the eighteenth century. It remained there until the faculty and museum were transferred to the new Hospital Clínic in 1906. Neglected and derelict with the passage of time, abandoned and badly damaged, it was recovered and restored and since 1981 has been part of the Museu d’Història de la Medicina de Catalunya in Terrassa. The old Hospital de la Santa Creu still houses the Reial Acadèmia de Medicina and the magnificent eighteenth-century anatomical amphitheatre.

Following Paral·lel’s boom as a haunt for popular leisure, the anatomical and wax figure museums began to disappear from the city’s downtown area. This relocation process was normally accompanied by the disappearance of these collections from the news items in the press. As was mentioned above, the attractions on Paral·lel were deemed vulgar, and the anatomical museums were connoted and excluded when they began to occupy the same areas as the places that were associated with vice and prostitution.

—1896. Museo Histórico y Anatómico de Figuras de Cera. Paral·lel 80, on the corner of Ronda de Sant Pau.

—1900. Museo Anatómico. Parallel, 63–65. Documented in a drawing by Opisso.

—1915. Museo Anatómico de Figuras de Cera, for sale. Carrer de Sant Pau, 111.

—1922. Exposición Anatómica, from Carrer de Sant Pau, 10. Carrer Nou de la Rambla, 58.

—1922 (May). Museo Anatómico d’Enrique Crespo. Carrer de Sant Pau, 10. “On the 16th of this month, the Anatomical Museum located at Carrer de San Pablo, 10 was officially opened. The opening ceremony was attended by numerous people as well as several medical celebrities who, like the other people in attendance, had nothing but praise for the Museum. Mr Enrique Crespo, owner of the museum, received many and richly-deserved congratulations” (La Vanguardia).

—1927. Museo Anatómico. Carrer de la Unió, 9.

—1930 Museo Anatómico. Carrer Nou de la Rambla, 44. Notice of sale of an anatomical museum, vaults and attractions.

—1937–1938. Museo Anatómico de la Cruz Roja, by Ramón Catalán (Boletín de la Cruz Roja, March 1938). Carrer Nou de la Rambla, 22. “To benefit general needs and those of Red Cross Hospitals at the front and rearguard: today, Sunday, at three o’clock this afternoon, an Anatomical Museum will be opened on Carrer Nou de la Rambla, 22. The profusion of figures, the sensation of reality that they give, the interest of the subject matter and the excellent facilities are all a guarantee of success and with it a stream of economic revenue that will help to bear the heavy costs incurred by such a humanitarian institution” (La Vanguardia, June 1937).

In 1944, an advertisement in La Vanguardia reported that “an anatomical museum for fair stallholders” was up for sale at Ronda de la Universitat, 44. This is the last news that we have of this kind of exhibition in Barcelona. The war, changing mindsets and the repression of the dictatorship are the factors that led to the disappearance of the anatomical museums, which does not mean that they did not survive in travelling fairs.

© Theatre Institute Performing Arts Museum

The makeshift theatre where Francesc Roca performed his shows.

The open history of the Museu Roca

The Roca collection saw the light in this popular recreational setting. After it was exhibited on Paral·lel between dates that we cannot exactly specify, but which would fall somewhere between the 1920s and the 1930s, it finally settled in Carrer Nou de la Rambla, 25. Despite the magnitude of the attraction and Roca’s interest in publicising it, there is no news of it in the press.

However we do have the advertising material generated by Francesc Roca, where the emphasis is placed on the scientific aspect of the exhibition, purporting to enjoy the support of the Red Cross. The excuse was the fight against venereal diseases that had been rampant since the late nineteenth century. But what is suspicious is that the material published advertises the remedies that were sold during the exhibition, and of which he was the representative. Roca was acting as a shyster. The museum is the bait, a very effective lure that appeals to people’s base instincts. No matter how much the educational aspect was emphasised, syphilis and its sores concealed an element that never fails: sex. And this is what the punter sees: not the consequences of the act, but the act itself. This imagination is boosted by the sensual anatomical Venus and the exhibition of genitals and other attention-grabbing phenomena, such as hermaphrodites.

The history of the Museu Roca is full of shadows, mysteries and questions regarding its origin and impact on the locals. Nevertheless, we are convinced that future research will throw up some new information. Its emergence has allowed us to enter a hitherto unknown world and discover that Barcelona had a long-standing tradition of anatomical museums spanning almost a century. Only some documentary traces of these collections remain: press reports, some posters and two non-illustrated catalogues. On the other hand, the only material proof that remains, the Roca collection, is far from Barcelona.

Anatomical museums were a major spectacle for the masses, but their own “vulgarity” wiped them from the map. The history of Paral·lel, as we saw in the exhibition Paral·lel 1894–1936 (Barcelona Contemporary Culture Centre, 2012–2013), is full of omissions. We can debate the suitability of the use of the material on display, but there is no doubt that the anatomical museums, particularly the Museu Roca, make up a story that explains how science was used by laypeople, occupying recreational spaces that in principle are not the realms of science. It is both a history of how mindsets change and how we hide what we dislike about ourselves.

The Museu Roca is now in Antwerp. It might be worth bringing it temporarily to Barcelona and rebuilding that world which fascinated our ancestors. A strange world where curiosity and the representation of reality turned the human body into a spectacle. It is not a question of reviving the curiosity of those fair attractions with human phenomena and zoos, but rather of reconstructing a time and ways that have led us, without our realising, to where we are now. The evolution of the human being is forged by all that we gain as well as all that we leave behind.

Notes

- Pseudonym of Rafel Moragas, Moraguetes, and Màrius Aguilar.

- See Enric H. March, Francesc Roca i el cinema: ‘Los averiados’ (1933) [online], in Bereshit (http://dom.cat/9f6); Enric H. March, Francesc Roca i el cinema: ‘Como venimos al mundo’ (1934) [online], in Bereshit (http://dom.cat/9f5).

- Estragos del Barrio Chino, on YouTube.

- The L. Coolen Roca Collection, on YouTube.

La ciutat trasbalsada. Barcelona 1901 -1910 (The upset city. Barcelona 1901-1910)

La ciutat trasbalsada. Barcelona 1901 -1910 (The upset city. Barcelona 1901-1910)